Poetry started her writing and it never abandoned her, she says (Photo: Low Yen Yeing/ The Edge Malaysia)

When young Dipika Mukherjee returned home with her locks chopped off, one glance at her strict, conservative father — who felt women should look a certain way — made her go, “Oh dear, what have I done?” Dad did not shout at her. Instead, he quoted Sanskrit dramatist Kalidasa’s poem about Shakuntala and how her beauty lay in her rippling hair.

“He had all these ways of schooling me using literature. When I went to study the subject at the bachelor’s level, we would talk about influences on Tagore from the Irish. I grew up thinking every family was like that because my three brothers loved Lit as well. Then I realised some families don’t read any poems. I had an unusual upbringing. There were always lots of books, in Bengali, Hindi and English, and love for the written word.”

Now a mother herself, Dipika can see how difficult it was for her diplomat father to instil language and culture in the children, with the family moving from Geneva to Jakarta to Wellington, New Zealand, following his postings. “We spoke Bengali at home and had a lot of grounding. He taught us in ways that will stay with us forever.”

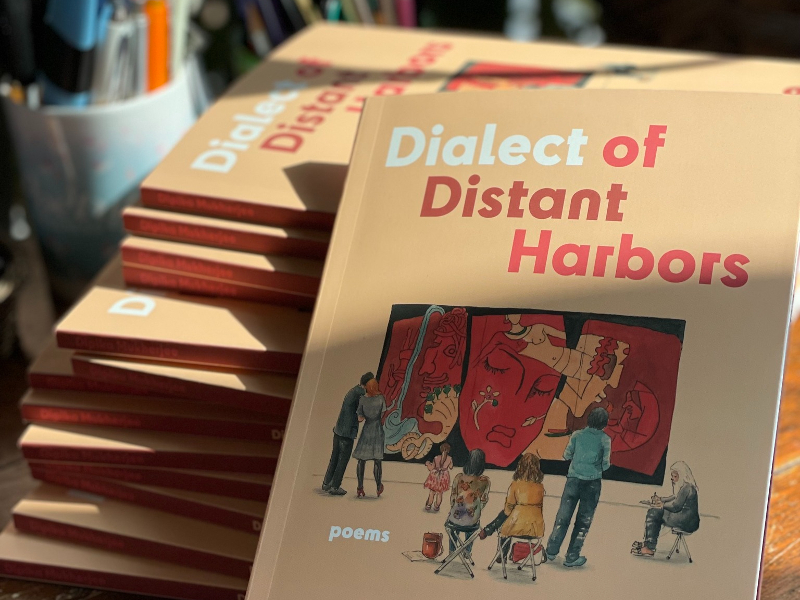

Kalidas Mukherjee, who died in 2021, figures in various poems in Dipika’s Dialect of Distant Harbors. There is one, Bangkok, about her parents meeting and talking even before she was born. Another shows how far he has travelled in his own life, from a rural part of Bangladesh to India, with literally nothing at all after the partition.

At 14, he started working at a homoeopathic clinic to fund his studies and other things. He did his bachelor’s in literature and master’s in philosophy. In the diplomatic corps, he met ministers and kings. “He gave us this enormous height from which we could start our careers. One of the things he instilled in me from very early on was the importance of education because that’s what got him out of poverty.”

dialect_of_distant_harbours.jpg

Standing on the shoulders of writers whose work she devoured and delighted in taught her that those who are truly great hold your hand and make you feel like putting yourself out to embrace the whole world. As happened when she met China’s Su Tong, author of Raise the Red Lantern and Rice.

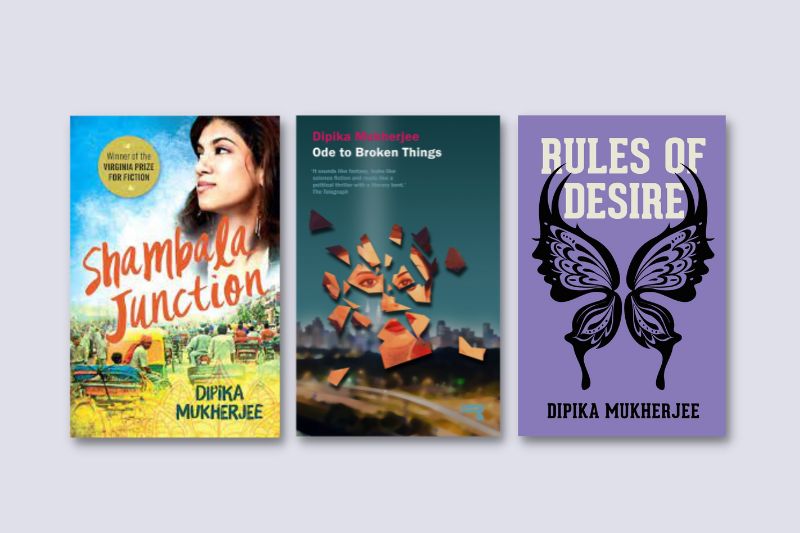

In 2009, Dipika’s debut novel, Thunder Demon, republished as Ode to Broken Things, was longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize. “That was when I thought, ‘Okay, now I can say I have written’. It was an amazing experience — agents started contacting you,” she recalls.

Su Tong was a fellow nominee for The Boat to Redemption, the eventual winner. At the Shanghai International Festival for an event, she met him. “He is so big. I had read Rice in college and fallen in love with it because it was so dark, so beautiful. I was 20, impressionable.

“He walked in and I said, ‘Hello, so pleased to meet you. Both our books were considered for the Man Asian.’ He looked kind of confused after the interpreter translated that. Then I said, ‘When I saw your name on the list, I knew you would win because there was just nobody else who could possibly win.’

“After the interpreter’s translation, Su Tong turned to me and said, ‘Oh no, no, no. It was a mistake. You should have won.’ He was so generous and he held my hand.

“What expansiveness of spirit — and that is so integral to what we do. Because literature is really about expansiveness of the spirit. That was when I found that people who are truly great are also humble and generous. I really hope to emulate these big people.”

One could say Dipika, an Indian national married to a Malaysian and a permanent resident in the country for more than two decades, is headed in the right direction. She has been mentoring Southeast Asian writers and has edited five anthologies of fiction from the region: Endings and Beginnings Fruit, Bitter Root Sweet Fruit, Champion Fellas, Silverfish New Writing 6, and The Merlion and Hibiscus.

dipika_mukherjee.jpg

A writer herself, she has three novels — Shambala Junction (winner of the UK Virginia Prize for Fiction), Ode to Broken Things, and Rules of Desire — and three books of poetry: The Third Glass of Wine, The Palimpsest of Exile and Dialect of Distant Harbors. The last was released in 2022 by CavanKerry.

Penguin Random House (SEA) will publish a collection of her travel essays, tentatively titled Writers Postcards, this year.

Dipika writes for World Literature Today, Asia Literary Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, Newsweek, Los Angeles Review of Books, Hemispheres, Orion, Scroll, Options, The Edge and other publications. She is also a contributing editor for Jaggery and teaches short fiction at StoryStudio Chicago and novel writing at the Graham School, University of Chicago.

Other institutions she has taught at include the University of Chicago, Shanghai International Studies University, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and International Islamic University Malaysia.

Poetry started her writing and it never abandoned her, she says. At 11, she had submitted three poems to a children’s page in a New Zealand newspaper of which two were published. “When people started saying they saw my poem, it struck me that this is something great — people read your work.”

Who reads poetry? Asked if she thinks about that when writing her poems, she says, “All the time. I think poetry is something you cannot not write if you are a poet. It’s like you have to write it. There is something that comes to you and it can only be a poem.”

Many are daunted by poetry, she notes. “A teacher throws a poem at you and says, ‘Tell me what it means.’ That’s the part people are resistant to; the poet uses images readers cannot connect to. There are lots of people writing nowadays and poetry doesn’t have to be inaccessible. Our mindset is that it needs to be unravelled and unwrapped in ways that are difficult. It doesn’t have to be.”

_dipika_mukherjee_george_town_lit_festival.jpg

Dipika had her sons at 26 and 28 and completed her doctorate in English (sociolinguistics) a year later at Texas A&M University. She remembers that decade of her life as “a bit of a blur”. Fiction came back to her when she was teaching at NTU, her first academic job after her PhD.

Penguin approached her in 2002 about doing a collection of Southeast Asian fiction. She got together with various academics — two of whom were Kirpal Singh and Mohammad Abdul Qayyum — and started working on The Merlion and Hibiscus, a book of short fiction by writers from Singapore and Malaysia.

“It was a great experience because I got to meet the who’s who of literature in this part of the world — K S Maniam, Catherine Lim and Alfian Sa’at. While I was editing the book — this may sound a bit boastful — I kept thinking, ‘I can do that. I can write like them. I should try.’ That was what got me back into writing — I started to write little short stories.”

Chicago has been home for Dipika since 2012, after Shanghai, but she visits Malaysia about three times a year to mentor writers, give talks or conduct workshops, and spend time with the large family on her husband’s side. At her condominium unit in Kuala Lumpur, the glass doors are open and the air conditioning is not even on. “I love it here — 25 degrees! I’ll be going back to freezing weather.”

From her experience of The Merlion and Hibiscus and subsequent projects, Dipika notices Malaysians do not like to revise their work. They often do something and send it off for publication right after it is done. “If you do not edit your own writing, it really shows — silly little typos, overused adjectives.”

The good thing is that there has been a surge in writing, thanks to encouragement and exposure by stalwarts such as Sharon Bakar, a teacher-trainer who teaches creative writing, and publishers like Amir Muhammad of Fixi, which prints very cheap books and does a good job of getting them out to young people.

In the West, there are many gatekeepers — publishers, editors and proofreaders. Writers here don’t have that; at most, they have a friend who will read their copy but is a little shy to say it’s garbage. In the US, they will tell you if a part sucks and to take it out.

“I hope things change in Malaysia because there are so many stories still untold from here. I want to be a part of the group that helps voices be heard. Sharon and I have been talking about reinstating some sort of writing award as well.”

In 2015, Dipika founded the DK Dutt Award for Literary Excellence in Malaysia to honour the life of Delip Kumar Dutt (1929-2015), an educator and avid sportsman. She and Sharon edited Champion Fellas, a collection that represents the best stories entered for the prize in its inaugural year, on the theme of sports. The winning piece was by Hanna Alkaf, with runners-up by Marc de Faoite, Saras Manickam and Tina Isaacs.

This article first appeared on Jan 16, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.