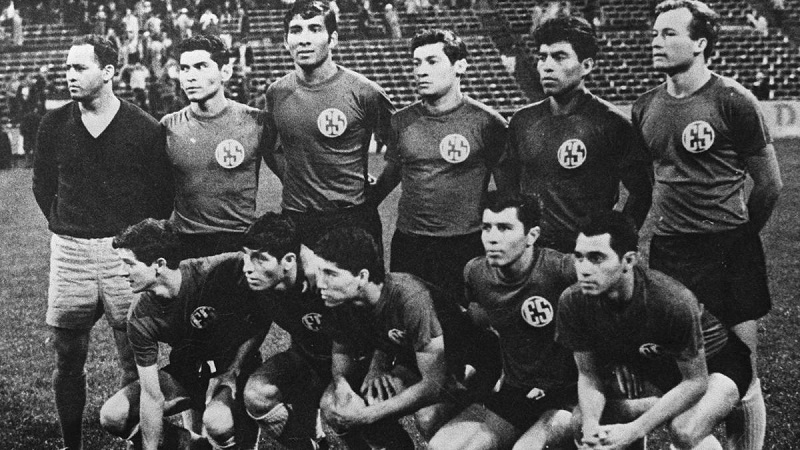

My late father, Emeritus Professor Tan Sri Khoo Kay Kim (in stripes) playing for the Under-21 Perak state team sometime in the 1950s. It was he, an ardent advocate of the beautiful game, who introduced me to football. (Photo: Eddin Khoo)

One American summer’s day, the poet Christopher Merrill comes across a boy juggling a football:

“He wheels around, he marches

over the ball, as if it were a rock

he stumbled into, and pressing

his left foot against it, he pushes it

against the inside of his right

until it pops into the air, is heeled

over his head — the rainbow!”

All through the centuries, what has the beautiful game been, if not the art of chasing the rainbow? When the Chinese in the Han dynasty devised a competitive game they called cuju (simply translated as kickball), they set apart two teams on opposing sides, allowed rough play and handling, though kicking the ball made of hemp remained the principal objective, and shaped its goal, as most accounts suggest, in the shape of a crescent moon.

As ball juggling spread throughout the world, the stylised vocabulary of that game, which came to be known as football, would evolve. Within this region, the art of suspending a rattan ball in a group for as long as was physically possible was played in the Malay Peninsula and Thailand under the name of sepak raga, and introduced elements of the crowded lob and aerial dynamic that would embellish this game with the suspended hands.

arton1358.jpg

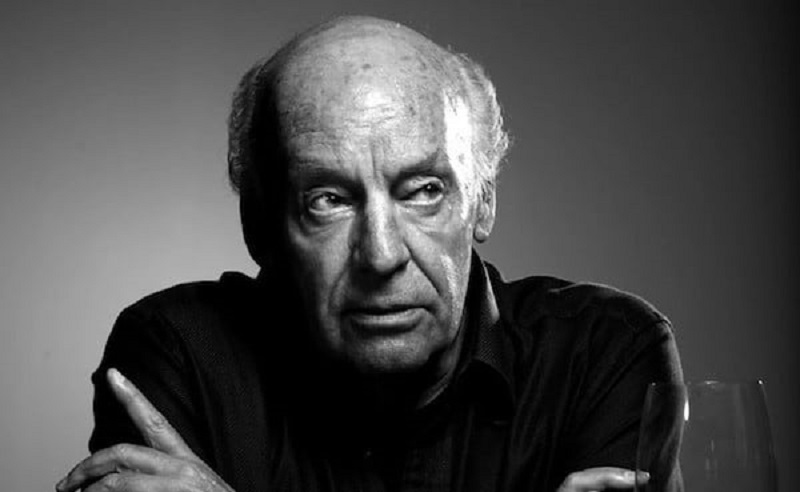

“The history of football has been”, as the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano writes in his beautiful Football in Sun and Shadow, “a sad voyage from beauty to duty”. As an obsession formed around the one game that truly colonised the world, so did the football industry build its edifice, culminating in that festive global craze held once every four years — the World Cup. Known initially as the Jules Rimet Competition, after its founder, it helped, paradoxically, create the curse of “professionalism”, yet at the same time unravel the wealth of vernacular styles that has made the game one of the richest cultural forms the world has come to know today.

“Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that,” the legendary Liverpool manager Bill Shankly once said by way of hyperbole. That hyperbole, understood in real terms, has meant football encapsulating — in great parts of the world — all the forms of a national culture and character. Ranging from the unpalatable antics of football hooliganism and national tensions played out on the football pitch, to footballing styles defined by distinct cultural idioms, football has been described as the most immediate and elemental form of contemporary theatre.

When the brilliant Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski began his profound study on the culture of warfare, he settled first on the long tribal tensions between the nations of El Salvador and Honduras. When the Honduran team beat El Salvador 1-0 in 1969, those tensions spilled over when an 18-year-old girl, Amelia Bolaños, watching the match on television, rose from her seat, ran to a desk, drew her father’s pistol and fatally shot herself in the heart, offering herself as martyr for the shame of her fatherland. Kapuscinski duly entitled his book on wars, The Soccer War.

el-salvador-honduras-3-2.jpg

The pitch, that place of elemental theatre, captures both an illusion — best encapsulated in that Portuguese phrase of lament each time the Brazilian team loses, É brincadeira or “it’s just a game” — and a space of intense beauty, captured in that other irrepressible phrase, O Jogo Bonito or “The Beautiful Game”.

Introduced into football parlance by Waldyr Pereira, better known as Didi, the Brazilian midfielder of that sultry 1958 World Cup winning team, the phrase marked all those aspects of singularity, eccentricity and stylishness that inspired the game. Increasingly, the more singular the style and the more unpredictable the character, the greater was a player’s elevation in the pantheon of footballing names.

At the heights of the beautiful game, players were bequeathed the highest honour earned on the pitch — the sobriquet. Garrincha, the Brazilian wizard of the right wing who used his deformity (he had one leg shorter than the other) to trick, then nip his way past even the most gargantuan defenders, came to be affectionately known as Little Bird. Eusébio, the Mozambique-Portuguese forward, renowned for his power shots and his bullet blasts through even the most formidable defences, was called The Black Panther; Gerd Müller, the forward of the German World Cup winning team of 1974, came to be known as The Bomber with his strange habit of scoring goals in a mid-fall or tumble, always under the steady gaze of the team’s cool and steady sweeper and captain, Franz Beckenbauer, respectfully referred to by friend and foe alike as The Kaiser.

Closer to home, Malaysia’s centre back Santokh Singh introduced a form of defence unique to the centre-back style — with both arms raised, swaying from left to right, it came to be known as the Bhangra defence, and at its finest moment, even eclipsed the rovings of a young Diego Maradona in a friendly match between the Selangor team and the visiting Argentine Boca Juniors team in 1981.

“Everything I know about morality and the obligations of men, I owe to football,” Albert Camus was believed to have said. A place of uncomplicated morality and of communion, the football pitch in the age of the beautiful game was a place for a transformative primordiality.

If there were a particular period in footballing history that marked a watershed from the Beautiful Game to the Technical Game, it would be following the World Cup of 1986.

Despite being hacked and chopped and fouled in every imaginable way, the beautiful Diego Maradona scored perhaps one of the most disputed goals of any tournament — the “Hand of God”. As if to vindicate himself, he set about then to weave, dance and turn through an entire hapless England team to score the “Goal of the Century”. As if to vindicate himself further, he did it again, to an equally hapless, helpless Belgium team in the very next semi-final match to push Argentina through to eventually win the World Cup of 1986.

By the 1990s, many of the rules of world football had been tightened, the age of camera replays introduced, the world of grace, caprice and chance eclipsed, ushering in the brutal world of the tactical football of touch-me-nots, in which the game finds itself digging even deeper today.

“Football is a pleasure that hurts,” Eduardo Galeano writes in the midst of all this; but still, with each game, there remains the deeper hope among the gallery for that runaway rebel, running against the script, that appeals to our deepest yearnings for a football, that still believes that the ball is indeed round, and that the world is at our feet.

This article first appeared on Aug 5, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.