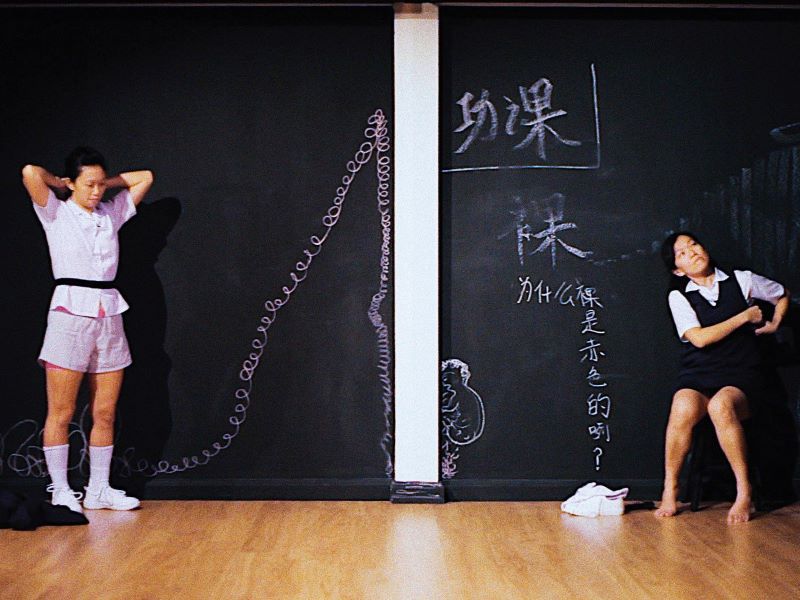

Lee (left) and fellow dancer Tan Bee Hung (All photos: Five Arts Centre)

Dancers are not verbose by nature because their closest language is their body, Lee Ren Xin thought. But when she wanted to participate in vocal exchanges socially, “it was hard for me to take up space and express my truth”. Talking to friends in dance, she found this was something they had in common.

Voice is a significant element in Anggota 2: Re-Member, the choreographer-cum-dancer’s new work now showing in Kuala Lumpur. “The creation process was like a practice for me to hear myself, hear what I want and also what the other person wants,” Lee says, recalling her and fellow dancer Tan Bee Hung’s experience of listening to how their body feels and its needs, desires and capacity to decide.

In the show, the pair uses voice with sounds, not words. “We want to see what sounds come through if I want to channel how my shoulder feels, for example. It was scary initially because we’ve been taught that is something you need to keep to yourself.”

Like movement, voice or whatever comes out on one day may not be the same on another because the body is not in the exact same condition, Lee adds. “This work is sort of about intimacy with oneself, with how you allow your body to just be, with accepting whatever is coming through and not judge.”

Dancers may be conscious of their bodies, she agrees, but they tend to ignore what it tells them. “As a student, I thought pushing beyond pain was always good. Ironically, I learnt to dismiss a lot of signals from my own body despite being very aware of it. Bee Hung felt her body was like a tool for the choreographer to fulfil her/his larger vision.

“Controlling or hiding our bodies and constricting it from what it needs to do — that is kind of the impetus for this work.”

anggota_2.jpg

Re-Member arises from Anggota, which won Lee Best Choreographer in a Feature Length Work and Best Group Performance (alongside Tan) at the 2023 BOH Cameronian Arts Awards. It picks up themes and questions she spent three years exploring for Jalan Harapan, a site-specific project on an actual road of that name in Petaling Jaya, and surrounding areas such as Section 19 and SS2.

Those public performances came about in 2017, when she was working in studios and theatres a lot. If she were to ask her neighbours to go watch her show, she wondered, would they connect to it?

“I started worrying about what I was doing day in and day out, and its relevance to the people living near me. So, I set myself a daily ritual: Spend one to two hours walking around the area and see what happens. After a few weeks, I arbitrarily started to dance, just to see if there was space for it in the neighbourhood. What are people’s relationships to dance? What does it mean to them?”

Was she comfortable performing out in the open and having passers-by stop to look? “We actually had this conversation: Why don’t we feel free to dance? Movement, communally, was a very natural thing long ago. Nobody dances together anymore. Why?”

Through ritual and repetition in Jalan Harapan and her other work, Lee explores ways of inhabiting space and the spaces inhabited, how one shapes the other. There is also the aspect of how the body reflects, embodies and co-creates with place and time.

Going back to listening to the body, Lee reckons the average person would be prompted to think about hers because of medical reasons. “I’m trying to make a space where maybe the body is larger than us, where maybe the body is all [parts] of thousands of ancestors just being beside me.” Which could explain one of the connotations of anggota, as reflected in the show. In Malay, the word refers to a limb, a member of an organisation or part of a larger whole.

lee_ren_xin.jpg

“For a long time, when I was younger, I always felt very replaceable. If I couldn’t be there, someone else would. I felt like a soldier, there to fulfil a role,” Lee says.

There is also anggota keluarga, being part of a cultural environment and growing up in it. “My body is kind of like a lineage of my grandparents and my parents. There are literal genetic remnants.

“I was reading about intergenerational trauma, but also good things like resilience and joy. How does the body embody that in certain situations? Where did I learn or inherit such feelings?

“Anggota, for me, also means parts of the body. Does mine feel good working this way? Can it continue like this? People talk about dancers retiring at 35. What they don’t say is, with a lot of disabilities. Anybody can dance at any age. My body wants my acceptance, to be more at ease and comfortable, and for me to truly trust it.”

Re-member is the act of assembling and putting back together again. “It means a more conscious awareness of what I want to nurture myself and with the people around me.”

Lee recalls that growing up, she always thought what the teacher said about her body was the truth. “I want to take up space with what I feel is true for me and speak for myself. This was not easy for both Bee Hung and me, it took some time.

“Last year, I was trying to find what it meant to choreograph but also respect the agency of the dancer I am choreographing for. This year, I have been able to find a balance. When Bee Hung moves less, I don’t have to make myself small or do less to make sure we are equal. When I truly believe her body is powerful enough to exist in that space, how I want to be does not diminish her space. It’s like feeding off each other — there is more stillness and more motion.”

'Anggota 2: Re-Member' will take place at Five Arts Centre studio, 9th floor, GMBB KL, on Sept 23 & 24 and from Sept 27 to Oct 1. Tickets and details on CloudJoi.

This article first appeared on Sept 25, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.