The group exhibition comprises 12 artists who are collectively showcasing some 14 to 15 works (All Photos: A+ Works of Art)

This past month has seen the Malaysian arts community get more political than usual. In commemorating the anniversary of the 14th general election and its resulting historic change of government, it would seem the arts cannot help but to hold a mirror up to what that seismic political turn has led to, seeing the dust has now settled.

In the arena of visual arts in particular, A+ Works of Art’s Rasa Sayang exhibition is a survey within the fine art fraternity itself. The group exhibition comprises 12 artists who are collectively showcasing some 14 to 15 works.

Initially intended to reflect post-election perspectives, the curatorial process nevertheless led to the selection of artworks across a much longer timeframe — that of pre-May 9, its immediate aftermath and now, one year on.

Eric Goh, co-curator for the project, says Rasa Sayang presents its discourse through humour. “If you look at social media before and during the GE (general election), humour was used to criticise and satirise national issues. We too used the exhibition as a way of testing our hypothesis, to ask the question, ‘Is humour still relevant in today’s political climate?’ So, we invited artists to respond and contribute works, but then we realised that new questions were brought up — if humour is still relevant, who is being laughed at, and who is doing the laughing?”

You may not find that element of humour present as you walk through the gallery, or you may wonder what exactly is meant to be funny. But it is that lack of outright flippant humour or satire for the most part which lends a grounded sense of occasion to the exhibition, setting the tone for visitors to ruminate rather than just react.

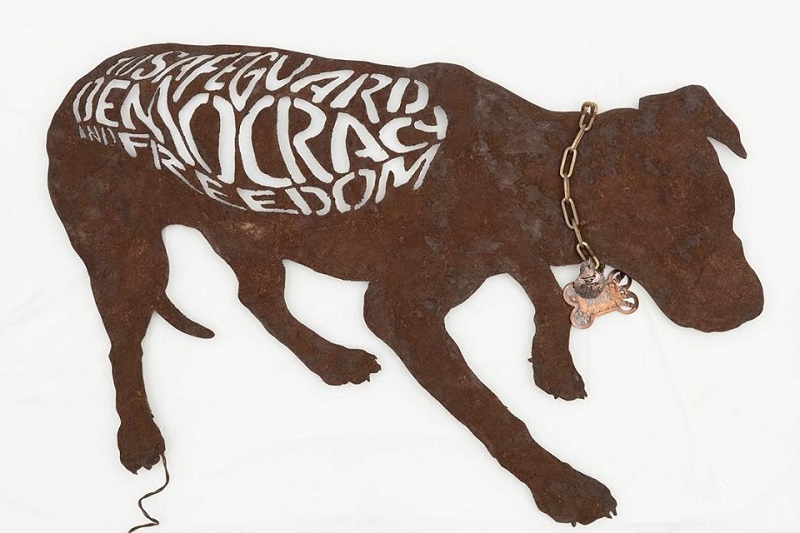

That said, a strong opening scene is always crucial — in Rasa Sayang, this comes in the form of Liew Kung Yu’s Run Dog Run (2018). Visible as a window display at the entrance of the gallery, the installation features seven dog sculptures cut from metal. Looking at it close-up reveals text cut-outs on the body of each dog, taken from the tenets of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) political party.

They include lines like “To safeguard democracy and freedom” and “Strive for equal status for all races in the country”. On each dog collar are pendants carved with their names, Chinese character initials that leave no doubt that they are taken from names of MCA’s top brass.

“It’s very loud and in your face, but it’s quite funny as well. Kung Yu created the work and brought some of these dogs along to political rallies in the run-up to the election last year,” explains Goh.

From that confrontational statement, the exhibition settles into a reflection on socio-politics, nation building and ultimately, the individual’s role — be it that of the viewer or the artist.

One would immediately notice, or rather hear, Okui Lala’s As If, Home (2015/2019), a video that audibly transforms the space into a construction site. The young artist from Penang is partially seen hammering, sawing and drilling throughout the video, working with a Bangladeshi builder named Mustafa. Visually straightforward, the contrast of their silent cooperation and the loud building noises nonetheless makes for a compelling watch.

Mustafa’s occasional muted instructions reveal that he is teaching Okui Lala how to build a house, and the thematic connotations of it all come to the surface quickly — that of nation building, of our need for these invisible migrant workers and with it, perhaps a mirror to our country’s own migrant roots.

“There’s also this class thing, about crossing class boundaries. It’s humbling, as if saying we share this house, so I should also learn to build it. There’s also the question of who is the original inhabitant of a newly built house? Because the workers often stay on site as they build,” notes Goh.

Similarly alluding to nation building is another evocative — if strange looking — display, Between Grey Area (2019) by Intan Rafiza. A ball of clay sits on the ground with a mass of string entangled all around it — they are remnants of a performance done during the launch of the exhibition.

At the time, attendees were invited to tie together cuts of string while Intan painstakingly moulded the large mound of clay. She then collected the tied strings and wrapped them around the clay as she continued to mould. She also walked around the room, ringing a bell every so often to symbolise awakening.

Known for her exploration of community bonds, Intan’s struggle with the moulding of the “tanah” is both physical and abstract, taking time and almost impossible to be done alone. The intertwined and embedded strings on the ball of clay are strangely evocative, as if a mess where one does not see where one begins and the other ends.

Going yet further into the politics of culture and heritage is Tan Zi Hao’s fabricated old manuscript, Kalau Kala Mengizinkan (2019). It challenges and illuminates the idea of heritage and culture.

“He plays with the word ‘kala’, which in Bahasa Malaysia refers to time. The text he created is that of a fictional Hindu god of time, and in the torn page — from a mock document — he argues about why the discovery of this rock should be preserved and included in our national heritage list,” says Goh. The work points out the contentious mindset of one culture being supreme over another, and the eliminating of history that is deemed as a threat.

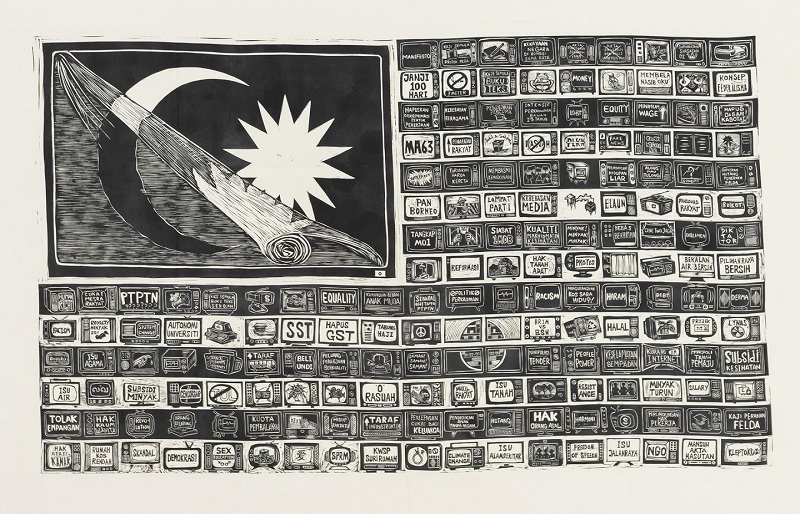

A more overt scrutiny of Malaysia Baru and the current government is Sabah collective Pangrok Sulap’s Siaran Ulangan (2019). The woodcut print features the motif of a Malaysian flag, where the stripes are made up of small TV boxes “broadcasting” key bread-and-butter issues of Malaysians, along with some of Pakatan Harapan’s election promises.

Effectively one big checklist of where we stand today — with issues that range from corruption to oil prices, national debt, freedom of the press and the review of school textbooks, to name but a few — one is welcome to review each and decide for themselves how far we have come along one year on, if at all.

On the other side of the gallery, Chang Yoong Chia’s Twin May Stories touches on the May 13 incident in 1969. Comprising two “stories” depicted in the style of an illustrated storybook, Chang draws inspiration from his recent residency in South Korea’s Gwangju area, where he learnt of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising that led to a brutal military crackdown. While it did not bring about reform, the incident was pivotal to the democratic history of South Korea.

Just behind it, on the wall, is Chong Kim Chiew’s mural painting of the Petronas logo in black, with trickles of “oil”. A symbol that represents a resource that signals economic wealth and even hope for any country — but also ties to global problems of kleptocracy, greed, power, environmental disasters and politics — the choice of rendering it in black begs the question, who is enriched in the end?

Accompanying the exhibition is a publication of essays and poems by local writers and researchers, which run the gamut of personal sentiments of what May 9, 2018, meant to them, to a spotlight on different communities — such as the urban professionals and the rural fishermen. Printed like a report, it offers a wider, if somewhat inconclusive, narrative of Malaysia now.

'Rasa Sayang', A+ Works of Art, ground floor of d6 Trade Centre, Jalan Sentul, KL. Until June 15. Tues-Sat, 12-7pm. Admission is free. Call (018) 333 3399 for more information.

This article first appeared on May 27, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.