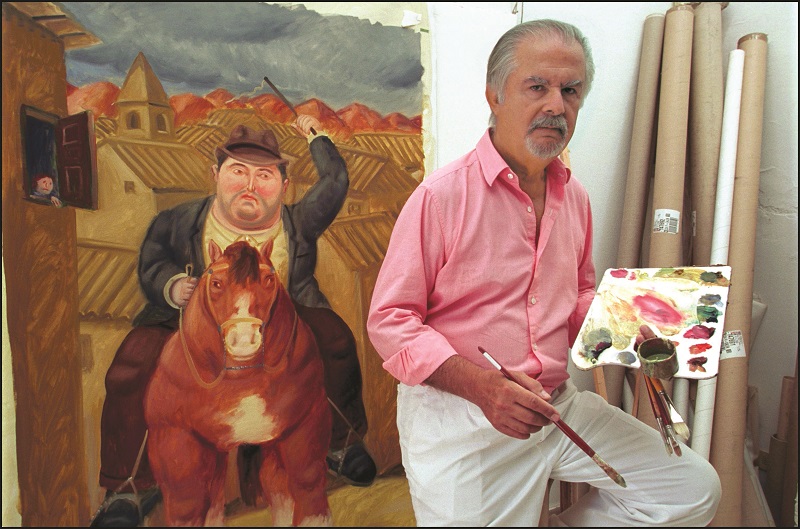

Fernando Botero Jr (Photo: Patrick Goh/The Edge)

Serendipity had a hand in shaping the Fernando Botero we know today. As his son tells it, the Colombian artist/sculptor’s life and work might have turned out differently if not for chance.

In 1950, with the 7,000 pesos he had won in a Bogotá art competition, Botero arrived in Madrid en route to Paris “to become the next Pablo Picasso”. Out walking one night, he saw a book in a bookstore window on Italian Renaissance master Piero Della Francesca. It was “the most interesting thing” he had ever seen.

“My father changed his mind about Paris and went to Florence to look at the great Renaissance painters,” says Fernando Botero Jr during a discussion titled Boterismo & The St Regis Kuala Lumpur: When Fine Art Meets Modern Legacy, hosted by the hotel on May 19.

“Who you choose to admire when you are young says a lot about how far you will go in life. My father chose Della Francesca, da Vinci and Michaelangelo and expanded his admiration to artists such as Picasso and Matisse. He always renders tribute to them and says, ‘I have never done a brushstroke that has not been authorised by the history of art’.”

How Botero found his unique style is again serendipitous. In 1956, he was among Latin American artists invited to Mexico by ailing painter Diego Rivera, who wanted to teach them the tradition of Mexican muralism. Assigned to paint a still life of a guitar, Botero ran to the flea market to get one but could only find the large acoustic bass guitarrón. He painted it and brought his work to Rivera.

For some reason, the young man had neglected to paint the small circle in the middle of the guitarrón. “Rivera took the brush from him and did a very small circle in the painting. All of a sudden, the instrument became huge and my father discovered his style. That was when Botero the artist, who conceives a world in which monumentality and volume are paramount, was born.”

Fernando says his father had the intelligence and foresight to realise that eureka moment. Once he started exaggerating volume in his figures and objects, he noticed people were attracted to them, an affirmation that he was on the right path.

Born in 1932 in Medellin — a provincial Colombian capital with no major tradition of art or culture — to a poor family, Botero had a natural talent for drawing and dreamt of being an artist. Between his first solo show in Bogota in 1951 and the major 2015/16 retrospective, Botero in China, is a body of work and a lifestime of stories that have inspired countless films and documentaries and more than 250 books and academic works in 40 languages.

“My father always thinks big and is a person of great conception. He is also a happy person who has a happy relationship with his [third] wife [Greek sculptor Sophia Vari] and a big family that adores him,” says Fernando, the eldest of Botero’s three children with first wife Gloria Zea, in a brief interview before the discussion.

Happiness guides Botero’s hands as he works with brush and bronze. He believes an artist’s work should give pleasure to viewers and speak directly to them without the need for explanation or interpretation. Pointing to the maestro’s Horse sculpture in St Regis’ Drawing Room, his proud son says: “Look at this — you feel its presence, and pleasure. It is so stunning, so beautiful and powerful. The same with his paintings.”

Who you choose to admire when you are young says a lot about how far you will go in life. My father chose Della Francesca, da Vinci and Michaelangelo and expanded his admiration to artists such as Picasso and Matisse

Botero, who starts the basic idea of every work with sketches, thousands of them, is also influenced by Mexico’s popular culture, evident from the strong, vibrant colours he uses. Once he decides on a subject matter, he rapidly expresses the sketch on canvas, with the basic outlines, forms and colours. Then he takes his time polishing the piece. “He may work two or three days, then stop and look at it again six months later. He can start a painting now and take 10 years to [complete it].”

Botero still paints and sculpts in his homes in Monaco, Italy and Greece, says Fernando, who goes around the world giving close to 70 lectures a year on the master’s work and his legacy. What set him on this circuitous journey was a question raised over lunch in Paris in 2008.

“I asked him: You’re almost 80 — is there anything missing in your life, anything you haven’t achieved? My father was silent for five seconds, then he said, ‘I can answer in only one word — China — the only major country where I have not had any opportunity to exhibit my work’.”

Thus, Fernando began working to take Botero to China. “It took us over seven years to make it happen and was incredibly difficult and complex. We had exhibitions at the National Museum of China in Beijing, the China Art Museum, Shanghai, and in Hong Kong [at the Central Harbourfront].” He was co-director of the Botero in China project, and his sister, Lina Botero Zea, curated the exhibits.

The Chinese response stunned him. “We had 1.5 million visitors, a number never ever associated with the world of art. After China, I decided to do this. There is tremendous interest in Botero today, increasingly so in Asia.”

Case in point: the commissioned 2.5-tonne Horse at St Regis KL, Malaysia’s first Botero sculpture and the largest he has ever made. The structure of the hotel was specifically designed to take its weight before it arrived in 2010.

Does what Fernando has committed himself to doing put him in his father’s shadow? “Fortunately I have my own tree, my own activities in my own life,” says the political science graduate from the Sorbonne in Paris, who did his master’s in public administration and MBA at Harvard University.

Fernando owns a health and beauty franchise business in Mexico, where he lives, and Colombia. He has been in politics, taught at university, written three books on Mexico and remains CEO of Estilo México, a magazine centred around the country.

“This is completely different from what I have done and I’m very happy to do it. My father is a great man and a great artist and being in his shadow is not a problem for me,” says Fernando, who never wanted to paint.

“They say this type of genius skips one or two generations. Hopefully one of my grandchildren will be talented,” adds the father of three.

This article first appeared on June 4, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.