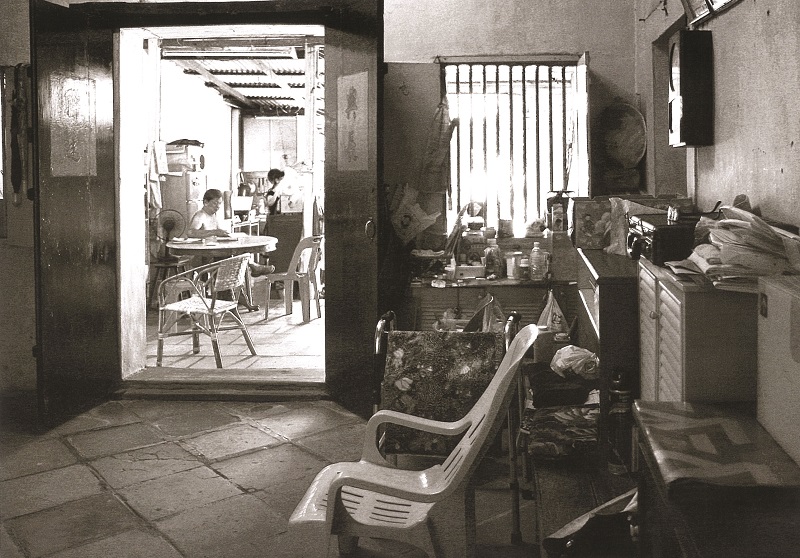

Phillips new movie aims to preserve Kampong China's cultural heritage (Photo: Jennifer Phillips)

Inspired by what Rosita Abdullah Lau has done to preserve the Terengganu Peranakan heritage in Kampong China, a young filmmaker whose mother is a Penang Nyonya now living in Singapore has reached out to lend a hand through reel.

Jennifer Phillips, who owns independent film production company Castles In The Air Pictures, is putting together a documentary based on Waterfront Heirlooms: Reflections of the Kampong China Peranakan, called The Last 800 Metres. The idea for that was spawned after she was introduced to Rosita by May Chua and Sylvia Tan, who designed the book.

jp_11.jpg

“There is so much in the book. I told Rosita that if you want the world to know about a cultural heritage, you need to deliver it in a concise form,” says Phillips, who works from the US, Canada and Singapore. She then suggested shooting a 90-minute feature to tell the Kampong China story. Work has begun and she hopes to complete it by November next year, in time for submission to the 2021 Cannes Film Festival.

“If we are lucky enough to get a screening there, we will probably submit the documentary to major film fests. Getting the work out will make people realise that the Terengganu Chinese Peranakan culture exists in this part of the world. There are a lot of indigenous cultures in the big cities and everybody associates Peranakan with Penang and Singapore.”

Phillips made her directorial debut in 2017 with Blood Child, a horror fantasy inspired by local myths of kui kia (the ghost child in Hokkien), which reportedly made waves on the festival circuit last year.

“My mother is Peranakan, which is why I could understand the Hokkien [words in Rosita’s book]. I’m one of the last few from my generation who speak it the same way [as the Penang Hokkiens],” says Phillips, whose father is British and vividly remembers visiting her maternal grandfather’s house in Ji Tiau Lor Buay (Noordin Street, George Town). “It’s not just the food; the language is disappearing as well.”

The challenge of producing a documentary on Kampong China is compounded by a lack of archival footage on the village and how its people lived, worked or played. The many photographs in the book are handy, but Phillips hopes those with videos or film footage will step forward and share what they have for The Last 800 Metres, a project that seems like a race against time, considering that a couple of people interviewed in Waterfront Heirlooms have passed on during the eight years that Rosita worked on it.

She is desperately looking for a music composer and someone to write Hokkien songs for the documentary. “This is very meaningful. It’s culture. If done correctly, it can be also be entertaining.”

pg1031.jpg

Among the other guests at the book launch — many dressed in intricately embroidered kebaya tops — was Dr David Neo, a creative scholar at Universiti Teknologi Mara’s faculty of film, theatre and animation. He says there are basically nine Peranakan communities scattered around Malaysia, among them the Straits Chinese in Penang, Melaka and Singapore, the Chitty, Kristang and Dutch Eurasians in Melaka, the Penang Serani, the Kelantan Peranakan, and the Chinese Peranakan in Kampong China and Kampung Tiruk, both in Terengganu.

In February, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia’s Institute of Ethnic Studies was awarded a Unesco chair on social practices in intercultural communication and social cohesion. Neo sees the greater vision as getting the cultures and other aspects of Malaysian ethnicities and diversities recognised as well. As one familiar with Peranakan culture, he is committed to archiving what the country had in the last 200 years so the younger generation will have access to the rich heritage, which can also be showcased to the world.

Neo ([email protected]) and Phillips (j[email protected]) hope to hear from readers who can help them in their endeavours.

This article first appeared on July 22, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.