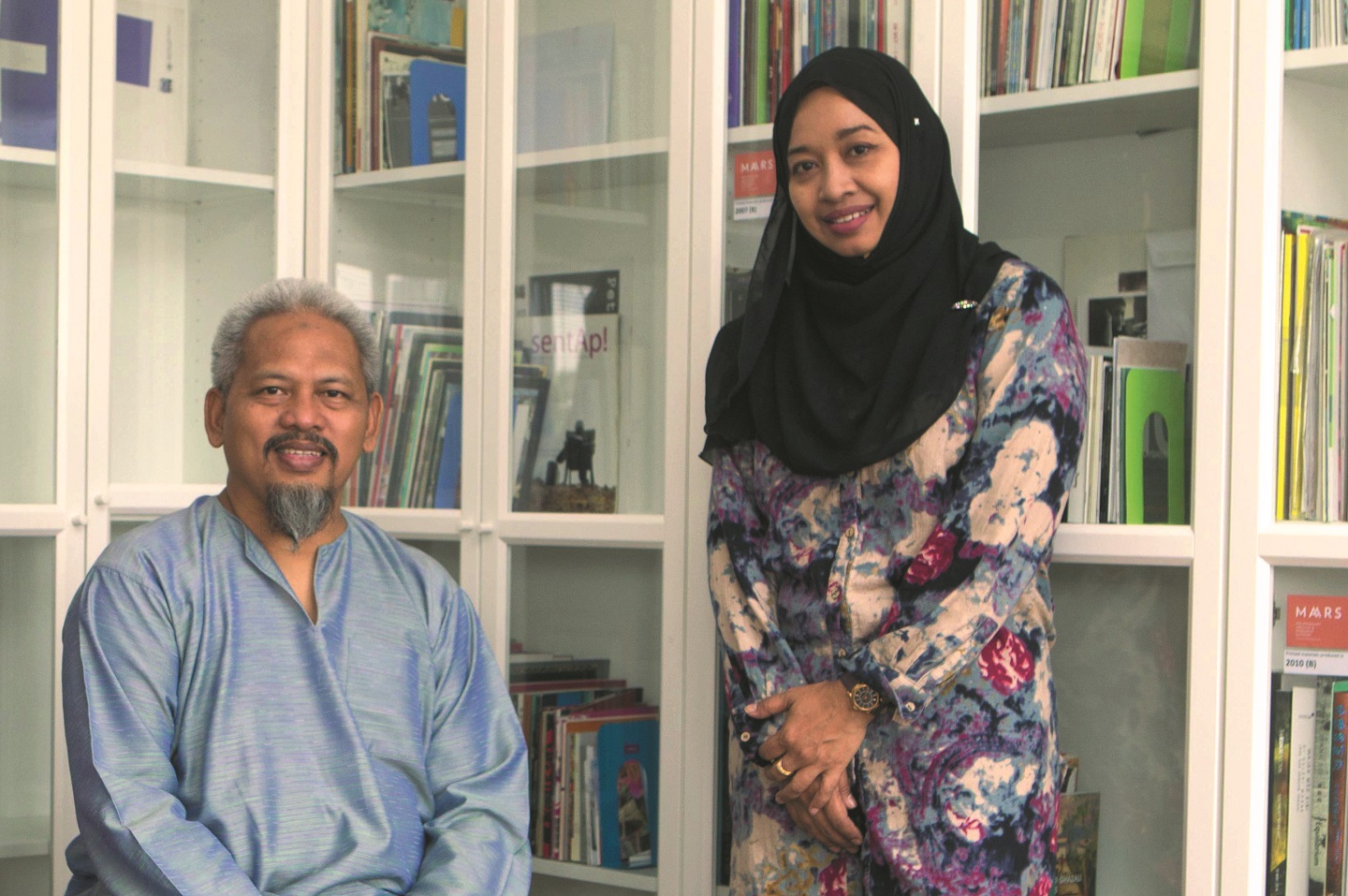

Artist and gallerist Bayu Utomo Radjikin; and Ipoh-based curator and art writer Nur Hanim Khairuddin

In an unassuming shoplot in Ampang is Malaysian Art Archive & Research Support (MAARS), in a cosy new home that it can call its own, after sharing a space in the nearby HOM Art Trans gallery for the last few years. Consisting of only book cabinets for now, it holds a comprehensive collection of materials on Malaysian visual arts. That said, the still empty slots reflect the work that lies ahead, but are also a reminder that laying the foundations for MAARS has been a slow but steady journey over the last five years.

The driving forces behind the initiative are database management specialist Shahnim Safian; well-known artist and gallerist Bayu Utomo Radjikin; and Ipoh-based curator and art writer Nur Hanim Khairuddin, who was inspired to start the initiative due to her own frustrating experiences in accessing materials for her work. Bayu and Hanim say that they have only just arrived at the starting point of what they want to do.

So, what does MAARS collect? “Our effort is fixed on any material related to Malaysian art, whether it is done abroad by local artists or related to Malaysian content. Alternatively, it can also be foreign artists who have done something here in Malaysia, say, with local galleries. So, it works both ways, but the most important function is to preserve Malaysian visual art content before it disappears, to be a one-stop centre,” says Hanim.

Anchoring that are the printed materials — essays, catalogues, ledgers, books and even artists’ notes. Then there is the audio-visual archive of local art events, such as exhibitions, book launches, talks and seminars, where videographers are sought on a voluntary basis or hired to attend and document them.

“For the first few years, we were busy establishing our name, slowly creating relationships with commercial galleries and making other contacts,” says Hanim. Bayu adds, “The hardest part is looming, we have yet to begin to scale it. Because collecting materials is one thing, but to digest, process and then digitise them, that is the hardest. It is a long-term process.”

The team is still exploring what key areas of information they can pick and choose to extract and perhaps add value to, or how to organise it.

“That is why we have to engage with researchers and curators to find an anchoring connection point, to determine what to focus on that will benefit them before we proceed,” Hanim says, adding that it is part of the reason why MAARS organises talks and dialogues with various people within the industry, which allows them to glean more knowledge, look at different viewpoints, and to enrich their existing materials. The public is welcome to attend these sessions.

The team also has another ambitious project in their sights — to send appointed curators to interview senior Malaysian artists on video. “It is what we call a roll video, where we sit with the artist and talk at length about all angles of their work and their lives. The point is to try to get material that has never been documented, heard or written about the artist. It goes beyond just their artworks, but spotlights the artist,” explains Bayu. The videos would also offer vignettes of the different eras or arcs of Malaysian art.

It may be a case of a plentiful harvest but MAARS’ resources are limited. The initiative has only one permanent staff member and works with a small budget, which is fundraised via an annual art exhibition with half the proceeds going to MAARS and the other half back to the artists. This year, a group exhibition featuring 33 artists, tentatively titled Three by Three, will be held this month.

To date, MAARS has in its collection over 3,000 printed materials ranging from the early days of Malaysian art in the 1950s to today, and over 500 audio-visual recordings from the last five years. However, it does not always have control over the speed of the collecting process. Hanim says, “We depend a lot on donations, as in materials. Even materials not suited for our archives we gladly accept and keep in our library section, where the public can come and browse anytime.”

In many ways, it is a waiting game, say the co-founders. “We have approached some individuals who are willing to donate their collections of materials. But it takes time,” says Bayu. One of them is the wife of the respected “father of digital art”, Ismail Zain, who has agreed to donate the late artist’s personal materials and notes.

“We may also come across certain books or materials in passing, but they elude us, as we do not know where to get them or who holds them, even if we are aware of their existence. This is particularly so with materials from the earlier years, such as the 1950s or 1960s. That is the major challenge,” Bayu says.

Describing the current Malaysian visual arts landscape as vibrant, the team has witnessed local art events grow from a handful to 20 to 25 per month — exhibitions, art talks and more.

“We started MAARS because we realised that archiving is important. Yes, it is normally done by the institutions, but we are not doing it because they aren’t. We just wanted to compile what we have. Even if there is another archiving initiative in town, that is good. We are not here to compete,” says Bayu.

MAARS welcomes donations of visual arts materials or volunteers. For more details, see here. This article first appeared on Aug 27, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.