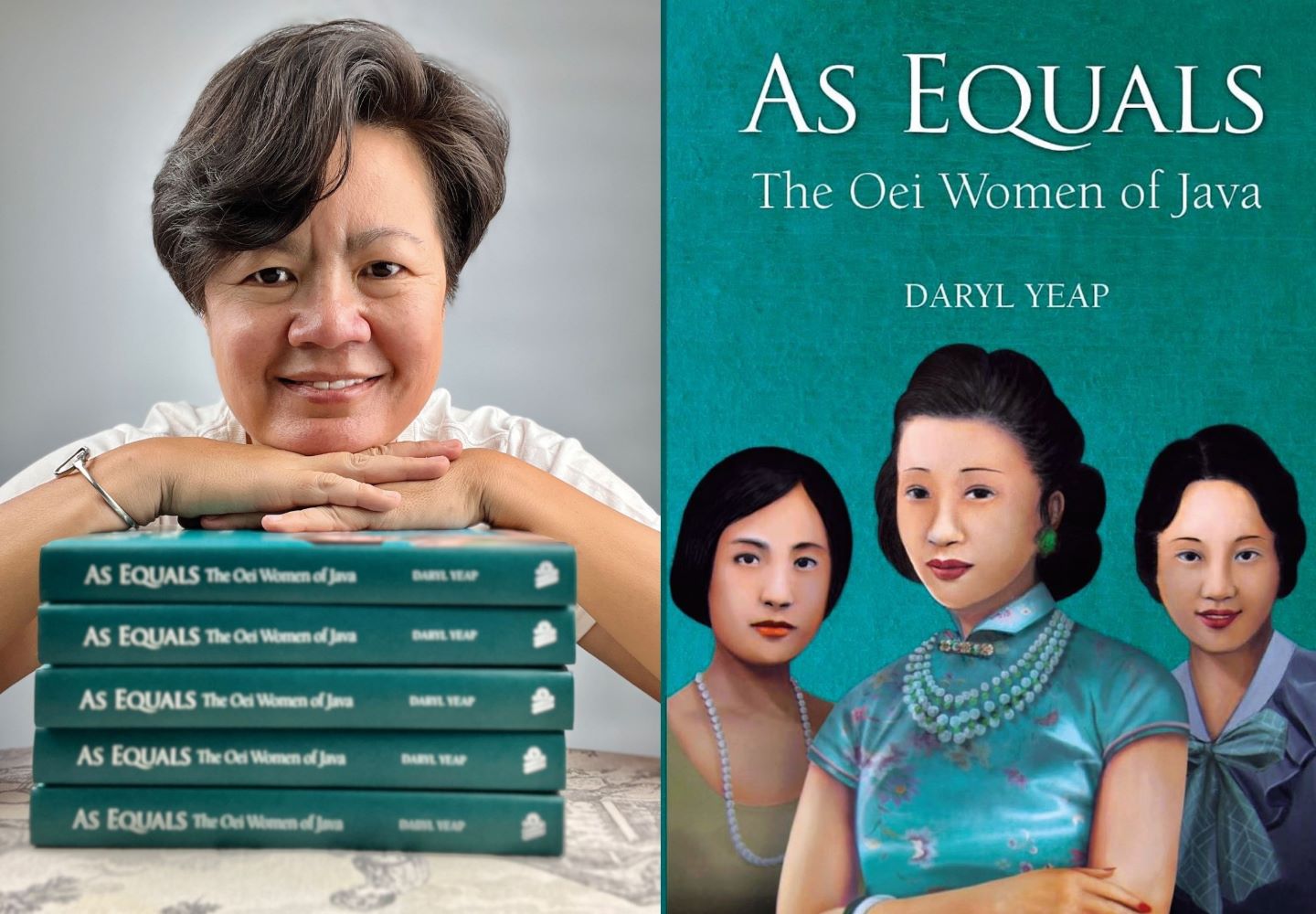

Yeap was formerly a banking analyst (Photo: Daryl Yeap)

When she was growing up, Daryl Yeap heard stories about the Oei women of Java, in Indonesia. No surprise, because two daughters of Oei Tiong-ham, the Sugar King of Asia in the early 20th century, married the sons of millionaire banker Yeap Chor-ee, her great-grandfather. The patriarchs were business partners.

Ida (Bien-nio), the younger of Oei’s girls with his fifth wife Ong Tjiang Tjoe-nio, was a year older than Hock-hoe, Chor-ee’s only son with his fourth wife, Lee Cheng-kin. Theirs was an arranged marriage and the lavish wedding ceremony in 1933 was held at Homestead, Chor-ee’s newly acquired property in Penang.

But the couple were poles apart: Ida was a high-spirited extrovert while Hock-hoe was solemn and introverted. She was flush with her inheritance while he earned a basic salary working at his father’s bank. Communication between them was like “hen and duck”, Hock-hoe would tell his children later.

They divorced after Ida had an affair and bore a son. Unbowed by the scandal or tradition, she moved out with her mother and baby and continued to live as she desired, flying planes, performing in stage plays and having a foreign lover.

There were even more colourful accounts of Ida’s half-sister Hui-lan — aka Mrs V K Wellington Koo — the younger of Oei’s two daughters with his first wife Goei Bing-nio. One had it that three-year-old Hui-lan — Meteor-Heavenly Orchid in Chinese — ran around wearing an 80-carat diamond, which caused a bruise on the pit of her neck! When married to Koo, China’s top diplomat, she charmed her way from East to West with her style, sophistication and daring.

Stories about Oei, a first-generation Semarang-born Chinese who became affluent from trading in commodities and opium and tried to get his intelligent, independent daughters equalised as Europeans, showed the darker side of being modern. “It was not just about rich people and their glamorous lives. There was discrimination and they went through a lot,” Daryl found as she researched.

yap.jpg

On the upside, there was admiration and respect too, especially for Oei’s seventh wife Lucy Ho (Hoo Kiem Hwa-nio) who, at 23, became executor of half his vast estate after he died of a heart attack in 1924. Upright Lucy, a mother of four kids aged one to six and heavily pregnant with her fi fth then, showed her mettle and acumen by dealing with Oei’s wives and sons who were fi ghting for their share of the wealth and meticulously assumed almost all the tasks her husband managed. She was looked up to as the matriarch.

Daryl, Hock-hoe’s granddaughter, is the author of The King’s Chinese: From Barber to Banker, the story of Yeap Chor Ee and the Straits Chinese (Gerakbudaya) , which she worked on from 2008 to 2019. She was a l m o s t d o n e with her first book when she met Lucy’s daughter, Lovy Tanner, in Bangkok.

“I had always been thinking about doing a book about women.” Hearing Oei’s last surviving child recount her upbringing by Lucy, she thought perhaps she could start with the Oei women as “I heard stories about them when I was growing up. That’s how As Equals came to be”.

Direct information was scarce and conflicting. Also, the family had long left Java and were scattered all over the world, as Daryl found when she visited Semarang. “ The current surviving generation do not really know their relations either.” Kian Gwan Thailand in Bangkok, a subsidiary of the Oei Tiong Ham Concern, is the only remaining company of the largest conglomerate in the Dutch East Indies in the early 20th century.

A distant relative from Holland put her in touch with a few people and she connected the dots and pieced things together. “I was using a lot of Wellington Koo’s documents from Columbia University, which has a wealth of information, and managed to get in touch with his eldest granddaughter, Ying-Ying Yuan, based in the US.”

Just as Daryl’s first book was more of an individual story about her forebear, she did not want As Equals to be only about the women. “It has to be about the time; then it makes so much sense. If you set things in context, you see a bigger picture and you realise, ‘Oh my God, they were so courageous’.”

The challenge was picking out the common threads in Hui- lan , Lucy and Ida’s stories: Oei Tiong Ham; the discrimination and suppression of women — for which Daryl used the gruesome practice of foot binding as a metaphor in her prologue; important Chinese families in Java, Malaysia and Singapore from the 1880s to the 1990s; and how the economic policies and politics of the time affected the lives of the three protagonists.

They are “fascinating examples of how life courses are shaped by family histories, international events, societal norms and individual confidence, courage and enterprise”, Yuan writes in the back-cover blurb. As Equals traces how they “navigated events and made modern choices in a complex period between the traditional past and the uncertain future”.

One term that piqued Daryl’s interest as she pored over history books was coverture, a legal doctrine that decreed a woman’s property passed into the hands of her husband upon marriage. He could not sell it without her consent, but could take all the income and profi ts from the property. “Imagine how much more women would have been able to achieve if there was no such thing as coverture. That was what sparked the idea of doing this book.”

She had time to write during Covid-19, but rewrote a lot because her publisher, World Scientific, wanted the book to flow in a storytelling style rather than be a factual, historical account for academics. That was another challenge because, as a banking analyst for most of her career, Daryl had only ever written financial reports until she started on The King’s Chinese. But her financial training helped because “we just don’t write the report; we have to present it to a board. If you’re not succinct or clear, it gets thrown back at you”.

kings_chinese.jpg

“I never imagined I would write a book; I’m more of an active person, into sports and all that. But I enjoy the research and piecing all the information together”, an endeavour that actually started when Daryl’s family donated Homestead to the Wawasan Education Foundation in 2006. Her parents Stephen and Irene Yeap were living there but found it too big with their six daughters working abroad.

“There was all this furniture and artefacts, so dad thought it would be nice to do something to pay tribute to my great- grandfather by starting a social history gallery. Because I was working for him by then, basically managing his personal assets, investments and projects, I took on the task of researching the family. That’s how The King’s Chinese came to be,” says Daryl, who grew up reading The Adventures of Tintin, Dandy comics and books by Enid Blyton.

Writing As Equals was “eye-opening” as she saw how the Dutch viewed Chinese migrants in Indonesia. Oei was rich and powerful but faced humiliation because the Chinese were categorised as ‘Foreign Orientals’ and treated differently from the rest of the community in the Dutch colony. He wanted his family to be treated as equals to the Europeans. He cut his queue, a symbol of Qing suppression, wore Western clothes and engaged European governesses to educate his daughters.

“Probably one of the reasons that drove him to become so Westernised, so modern and so determined was to fight the system.

“I learnt a lot about Chinese history as well, what China went through. It kind of runs parallel: the discrimination of the Chinese by the West, the Yellow Peril and the racism that stemmed during the late 19th century had to do with this idea of modernity. If you are modern, you’re culturally more superior. And people in a diff erent civilisation were looked down on as backward and regressive,” Daryl says.

The strong-minded Oei women rose above it all and held their own against what life threw at them. “They were role models who paved the way for a lot of women in that era.” When Hui-lan was young, she was more into European attire. But after spending some years in China, she showcased the beauty of Chinese fashion by tailoring the Manchu robe into a stunning, modern qipao. Slim and fi ne, she was voted best dressed several times and was known for her glamour among the diplomatic community.

“I managed to see some of her dresses donated by the family to the Fashion Institute Museum in New York. The handiwork on her qipao was meticulous and amazing. She did a great deal to educate the West about the East, even if we cannot quantify the value she brought.”

Lucy died in 1963 at 64; Ida in 1989 at 76; and Hui-lan in 1992 at the age of 103 in the US. She had published Hui-lan Koo [Madame Wellington Koo]: An Autobiography, as Told to Mary Van Rensselaer Thayer in 1945 and No Feast Lasts Forever (1975), but the books had a lot of gaps and some information was not very clear, Daryl says. “I visited her grave in New York. That’s quite something.”

Lucy’s family is mainly in Bangkok and Holland today. “Many of them didn’t know I had started this project. When they heard about it through my recent talk at Columbia University, they got the book, and I’ve been receiving emails from them thanking me for writing the story. Many of them don’t really know what these women have achieved. That was quite satisfying.”

Daryl Yeap will give a talk on 'As Equals' at Badan Warisan Heritage Centre, 2 Jalan Stonor, Kuala Lumpur, on March 9, 10.30am. Admission is RM30 per person but free for BWM members. Visit badanwarisanmalaysia.org to register and darylyeapbooks.com for book details.

This article first appeared on Mar 4, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.