Lim: If you can find just one person to believe in you, then you are successful (Photo: Soo Phye)

Dare to do, no holds barred may well be Malaysian artist H H Lim’s mantra. Like standing on a basketball to make a point about balance; throwing hook, bait and line into a tank and waiting for a fish to bite to test patience; and nailing his tongue onto a table for a project on words.

People called him crazy. He brushes that aside and talks about being lucky and how opting for an unconventional choice led him to Rome, where he lives when not back in Penang for holidays, and countries where he has exhibited over the decades. All because he dared grasp the freedom art promises.

“I was quite rebellious when young. Born like that lah. If you are scared, you cannot do it,” says Lim, home again for his second solo exhibition in the country. The Gaze of Sleepwalkers opened in Kuala Lumpur on Jan 26 at Wei-Ling Contemporary, which also presented his debut show, The Beginning of Something, a decade ago.

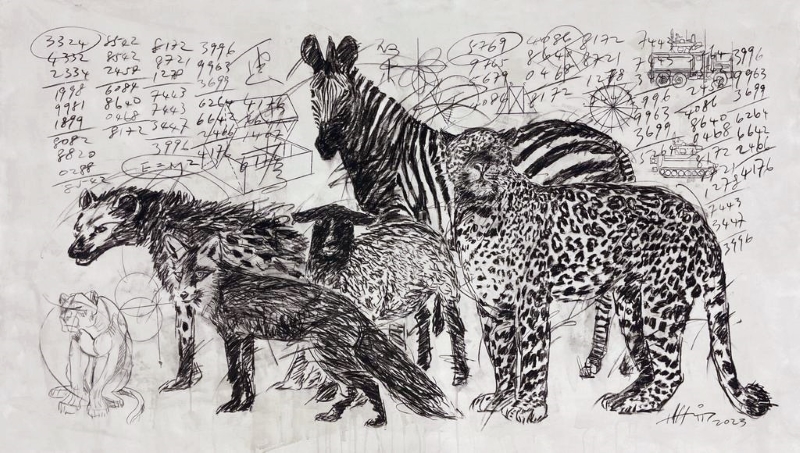

In the current display, a series of 13 paintings and installation pieces, the Kedah-born but Penang-raised contemporary artist draws parallels between the human condition and the surrounding ecosystem. Wild animals big and small coexist within their isolated habitats, observers casting contemplative gazes upon man’s current state of affairs.

“I tried to draw a borderline between the two worlds, ours and that of animals. We observe each other, day and night. They look at us as if asking, ‘Where are you going?’ I don’t know because we are like sleepwalkers.

“Their world, I feel, is on a higher level than ours. We have technology, but it comes from information that teaches us what to do and how. We don’t rely on our senses, unlike animals. Birds and dolphins can sense things from far away. Worms dig a hole and find a home. Humans dig a hole and sell you a tomb.

“We live in a tough, violent world and I’m drawing it. Issues such as human rights and diversity are too big for many of us. I mean, how are we going to live with the way things are or play our part? But I can draw my feelings,” he adds, looking out to the balcony at his Tanjong Bungah condo unit that fronts the sea.

h.h._lim.-_code_3324.jpg

His thoughts swirl from the three disastrous years of Covid and how, barely out of that hard period, there are now wars in Ukraine and Gaza. With detailed charcoal drawings, he captures creatures standing alongside each other in groups, a stark reminder that humans can find balance in the ecosystem, as long as we are sensitive enough to handle what life throws us, “as long as the world does not come to total destruction” with the press of a button.

Charcoal is a medium he is familiar with from childhood and he uses it freely to give intense expressions to his subjects. What’s more, he has found a way to fix the medium on canvas.

“Whenever I saw charcoal, my hands would itch and I’d start drawing all over. It’s relaxing and easy to capture things directly. So, this is quite a meaningful exhibition for me. It’s a kind of diary, drawing what is happening around us now.”

When Lim left home at 20, he told his disapproving father he was going to study architecture. But he enrolled at Rome’s Academy of Art to do sculpture instead, followed by painting then scenography, each a four-year course. Then he did everything he could to get into the stream of things, from performance art and installations to sketching, drawing and painting.

Unlike many who headed to the UK or US because of the language, Lim picked Italy because of its history and baroque and rococo influences. The early years were not easy, and he did his share of washing dishes.

“I was struggling but it was like going to the gym — after you suffer, you feel happy. I felt rich getting to admire all the sculptures and designs in Rome. Everywhere you go, there are statues. I quite enjoyed working and studying”, until scholarships helped take care of his expenses, leaving him free to focus on performance art.

Among his early shows in the 1980s was dressing up as a messenger and going around a particular area for seven-hour stretches, to gather information and send messages. News about the Iran-Iraq conflict and then the Libyan revolution struck him and led to more performance art. Talk about nuclear warfare and dictators with a “fatal attraction between their index finger and the red button” triggered thoughts about sign language and how it, being silent, peaceful, direct and easy, might just be what countries need to connect on an international level.

Along the way, Lim shouted and was fearless. Unlike many artists who pick a subject and stick to it, his art was never the same. “My subject comes from my whole life journey. If there’s a war, I get influenced. I want to use my senses to take what I see and feel and transform it into art language. Most of the things I do don’t stay the same, because even I am not the same anymore. I’m almost 70 now. If I can, I do a bit of this and that.”

h.h._lim_-_gold_in_black.jpg

Focusing on art daily calls for diligence and sincerity, he thinks. “When I translate my intuition, my sixth sense, onto canvas, it turns into reality and everyone can share the idea. But before that, you have to be very strong in your preparation. Do you really have something so interesting or obvious that people can see and feel what you are saying?”

Looking at the money sacks — a recurring motif in Lim’s work — lined up for Gaze, the answer is yes. They reflect man’s relentless chase for wealth and power, as well as the imbalance between opulence and necessity. The 9999K sewn on the cloth sacks denote 100% gold.

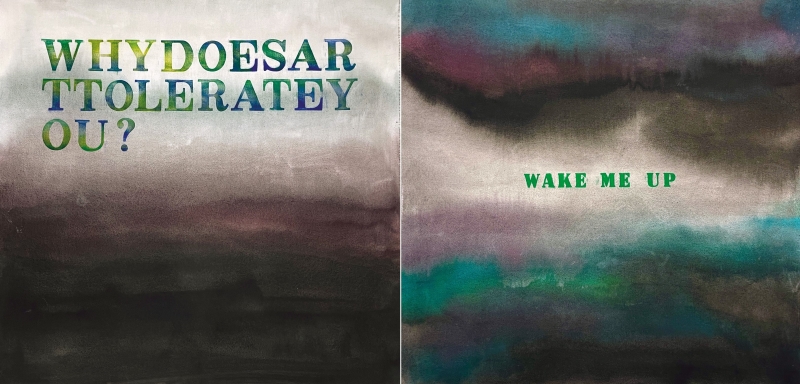

His pastel acrylic paintings are intriguing as they ask, Why does Art Tolerate You? and provoke thought with titles such as Immortality is Dying and Wake Me Up. The last piece connects to sleepwalking in the title, a state of being awake but not fully aware, and from which the artist is reluctant to arouse himself as it would mean leaving peaceful dreams for harsh reality.

Lim explains that he uses abstract forms to present his concepts and evoke the senses because he likes to feel, and also taps his surroundings for inspiration. “If I lived in Africa, I would be influenced by African culture. The same goes when I stay in Italy. I want to tell my story, turning it into very simple language, not something sophisticated.”

Parental opposition made him strong instead of uncertain about his decision. “I’m quite lucky. Maybe because my father — he wanted me to join him in the family’s personal care business — never showed satisfaction over what I did, I became tough. But he taught me an important lesson: If you don’t go causing trouble, people are quite accepting of you. So, don’t be afraid or tie yourself down with regulations. Free yourself to imagine and dream.”

And observe and ask questions. Gaze features new works spawned by the turmoil and unrest in the world today. “I don’t want to go into political opinion but it’s sad to see so many people killed and no one saying anything. All of us have to be quiet. It’s like, we’re also animals; the lion eats [another creature] and everyone looks at it. You can’t do anything. What can we do?”

For him, art is far bigger than a family business. “It’s a responsibility. If we are chosen to tell what we see, we have to be very sincere. That’s why I sometimes have difficulty telling stories in Malaysia. My artworks are not really for some people, as they are quite sensitive. But someone has to tell the story.”

For posterity mainly, because what artists say is not just for now. “One hundred years later, people should be able to say, ‘We really had some problems during this period and not everything was beautiful’. Using my technical capacity and experience, I also want to make it nice so not only will people [see] my opinion but also the beauty, energy and many things within the work.”

Speaking as someone who knows the measure of what he has done, he exhorts: “Do your own thing. If people don’t understand, it’s okay. If they don’t give you attention, go at it until they do. You have to shout, shout, shout because they cannot hear. If people spare you the time, it’s because you have something to say. When they do, that’s just the start; you’d better go back and do your homework.”

hh_lim.jpg

In his initial years abroad, he nursed hopes of returning home but time and work did not allow it. After spending the better part of his life in Italy now, he has become dramatic, like its people, he admits. And romantic too.

“Yes, all my journey is about looking for love. That’s the reason I have stayed in Rome for so long — love keeps me there. If I fell in love here, I would be back in Penang. Love brings me wherever I go and life is so beautiful for that,” says Lim, whose partner Viviana Guadagno is co-director of art space Edicola Notte, which he founded in 1990.

Love also feeds his hunger to create. “Give me another 10 years and I’ll show you what I’m going to do. I have so many things to say, to grab. Give me another 30 years and I am going to change the world!

“In art, we are lucky if we can go hungry to the end — draw that one stroke and drop dead, satisfied. There are many things you need time to understand. The moment you almost do, it’s time to go. Some people never reach that understanding. That’s why I say, don’t worry about criticism,” adds this fervent creative, who wants to do his best yet if approached by museums or galleries.

Asked how he would measure success, he pauses then replies: “If you can find just one person to believe in you, then you are successful. Because that would prolong your immortality.”

As Lim nears the end of his career — “I can feel it because they are beginning to give me a prize here and there” — he eschews sweet paintings for decoration and goes for sentiments instead. “I use art language to interpret my senses. It’s a difficult time to draw flowers and landscapes, sampan and still life. It’s not so right in the current situation.”

Among his latest creations is a permanent installation at a subway station that links to a shopping centre in Shenzhen, China. “I’m quite lucky that people have accepted my way of doing things. Initially, they said I was crazy. I’m doing okay because the museums have my work and I’m quite respected in Asia and Europe.”

That is putting it modestly. He exhibited in Albania in 2005 and following that, Prague, Singapore, Malaysia, China and Thailand. In 2019, he was one of four Malaysians who represented the country at the first national pavilion at the 58th La Biennale di Venezia. The others were Anurendra Jegadeva, Zulkifli Yusoff and Ivan Lam.

Lim presented Timeframes, a collection that encapsulates cerebral and physical journeys within a triptych painting and an installation featuring 28 chairs and four video films. The works capture how he intertwines time, place and memory in exploring meaning in art.

h.h._lim.-_code_4956.jpg

In 2022, he took part in Opera Opera at Palais Populaire, Berlin. Last year, he showcased art at Florence, Abruzzo and Rome in Italy. And his creations are collected and prized by various museums around the world, an achievement that would impress most in the industry.

Sadly, Lim’s father never understood why the youngest of his five sons chose art over business. “In the last period of his life, I was sitting there when he asked my brother: ‘What does he do?’ He still didn’t know or believe in what I was doing.”

But his late mother did and he speaks fondly of her faith in him. He is also thankful for three ideas he “stole” from her for his work.

When he asked her how he could go far, she said there are many ways to express art besides painting. All he needed to do was use different avenues to interpret the concepts he had in mind.

The first step was to find balance, she suggested. And how? Lim started training to stand on the basketball for half an hour. He did it for a year before mastering the feat, pushing himself to the limit until the back of his feet had blisters!

Next, mum ticked patience, which he acquired with his ‘performance’ with the fish. “I wouldn’t go near its territory and it didn’t come to mine. We were waiting to see who couldn’t tahan the waiting.”

Finally, chiding him for being talkative as a child, mum would, playfully, threaten to nail his tongue. “So I did this project about words and how signing is really an international language. You can’t shout or quarrel with others when using it. At worst, you just make a few signs. Maybe then, the world will become more peaceful, like that of the animals.

“If you have balance, patience and language, you will be able to survive. With these three tips, I went on to conquer Europe. It was simple, as my mother said.”

The Gaze of Sleepwalkers is on show until March 30 at Wei-Ling Gallery, 8, Jalan Scott, Brickfields, KL. Viewing by appointment only. (03) 2260 1106.

This article first appeared on Jan 29, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.