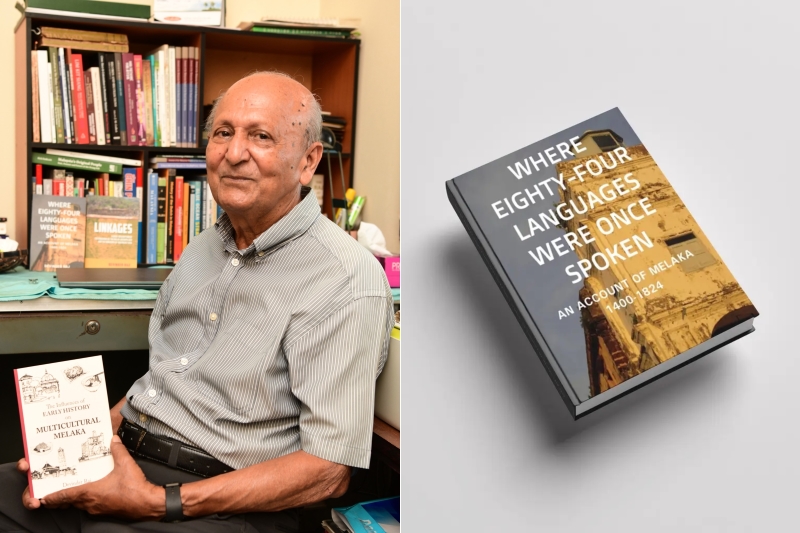

Devinder emphasises that if he writes something controversial, he backs it up with references, be it by British or local authors (Photo: Patrick Goh/ The Edge Malaysia)

“Let’s go to Kedah,” a friend suggested to Devinder Raj when he was teaching in Kota Bharu in the 1960s. He went, he saw and he was captivated by the ancient ruins of Bujang Valley. Later, during visits to Indonesia and other parts of the region, he noticed more of such structures with similarities, and what Carl Sagan said about having to know the past to understand the present hit home.

Devinder beheld remnants of Hindu temples at archaeological sites in Bujang Valley; Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, Cambodia; Borobudur in Central Java, Indonesia; Laos and Vietnam. He learnt “many of the ancient ruins had links with the Malay Kingdom”.

Intrigued, he set out to trace the connections, leading to a deeper interest in the past. “After I retired, I said, ‘Let me look at writing something about history.’ Before that, the only history I did was in Form Six.” He then wrote three books in quick succession during the Covid-19 years.

Where Eighty-Four Languages Were Once Spoken: An Account of Melaka 1400–1824 (2020); The Influences of Early History on Multicultural Melaka (2021); and Linkages: A Brief Description of the Kingdoms of the Malay Archipelago and the Kingdoms of Southeast Asia (2022) were released under Gerakbudaya.

A fourth title by the same publisher, The Imperial Agenda: The British in Malaya from 1786 to 1957, is expected to be out by end-March. It examines their quest to control the peninsula.

Much of what has been written about that period is British-biased. In the last 15 to 20 years, Malaysian and other writers have presented a “slightly different viewpoint about colonial rule here”. On the agenda was the employment of ‘Gun-boat Diplomacy’, which involved using naval strength and military intimidation to secure strategic locations such as Penang, Singapore and Pangkor Island. “The Pangkor Treaty was signed on a gun-boat in 1874 and there was much pressure on the Malay royalty to sign,” he says.

Tracing the facts has widened Devinder’s perspective on Sagan’s famed statement, and he thinks “people in politics should know about the background of the country: the processes it went through in the early years to comprehend why certain things are done a certain way”.

linkages_a_brief_description_of_the_kingdoms_of_the_malay_archipelago_and_the_kingdoms_of_southeast_asia.jpg

In Linkages, he quotes the renowned French scholar of the history and archaeology of Southeast Asia, George Coedés: “From Indianisation was born a series of kingdoms that in the beginning were true Indian states: Cambodia, Champa and the small states of the Malay Peninsula; the kingdoms of Sumatra, Java, and Bali; and, finally, Burmese and Thai kingdoms, which received Indian culture from the Mons and Khmers.”

There is no exact record of when Indian sailors first reached the Malay kingdoms for commerce, though there are references to them in Indian fables and holy texts, the author adds. Artefacts found in Bujang Valley date back 2,000 years, compared to written records on Melaka, which was founded around 1400 — a time some historians claim the country’s history started from Kedah as it had the earliest civilisation in the Malay Peninsula.

Segamat, Johor-born Devinder, who moved from Mantin, Negeri Sembilan, to Kuala Lumpur more than 20 years ago, begins his history journey from Melaka, where he grew up near the foothills of Gunung Ledang. Like the early travellers who followed the wind and sailed where opportunity beckoned, work took him to different countries where he picked up a smattering of languages and quietly fit in among strangers.

“My father migrated here, so travel is in the blood,” says the Universiti Malaya graduate who taught at a Chinese school in Kota Bharu and was a language officer with the Ministry of Education before joining the British Council. When asked if he was willing to be head of English at the Beijing INTI Management College, he replied, “Yes, why not?” His two years there were a welcome chance to brush up on his Mandarin, having majored in Chinese studies in the 1970s.

With nothing much to do after returning from Beijing, he said yes again when Yayasan Salam Malaysia needed a volunteer to teach in Laos. He was attached to the National Ministry of Laos and did training programmes for pre-ed teachers.

Laos in 2002–2003 was undeveloped and the people were very slow in doing things. Its acronym was Lao PDR (People’s Democratic Republic), “but generally foreigners said, ‘Laos, please don’t rush.’ Things really moved slowly and there were no proper main roads. There was dust everywhere on the laterite roads, but the country was interesting.”

devinder_raj_books_melaka.jpg

Beijing between 1999 and 2000 was under Deng Xiaoping and rushing to modernise. Devinder recalls being based on the outskirts of the city, near the last stop of a rail service. The INTI college had two separate blocks and no lifts, and he had to walk up and down six floors for both. “That really kept me fit.”

With his three children grown up, he does not wish to twiddle his thumbs. Writing has kept him occupied, although starting took some time. “I wrote my autobiography — it was meant for family and friends — and that gave me the impetus: If I can do this, I could write something else.”

Devinder uses a lot of references from both British and local writers in his books. “If I want to say something controversial, I back it up by quoting whoever made the statement, then add my comments. I try to look for alternative viewpoints from different authors. If you want to write, you have to read, especially history.”

There is reason to shed light on what happened before, which impacts the now, even if most people may not be keen to know.

The British brought in a lot of convicts from India to the Straits Settlements of Penang, Melaka and Singapore, he shares. They were used as labour to develop infrastructure, especially in Singapore. “Many of them were not criminals. I read that convicts from Malaya were sent to India and Burma. It was the British way of dealing with those who opposed them — send them away.

“The other thing not many people know is opium was a huge trade then. At one time, revenue from it was much more than that from rubber and tin. The British obtained opium from India and farmed it out to the local Chinese businessmen to manage. They didn’t deal with it; they just collected the taxes and revenue.

“If you look at the history, most of the early Chinese millionaires got their revenue from opium because they had a monopoly on it. Very little has been written about this. It’s an area I’m looking at as I think people will be interested in reading about it.”

the_imperial_agenda_the_british_in_malaya_from_1786_to_1957.jpg

When the British were here, the Chinese were recruited to work in the tin mines. Some of the latter started their own business in towns, Devinder continues. The Indians mainly provided the labour on the plantations, while the Malays were paddy farmers. “There wasn’t integration of the races in the early days. We had a plural society, not an integrated one. And it’s become more plural now.”

On the positive side, missionaries brought education to Malaya and started Tamil and Chinese schools. It was a good thing, even if the intention was to get converts, he adds.Also, administrative policies and the growth of industries, plantations and infrastructure proved advantageous for Malaya.

Devinder, who used to read spy novels and science fiction but hardly has time for them now, thinks historical novels can make the past interesting and bring parts of it to readers. But he reckons he lacks the flair for such writing as “you need to twist and turn the story and have lots of ideas”.

Then again, life is hardly straightforward. “I am Northern Indian and there was only one other Sikh family when my father was working in the plantations. In primary school, I went to a boarding house in Melaka. That was my first experience. Luckily, I was there with my brother, who was a year older. My classmates were all strangers to me. Most of them were Tamils, so I picked up the language.

“I suppose you get used to it, studying with Chinese, Indians, Malays, the Portuguese and the Dutch. It was the same at Malacca High School, there was a very mixed group. I had no problems. Melaka, even today, is quite cosmopolitan, more so than other places, except maybe Singapore and Penang.”

Looking beyond the state, Devinder says there were lots of Indonesians in the country in those days. Also, people from Sumatra used to send their children to Penang to study because there has been a trade link across the Strait since a long time ago.

With these diverse, connections, this 83-year-old author who speaks various languages might just be inspired to write something that surprises even himself.

Purchase 'The Imperial Agenda: The British in Malaysia from 1786 to 1957' at RM55 from Gerakbudaya here.

This article first appeared on Mar 11, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.