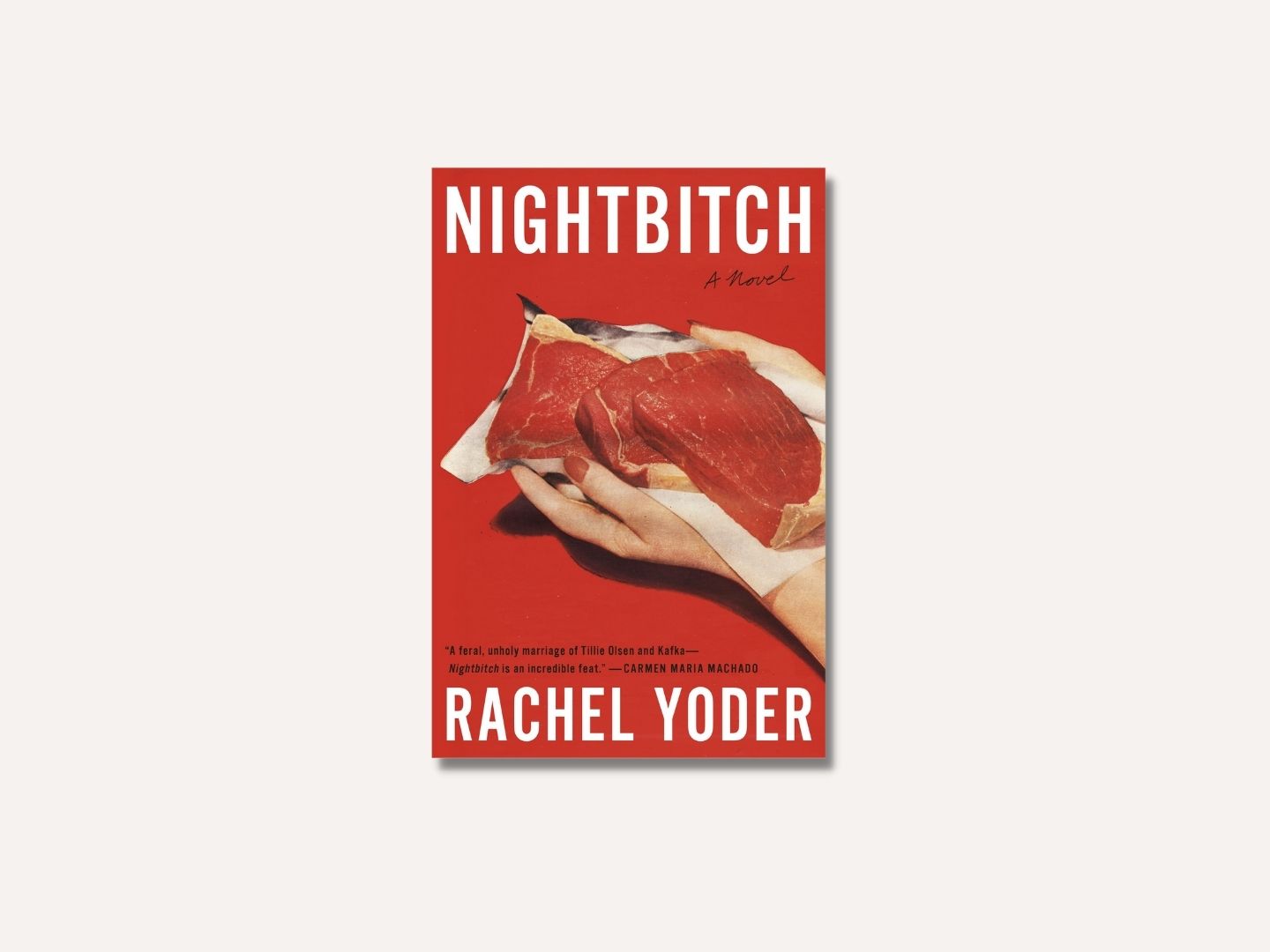

The surreal and magical happenings in Nightbitch allow Yoder to explore motherhood without restrictions (Photo: Doubleday Books)

"I think working mother is perhaps the most nonsensical concept ever concocted. I mean, who isn’t a working mother? And then add a paid job to it, so what are you then? A working working mother? Imagine saying working father,” says the protagonist in Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch. Her debut novel does not hold back as it explores the transformation of “the mother” into “Nightbitch”.

From a studio artist to staying home full-time with her two-year-old son, the middle-class protagonist, who is referred to as “the mother”, starts noticing changes in herself: her canines sharpening, her hair growing, a suspicious bump on her back that threatens to sprout a tail and an odd craving for raw meat. Her self-proclaimed moniker “Nightbitch” is punchy as it perfectly encapsulates this darker and freer being the mother is morphing into.

The initial pages are made up of long, breathless sentences sprinkled with commas and very few full stops. The words are unencumbered by quotation marks, and for emphasis, Yoder employs italics and the occasional exclamation. Like how new mothers are thrown into the deep end, the book gets right into the nitty-gritty of her transformation: “I think I’m turning into a dog, she said to husband when he arrived home.” As the novel progresses and her transformation evolves, the text is less panting for breath and more in step with her “feral femininity”.

rachelyoder-imagecreditnathanbiehl.jpg

The monstrous female may not be an unfamiliar trope, but Yoder’s prose is cheeky while still tackling darker and more gruesome themes. From start to finish, Nightbitch reads like a rolling consciousness, unfolding events of the mother’s life in between her never-ending thoughts, anxieties and observations. It feels like the reader has been planted in the centre of her brain, exhausted by the tirade of doubt that floods her system, and veers from bliss to deep panic as she transforms into an animal.

Her husband’s work takes him out of the equation from Monday to Friday, leaving the mother with the Herculean task of raising her child alone. Resentment seeps from her observations. “She wanted to exit, but it would be really inconvenient for her husband, for the entire family, as he put it, so she stayed.” Her hidden feelings and unthinking husband remind me of French existentialist Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, when she explains, “It is perfectly natural for the future woman to feel indignant at the limitations posed upon her by her sex. The real question is not why she should reject them: the problem is rather to understand why she accepts them.”

Why does the mother, in fact, accept them? She excuses her husband’s apathetic behaviour and constantly justifies his actions. As she swallows her feelings, her dog-like attributes increase. Although she shares her transformation with her son, she feels a sense of calm by keeping her husband in the dark. “Her secrets were the only things these days that were purely hers, things apart from mother and wife and middle-aged woman.” It is only when Nightbitch is free in her fervour does she no longer accept the limitations imposed upon her.

Caged in the monotony of “The Schedule”, sprinkled with mundane classes for her child such as Book Babies and Gymnastic Jam, the mother thirsts for intellectual stimulation. “She had done the ultimate job of creation and now she had nothing left. To keep him alive — that was the only artistic gesture she could muster,” she bemoans. She reaches for her art but is drained from constant parenting, desperate for a respite... even if just to sit still. She attempts negotiating change with her husband but is met with resistance. “Instead, when she tried to bring up the division of labour, the invisible labour of her life, the psychic load, he would offer something like I suppose the money I make means nothing, and of course that wasn’t what she was saying, not at all.”

Diving headfirst into the internet for an explanation for her new dog-like attributes, the mother only finds a sort of peace when she discovers a book by Wanda White called A Field Guide to Magical Women. She is drawn to the mythical female creatures. A sort of summary of the book: “To what identities do women turn when those available to them fail? How do women expand their identities to encompass all parts of their beings?” Constantly revisiting White’s tome as a way of comforting herself with her own canine changes, the mother looks to White’s creatures, WereMothers of Siberia, the Bird Women or the ambitious Slaythe, hoping to see herself in them.

While the mother yearns for White to reply to her emails, her other relationships with women are less positive. She finds it impossible to relate to her old friends, such as the videographer and the working mom, as they seem to be fulfilled in a way the mother feels unable to grasp. The mother’s interactions with The Book Mommies show reluctance on her part. “While she would not actively avoid a friendship with a woman because she too was a mother, she felt that to begin one merely because of this shared motherhood was repugnant.” Already we see signs of resentment as she herself has been reduced to just mother, no longer artist and person in her own right.

By referring to The Book Mommies as “jackals” — an animalistic description reminiscent of her own physical changes — it indicates that while she keeps them at a distance, she yearns for their community. This tenuous back and forth is where the mother sits throughout the novel, creating an immense tension that pulls you to the end, unable to put the book down.

With her transformation, the protagonist is no longer referred to as the mother; rather, she has fully embraced her new moniker, whether in human or dog form. As Nightbitch, she is feral and free, a wild combination of violence and weightlessness. Her ability to see art and create it has been reinstated. When questioned, she says her art piece is “about the wildness of motherhood, the modern mother’s impulse toward violence, the transformative powers of anger”. These are themes present throughout Yoder’s book, creating art within art.

While Nightbitch starts off as an ode to the difficulties of being a mother, striving for perfection and being completely fulfilled by motherhood without a professional ambition, as Nightbitch reveals herself, it emphasises how mothers are capable of just about anything. “That entire week, in fact, she wore whatever she cared to, day and night, ripped or stained or leather or linen. She became more powerful and more terrifying.” There is a cathartic release at the climax of Nightbitch, which straddles fantasy and reality. The surreal and magical happenings allow Yoder to explore motherhood without restrictions, and her Nightbitch — the mother’s form of freedom — celebrates the monstrous female in all her glory.

This article first appeared on Jan 10, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.