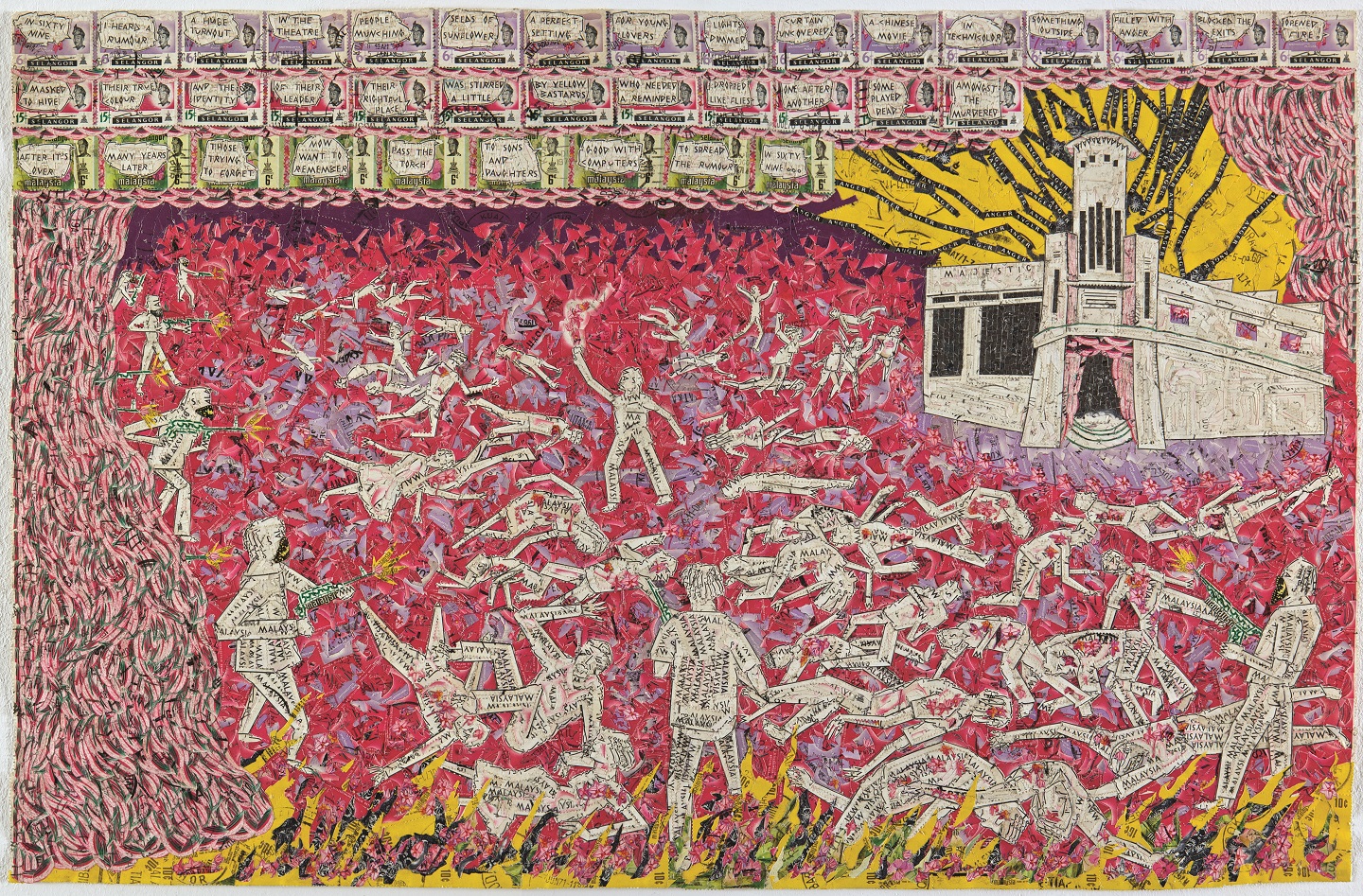

Don't Spread Rumours (2012), postage stamps and polyvinyl acetate glue (All photos: National Art Gallery)

Chang Yoong Chia,43, is an artist who pays impeccable attention to detail, so much so that it comes off a little intimidating. His latest exhibition, Chang Yoong Chia: Second Life at the National Art Gallery, serves as a survey of his artistic journey that spans over 20 years. The title points to the renewal and reuse of materials that tend to be discarded through art making. A walk through the exhibition provides one with an abundance of anecdotes, be it through his paintings, stamp collages, ceramics or even seashells.

As a whole, the exhibition feels like an invitation into this private and mystical world Chang has created. It has three curators: Tan Hui Koon from the gallery, Chang’s wife Teoh Ming Wah and Beverly Yong from Rogue Art. The works are grouped under four sections: Flora and Fauna, The World is Flat, Immortal Beloved and Quilt of the Dead.

Flora and Fauna sees a collection of black-and-white paintings selected by Teoh. Chang comments: “[Teoh] being my wife, knows me on a more personal level. Therefore, it is fitting that she oversees Flora and Fauna as the paintings come from my experiences while growing up.”

Chang is the second of three siblings; he has a sister four years his senior and another five years his junior. “I think I was quite alone as a child, so I played quite a lot in my garden using my imagination. That is why a lot of these paintings look the way they are — it’s like me playing in my small world,” he explains about the surreal nature of his works.

Observing the paintings in Flora and Fauna, one is able to identify that the dominant image among the exhibits is a rabbit. Chang recalls, “We had a lot of rabbits and they reproduced very quickly, to the point where we couldn’t handle them anymore and ate them all up. The rabbit is like a self-portrait as I was born in the Year of the Rabbit, and it serves as a reminder of life and death.”

Chang gestures to a work called Happy Garden. A large rabbit rests on the ground while a man places his hand on the creature’s back. Other animals and human figures are scattered across the painting, some cleverly hiding in between the twists and turns of the foliage. The painting and its title refers to the neighbourhood where Chang was raised, near Old Klang Road in Kuala Lumpur and known in Malay as Taman Gembira.

He explains: “The images here are about my experiences playing in my garden with the animals. We had a lot of animals — chickens, ducks, tortoises, turkeys, quails and rabbits. Most of them were reared for food. We also had trees of mango, banana, coconut and mata kucing.”

He clarifies that the male and female figures are representations of himself and his wife, painted from a non-outward perspective. “When I paint, I feel how I look like; I don’t look in the mirror and paint how I am seen by others. It’s the same with my wife.”

Male figures dressed in office attire appear throughout other paintings in Flora and Fauna. “I’m imagining myself as an artist who is running away from a normal life, which is doing a nine-to-five job,” he says.

Expressing his thoughts on being a painter, he says: “I feel painting is a very isolated activity. Sometimes, as an artist, you think about what your role is in society, how you play a part in society. Painting is very personal and my images are very personal, so I feel everything [I make] is very isolated.”

This revelation led to him exploring different materials and methods of telling stories through his paintings. He did this in hopes of forming a connection between his intense, personal world and the outside.

Maiden of the Ba Tree was the first work that saw Chang properly implementing this change. A series of 35 porcelain spoons are laid out, each one acting as a panel on a storyboard. A woman sits on the ground while her son stands beside her and they are sheltered by a leaf above their heads. She begins to tell a tale. The son supposedly leaves her while she sleeps; she awakes, yearning for him. Much time passes by, only for the reader to realise that the son had never left. It was instead the mother who chose to ignore him.

Life Experiences

Chang explains, “This reminds me of a traditional Chinese meal, families gathering at a round table. Your relatives and elders would always be asking, ‘How are your exam results? Do you have a boyfriend or girlfriend yet?’ and all you’re trying to do is survive. It’s a generation gap; one that is very hard to close. I was trying to express that.”

Chang has participated in a number of art residencies. The time spent in foreign lands has definitely been eye-opening for him. He recalls that during a Yogyakarta residency,“I was staying in a kampung and trying to create an Indonesian narrative. When I was there, the Merapi volcano began to erupt. People were worried because an eruption is, of course, no laughing matter. It can kill and has killed before. I really felt the tension and anxiety."

Despite such hazards, there are those who can do all but leave, such as the local farmers. “When there’s an eruption they will run away, but return the next day to tend to their livestock. This is their job; it’s their way of life and source of income.”

He recounts a similar incident during a residency in Japan. “I was talking to a friend, his phone rang and it was an earthquake warning. [An app] warns you about 30 seconds to a minute before a quake. Everybody in Japan has the app. When they see that message, you can see their faces change. His wife called him and he was assuring her everything was all right. [Malaysians] are blessed in that we don’t experience this. It’s also another way of looking at life. That’s why I enjoy going to artist residencies. For a very short period of time, you get to experience a little bit of something entirely different from your own life.”

Details about the world were not so easily and accurately obtained when Chang was younger. Postage stamps were one of the few sources of information about foreign countries, he says. “If you get a stamp with an image of the pyramids in Egypt, you would think, ‘Oh, this is what the pyramids look like’. Our impression of the world was slowly formed through collecting stamps. Now, because of the internet, stamps are being phased out.”

However, he points out that stamps may not be the most accurate sources to obtain knowledge.“The information from stamps comes from ‘the top’, as they are all issued by countries; the text and images are approved by the governments. I wanted to make this work, to mark this time where information from ‘the top’ and from [the internet] collides.”

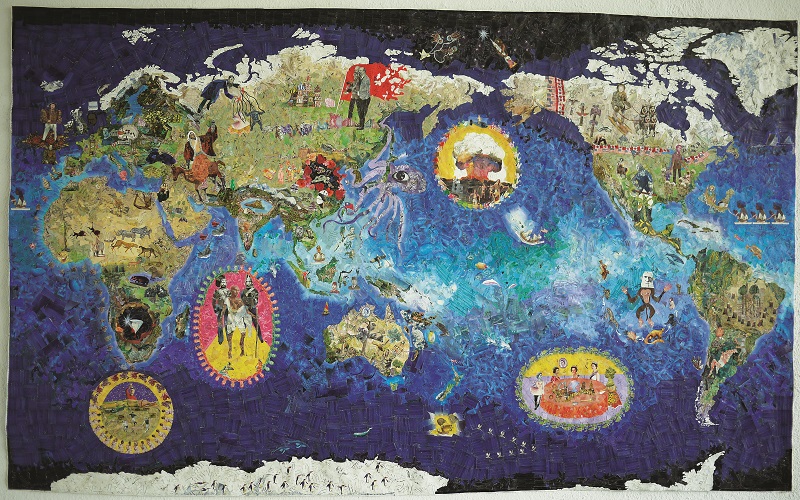

It can be quite hard to believe that Chang’s collages are entirely absent of paint. Each stamp is assorted and categorised, then meticulously cut and reassembled to form the desired shape or patch of colour. Present in The World is Flat is a rather comical rendition of the world map: penguins, British monarchs, a Russian communist leader, a diamond and an octopus are just a handful of the images on the map. “The images and the things that happen in this [collage], a lot of it [comes from] my research using Wikipedia,” Chang remarks.

Asked how he went about acquiring the stamps, he replies, “My uncle is a stamp dealer, I could buy them from him in kilos.” He explains that the more common stamps are bundled together, while the rarer ones are picked out and sold at a different rate. “Another source would be flea markets. Other times, I would ask my friends to give their stamps to me. If I really needed a stamp, I would go to a specialised shop and buy it.”

Stamp collages also appear in the section titled Immortal Beloved. The stamps in this series contain what Chang refers to as “evidence”. He explains: “When I was going to flea markets collecting stamps, I found certain stamps had different marks attached to them.” Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me makes use of stamps from the Federation of Malaya and Singapore, both of which have postmarks that read, “Malaysia: as sure as the Sun will rise”.

The postmarks speak of the formation of Malaysia in 1963, which included the merger of Brunei, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. And indeed Malaysia did rise, but it is a different country from what was referred to.

Chang created more stories based on the “evidence”. Don’t Spread Rumours tells the tale of dark times in Malaysia’s past; a chaotic scene, with bodies lying across bloodied streets. Figures on the edges of the work are armed while a lone figure in the centre stands firm wielding a weapon of his own. Racial riots broke out on

May 13, 1969, in Malaysia and the stamps used in this work were circulated during the mid-60s and 70s. The postmarks would read, “Don’t spread rumours”.

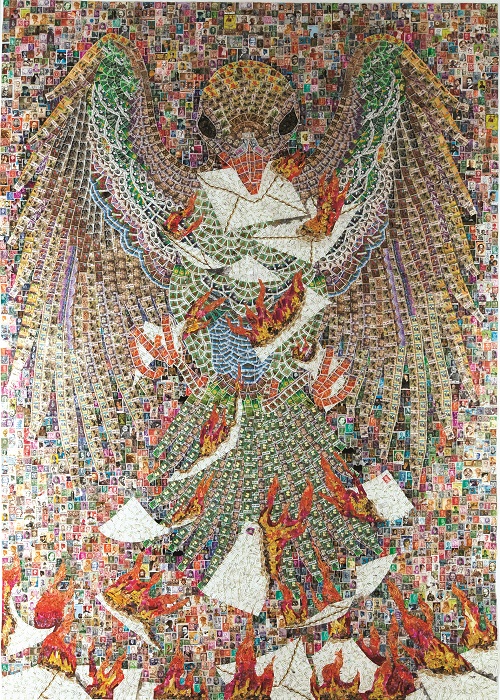

Immortal Beloved is also the title of the largest stamp collage and the largest work in the exhibition. Almost seven feet in height, it is quite a sight to behold. The story in this work is of the celebrated composer Ludwig van Beethoven. “The title comes from Beethoven’s love letters to someone called Immortal Beloved. For a long time, people tried to find out who this person was and they might have narrowed it down to a few people. But what I’m interested in is the fact that Beethoven was a giant, an icon in human civilisation. But there was this person he confessed his love to, and it was someone nobody knew,” Chang points out.

A multitude of stamps with faces make up the background and a large bird-like creature is carrying letters with its beak. Perhaps the faces refer to the unknown identity of Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved.

Quilt of the Dead is a large cloth with portraits of deceased loved ones embroidered on it. The project began in 2002 out of a curiosity about obituary photographs. A year later, Chang decided to transform Quilt of the Dead into something much larger in terms of physical size and context. “Some of the pictures I took from newspapers, some are of family members and others from my friends. This project will end when this quilt is 10ft by 10ft.”

He explains that the project is based on his grandmother’s passing when he was 17. “My aunt is a very staunch Christian and my uncle, a very staunch Buddhist. Both sides were trying to convert her [before she died]. What I saw of this process was that it had nothing to do with her dying and the situation detracted from what it really was. I felt that I didn’t properly mourn for her, I just saw this phenomenon happening.”

“At first it was just out of curiosity about obituary photos, but I realised it was about my grandmother and the universality of death. Everybody will experience death eventually — it’s something we all have in common. I decided that it’s something I could express and share with others.”

Chang has had the opportunity to expand the project in the form of workshops. “My wife and I would ask participants to bring portraits of their loved ones who have passed on — it can be a relative, a friend or even a pet. During this process, we would have conversations about death.”

He affirms that the project has not ended and is unsure when he will finish it. “I want to elevate this even further before I finish it.”

The sheer diversity and number of artworks in his exhibition prompted me to ask him, “What do you hope visitors will take from it?”

He replies: “I never thought about that, even during the process of planning and after the launch. But after looking at the reactions, I really enjoy seeing how people respond to the works. As a viewer, you bring a piece of you, you bring your own taste, your own ideas, your own baggage and those parts of you interact with the works. For me, that is good enough.”

'Chang Yoong Chia: Second Life at the National Art Gallery' is on at Gallery 2B, National Art Gallery Malaysia, until Jan 31. See here for more info. This article first appeared on Dec 17, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.