Chipta 11a’s grilled aka ebi with belacan vinaigrette (Photo: Chipta 11a)

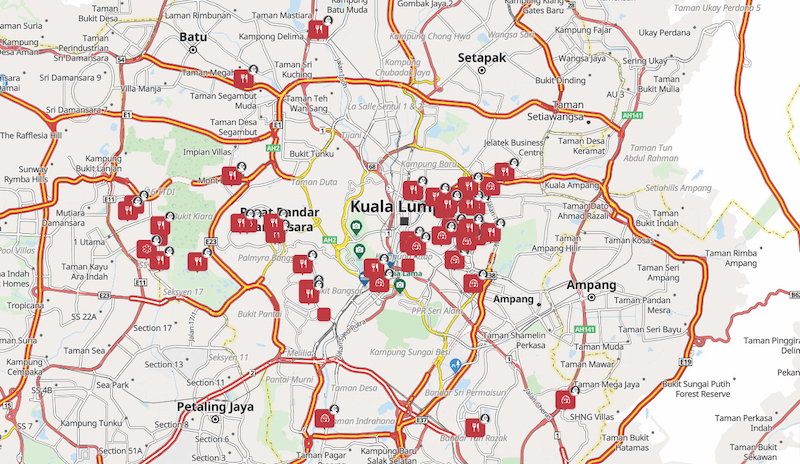

When you have a minute, please browse the website ViaMichelin.com. Click on the red fork and knife icon, type in “Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia” and click search. Then have a look at the map of Michelin-recommended establishments as represented by the icons. Do you notice something?

There seems to be a force field running north-south along Jalan Tun Razak. Of the 57 listed KL eateries, only three lie east of the force field, one of which is evergreen stalwart Cilantro and the other, Roti d’Tandoor, which was added to the Michelin Guide last month.

kl_map_2.jpg

It begs the question: Why? There are some amazing places to eat east of the Golden Triangle. If you are thinking of char siew (and I think about it all the time), Char Siew Yoong in Cheras and Soo Kee in Ampang immediately come to mind. But both are in the eastern wastelands, forgotten to all except the hordes of KLites and local, Singaporean and Indonesian tourists who try their luck at getting tables at these institutions of deliciousness.

There is another Michelin force field in play, of course, and this one runs around the boundary of KL. Not many realise this, but Michelin’s present purview only falls within the boundaries of the city, ignoring the incredible degree of economic, social and cultural connectivity and integration between KL and the rest of the Klang Valley.

I find this partition startling for practical and historical reasons. Practical because few, if any, locals pay heed to the boundaries. And historical because you cannot really talk about the rise of KL without mentioning the critical role of the Klang Valley cities and settlements in its development. In short, KL and its food scene evolved the way it did only because the Klang Valley enabled it. Treating the city as a culinary destination on its own sans the Klang Valley is seeing only one side of a coin. How can we even pretend to have a legitimate conversation about the best satay and bak kut teh, two of our iconic Malaysian dishes for example, when eateries in Kajang and Klang cannot even be considered?

soo_kee.jpg

It is utter travesty that Singapore, a city state whose inhabitants (well, the reasonable ones) readily concede the superiority of Malaysian street food over their own, had 17 hawker Bib Gourmands and two hawker stars in its inaugural Michelin Guide 2016. The very limited area of KL that Michelin deigned to inspect, on the other hand, could manage only 15 Bibs in total, many of which do not in fact represent our strong and historic street food culture at all (Aliyaa, Dancing Fish, Sao Nam and De.Wan, to name a few).

This is not the fault of KL’s street food vendors, but the structural problem of Michelin somehow ignoring eastern KL and the heartlands that are home to a fifth of the nation’s population. And I have a huge problem with this personally because Michelin awards drive significant custom and promotional opportunities — see the Gastromonth promotion that ran in May, for example, which was open only to Michelin-selected restaurants. There are people’s livelihoods at stake. I do not think it is fair that a small business suffers simply because a competitor had the good fortune of a Michelin inspector walking in, and not because the inspector made a judgement on which was better.

kompassion.jpg

It isn’t just the street food scene that suffers from this arbitrary partition. There are also excellent restaurants that missed out simply because they are not within the dividing line of KL. Who would argue, for example, that Jack Weldie’s ingenious fusion of indigenous Malaysian and Japanese flavours at Taman Paramount’s Chipta 11a in Petaling Jaya does not deserve at least a select? Or that Damansara Kim’s Kompassion, recently recognised by the Thai government for upholding the reputation of authentic Thai cuisine overseas, was omitted simply because it is literally 450m on the wrong side of the tracks? What about Chef Chew Kitchen, the legendary dai chow in PJ’s Section 19 that does around four turns a night, catering to diners clamouring for its iconic claypot kampung chicken rice and old school sweet and sour pork served on ice?

The solution? Apart from mustering up the courage to cross Jalan Tun Razak into Mordor, Michelin has to expand its coverage into the Klang Valley. And fast. There may of course be a legitimate reason it will not do so (most likely to do with funds) but Michelin needs to realise that its KL Guide currently paints an incomplete and distorted picture of the multifaceted richness of our local cuisine. And that should be of massive concern to our tourism authorities because, let’s be frank, the vast majority of foodie tourists visiting Malaysia are coming for the food that delights us all and which has made us famous. By which we do not mean pseudo-European fine dining or thousand-ringgit-a-pop Japanese omakase meals.

This article first appeared on Aug 14, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.