The Macallan’s visitor centre and distillery are a subtle blend of theatre and hi-tech ingenuity (Photo: The Macallan)

Contrary to popular belief, equating a building with a villain’s lair can be a compliment. An agent of fine taste would agree: He goes by the name James, but people usually call him Bond. British architecture firm Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners designed a £140 million distillery for The Macallan, whose Scottish roots are inextricably intertwined with the longstanding spy franchise. Except, this cathedral of theatrics and understated glamour (perfect as a base for orchestrating dastardly deeds, just saying) aspires to extend beyond the brand’s image as 007’s choice of whisky and a pop-culture reference.

If only all headquarters of a nefarious baddie smelled like a sweet, hot bouquet of fermenting barley. Whiffs of alcohol swirled around the visitor centre, a rhapsody of flowing structure perched on a natural sloping contour that mimics the rolling hills of Speyside’s delicate countryside. Its centrepiece — a rippling roof constructed from 2,500 individual sheets of Scandinavian spruce slot together seamlessly like a jigsaw without nails or glue — is punctuated with pockets of light to clarify the atmosphere indoors where history is being made. Trees around the 485-acre estate are also conscripted as pleasantly porous barriers.

the_macallan2.jpg

When the air is biting, few pleasures compare with sipping on a Macallan Sherry Oak 18 Years Old to warm the body and gawking at a floor-to-ceiling glass wall housing nearly 800 vintage bottles dating back two centuries. A circular flight of stairs leads you to the bar, where you can sample some of the rarest single malts overlooking the Highland landscape and iconic Easter Elchies House, spiritual home of the brand since 1824. Your lesson in libations continues at the open concept-style distillery where interactive displays on turntables and West End-worthy visual projections impart knowledge on oaks, wash stills and ageing. Make sure to linger in the Cave Priveé — an underground sanctum decked out like a weapons galore that is private enough for a tutored tasting and modish enough to live out your espionage dreams.

The Macallan founder Alexander Reid, a barley farmer and school teacher, would not recognise Easter Elchies manor today, especially with two sporty Bentleys flanking it. Honouring the carmaker’s partnership with the distillery to further their green ambitions, a Bentayga Hybrid chauffeurs you through the estate, past the abundance of wildlife and 100-acre barley field, to the life source that started it all: River Spey. It was the sparkling stream’s vibrant blue and strength of the Atlantic salmon jumping on pristine water that spawned the idea for Macallan Edition No 6, which you can enjoy as part of a picnic experience. The malt with rich brass colour fills the nostrils with nutmeg, toffee and fragrance of an orchard in summer, leaving behind whispers of plum, sweet orange and spice on the palate.

macallan_inside.jpg

An architecturally rejuvenated Macallan is now seen as a flag-bearer of innovation, bringing modernity to a bracing drink described as the distilled essence of Scotland. A drawback to this slightest shift of emphasis, however, is that an overly austere and tech-reliant edifice could lose the human element so integral in the craftsmanship of whisky. The distillery is a romantic paean to the future, but only if up-and-coming custodians are mindful of its purpose to underscore, rather than distract from, the brand’s enduring legacy.

A clear sky in June also prompted another outdoor expedition nearby. Getting to the springs on Brauchill Hills was a long trek as it involved crossing meadows and a jumble of narrow paths speckled with prickly gorse. Carpets of these yellow wildflowers emerged from their lull in the botanical calendar, contrasting a saturnine landscape and perfuming our every step with a heady aroma of coconut and vanilla that makes wonderful flavouring for wine. It was a small crevice on a slope that led us to the uisge beatha, or water of life in Gaelic, that flows through the land and trickles past The Glenrothes’ distillery. All it took was an unadulterated sip from the ground, and then a glance at the cinnamon-y 12-year-old sloshing in our whisky glass to find out why most distillers have bunched together in this fertile locale.

glenrothes_whisky_wy_pic.jpg

Curious drinkers usually start their journey in the Rothes House, an old manse so inconspicuous there is nary a signboard. Previously the property of the community church, the stone house with a glassed-up patio was restored by Berry Bros & Rudd (former proprietors of The Glenrothes single malt brand, who sold it back to distillery owner Edrington Group) as their family getaway and an impromptu welcome area to host luncheons. There, you put on your wellies with knee-high socks tucked in before walking through a wooded path to the distillery just down the hill. What greets you before the 1879 building founded by James Stuart is not a fancy fleet of automobiles but a peaceful cemetery where villagers of Rothes, who once worked in the mills and warehouses, were laid to rest.

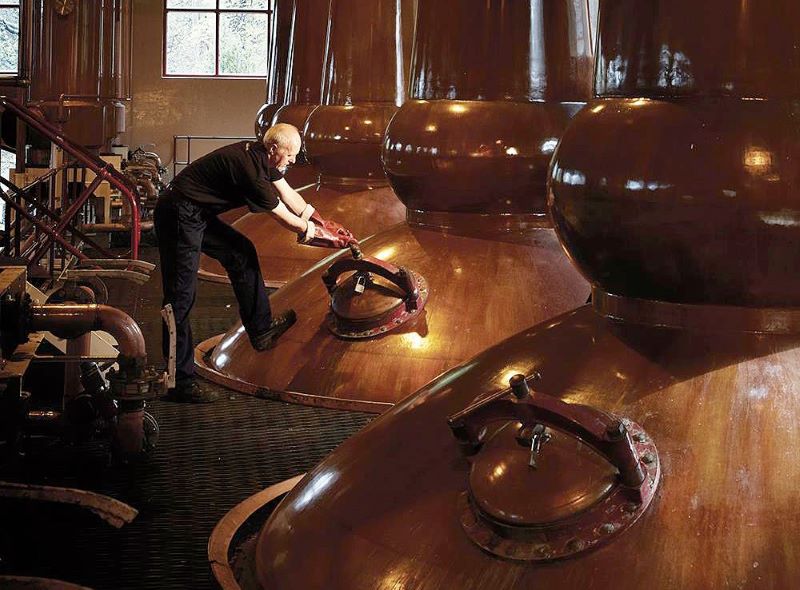

The Glenrothes distillery is not open to the public, with no visitor centre nor gift shop to accommodate travellers, but it is possible to score a private tour on slower days. Once inside, you will see procedures that have scarcely changed in centuries being practised, and craftsmen speaking earnestly about how a turbulent financial crisis urged a local reverend named William Sharp to raise funds and save everyone’s livelihood that hinged on the time-honoured art of whisky-making. The processes, from the muddy mash being raked to the way wort froths and seethes, are fairly standard. Like a broody teenager, these pots internalise everything, but people have time and time again hovered in front of them because they seemed lifelike and bursting with potential.

glenrothes_extra.jpg

The desire to achieve greatness in a scotch often means sussing out how others categorise it. But a distinctive product tends to start from a small ambition. Without answering outside forces motivated primarily by sales, or a critics’ expectation of what is proper, an artisanal distillery without flash and ceremony like The Glenrothes is free to define its values and ultimate purpose: engender a culture of thinking and drinking.

This article first appeared on Aug 7, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.