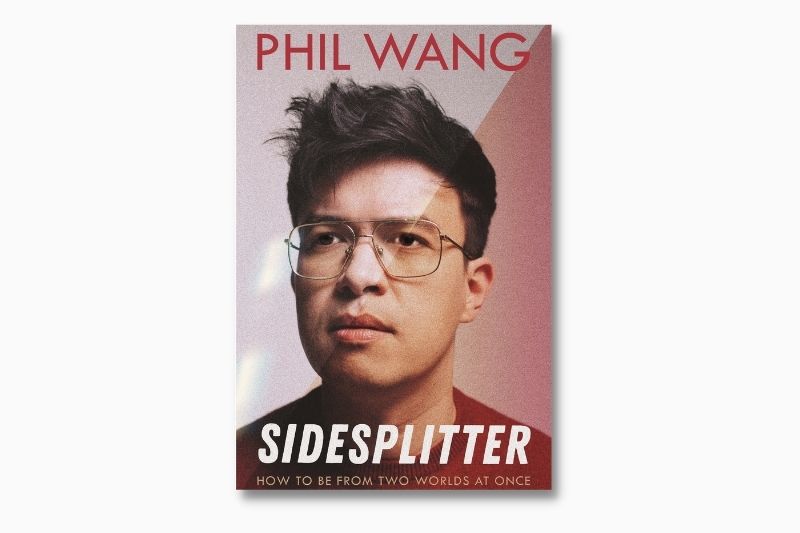

Alienation and assimilation inform his acts, where he stands tall as a Eurasian male who will not be made fun of but can laugh at himself (Photo: Matt Stonge)

Comedy is a science for Phil Wang, who uses the mechanics of what he learnt in engineering to frame his stand-up material. “Fundamentally, comedy is about building a logical pattern and then breaking it. The setup is logical and the punchline is illogical, within a logical framework,” he says.

“I can recognise the pieces of structure, which bits [serve] which purpose, the missing component you need to design and fit in. I’ve learnt how comedy works, to a certain extent.”

Wang does not consider himself inherently funny, the way a clown is. Comedy is innate or it can be learnt, he thinks. “I am more learnt than innate. For me, it is always an intellectual exercise. It’s quite scientific.”

Then again, there is comedy in the blood of this 31-year-old born in Stoke-on-Trent to an English archaeologist and a Chinese-Malaysian civil engineer. Grandad Gordon — “the first joke teller I ever met” — always had a few gags saved up to delight them when they visited. Some were over Wang’s head, but “jokes as an idea and sentences created just to elicit laughter” awed and excited him.

Three weeks after his birth, baby Phil was brought back to Kota Kinabalu because dad’s five-week leave had run out. The first of three children, he grew up in Sabah until the age of 16, when the family moved to Bath. The UK has been home since, although people who meet this six-foot-one Eurasian always ask, “But where are you really from?” It is a question Wang often asks himself too, and he hopes writing Sidesplitter: How To Be From Two Worlds At Once will bring him clarity.

The September release is a collection of humorous, and intelligent, essays about being mixed-race and part memoir, written in 10 themed chapters: Family, Words, Food, Race, Comedy, Love, History, Assimilation, Nature and Home.

Family, on dad’s side, comprises five uncles, five aunts and 10 cousins glued by Shorinji Kempo, a Japanese variation of Shaolin Kungfu. In fact, the author’s parents met at the dojo. Madeleine Piper, who came to Malaysia under the Voluntary Service Overseas, had signed up for martial arts classes and Benny Wang was her instructor.

Gong Gong (Wang Yap Kong), an on-the-run communist who found peace in Sabah and became the town barber, and Po Po (Sanoh Lukim), a Kadazan-Dusun orphan, had both died before any of Wang’s generation was born. But they remained a lingering presence throughout his childhood and are honoured by the noisy, close-knit brood every Qingming festival.

phil_wang_sidesplitter.jpg

“In Asia, your family is your social life,” he writes, unlike in the UK, where “the family is a nest to be flown”.

Moving to Bath heightened the humming sense of alienation he had felt the entire time he was in Malaysia, more so because the inherent teenage experience is awkward and alienating, Wang says. Being in a completely new culture and society on the other side of the world made it worse.

Things improved when he entered Cambridge and found himself among people who had also been taken out of their comfort zones. Adulthood saw him coming into himself and stand-up became a form of self-therapy, “a way out of social anxiety”, says this comic, who won the university’s Chortle Student Comedy Award as a sophomore and became president of Cambridge Footlights, the student comedy society, in his final year.

Malaysia figures in his chapters on Words (speaking proper English at home and Manglish with his friends, and learning Malay and Mandarin in school); Food (it is the national pride and pastime and the purpose and point of every day, compared with having a functional value in the UK); History (the reach of the British Empire); and Race (looking different, being treated different and dealing with that using comedy).

“I find discussions about race enlightening, important and, on occasion, funny,” Wang says. Alienation and assimilation inform his acts, where he stands tall as a Eurasian male who will not be made fun of but can laugh at himself.

“I think self-deprecation shows an audience you are aware of yourself and your flaws. That is very important, too, for a comedian because it means they see things clearly and objectively.

“But East Asian men are already so deprecated and so emasculated in Western popular culture that I thought perhaps it might be more interesting to be confident, and high-status. Because of that, I have become less and less self-deprecating as I get older. That’s not to say from time to time I won’t take a dig at myself.”

He does, at international comedy festivals and shows. Wang has written and starred in Wangsplaining, his own Radio 4 special on BBC. In Philly Philly Wang Wang, a Netflix special recorded at the London Palladium, he draws laughter by exploring race, romance, politics and his British-Malaysian heritage. He has appeared in Live at the Apollo, Have I Got News for You and Roast Battle.

The need to tell about his Asian world is also a reflection of maturity. “In your youth, you’re trying to fit in so much, you reject or put aside your personal history. As you get older, you feel more confident about your place in life and society, and you feel more comfortable talking about the stuff that makes you different or weird. This book is me hitting that stage of my life where I feel at ease enough telling people about this aspect of my life that they might find alien and boring.”

Doing that is no laughing matter, though. Wang’s first thought when he decided to write Sidesplitter was: How am I going to describe Malaysia, a very unique place that is so alien to a lot of people? How am I going to describe a man dressed as a KFC chicken, or a coffee shop? How am I going to explain what lah means. I think I did it all right. People seem to be getting the idea.”

The discipline of putting something on a blank page was hard, but he enjoyed the editing. “Every time you decide to write something, you are rejecting an infinite universe of other possibilities. Once things are down, I like working at them because there’s a framework. I enjoy going back through things, tweaking them and making a sentence as good as [it] can be.”

The same goes for practice: He used to pace around his home with hairbrush in hand to rehearse for shows. Nowadays, jokes pop up as punchlines in his head and he works on them backwards, later on. Some come fully formed; some take months and months. A phrase in a podcast might spark an idea. Ideas could surface when he is in the shower, on trains, or “out consuming life as much as you can and interacting with people”.

The last was why Wang found writing comedy difficult during the pandemic. “You weren’t having conversations with people or going out in the world to encounter the random events of life. The first lockdown was quite frightening because I was trapped in a flat in the middle of London — I started to feel boxed in.”

Working on his book, playing chess online, reading, watching a lot of films, listening to the BBC World Service and Radio 4 and doing a couple of Zoom gigs helped lift the gloom. He is rereading Sidesplitter “to check for any more mistakes”, he says with a chortle, and reading a book about wine to prepare for a quiz show on the subject.

An introvert by nature, Wang recharges by being alone. “I enjoy being with people but I get tired and need to be on my own to recuperate. I think extroverts get tired being on their own and they go and spend time with friends to recover. That’s not me.”

Neither is he a laugh a minute at social gatherings. “When people don’t know me well, they think I am going to be funny. I rarely am. I’m quite serious in person.”

Stand-up is a different party animal, altogether. Wang says he will always do comedy as it gives him a sense of purpose. He will stick to his own script too, because “stand-up is so personal and so much about my thoughts and how I see the world. It’s so private, I can’t see me enjoying it if it’s someone else’s words”.

The first stand-up comedian he became aware and watched a lot of was Russell Peters. “He talked about Asians and all kinds of races and made fun of their cultural differences — that really got me.” Dave Chapelle, who spoke fearlessly about race, was another influence when Wang discovered stand-up. There was also The Simpsons while growing up. “The show informed a lot of my generation’s sense of humour because it is both absurd and very smart. That’s my dream, that’s what I am trying to do.”

Comedy does not get easier with experience, for him. “I’m still nervous before a show and I think that’s good. The worst performances I have given have been when I was the least nervous, when I had been complacent or not worried about it. I’ve gone up and been bad because I didn’t have the nervous energy, I didn’t get the adrenaline and my mind didn’t work as well.”

Going on stage is essentially entering into a flight or fight response situation, he reckons. A good comedian decides to fight every single time. “It’s that energy of deciding to fight that makes you sharp and funny and quick. I need to be nervous, at least a little bit. I’ve shortened the amount of time I’m nervous to, like, the two minutes before I go on stage.”

Is there any other job harder than trying to make a roomful of people laugh? “Yes, I’d say working in an emergency ward or being a rubbish man or a soldier.” Then again, “You have firefighters coming up after a show and saying, ‘I couldn’t do what you did’. You think, really?

“Public speaking ranks really highly among people’s fears. It’s the worst fear and that, I think, is what makes stand-ups skilled professionals because we can overcome this fear that most people cannot.”

Wang describes his humour as “quite dry and very precise. But now, I am trying a bit more silliness. I’m trying to make it a little more goofy, a little bit more physical. Why? Because I have run out of jokes, essentially, and I think it is a good skill to have. It’s an untapped potential for me. I used to be quite clownish as a kid; I made a lot of funny faces, that sort of thing. I want to bring that back again”.

He sees Malaysian humour as really sarcastic, quite dry and very self-deprecating as a nation. “The British like to say they like to make fun of themselves, which I don’t think is true. I think they make fun of themselves as individuals, about this idea of Britishness. Malaysians are quite respectful to each other as individuals but like to make fun of Malaysians as a whole. So you end up with shows like Phua Chu Kang and Kopitiam, and Instant Café. These great comedies are about a whole culture.”

No subject is taboo for Wang if he finds it interesting and feels he knows enough about it to make an informed point. “The things I always love talking about are race, culture, history, China and the Chinese. Now I am talking more about politics — like race dynamics and sexual politics — as it has become more enmeshed with popular culture.”

On what makes him laugh out loud, he says: “I have quite a dark sense of humour. If something sunny suddenly gets very dark, that makes me laugh — which does not always make me look good. It makes me look insensitive. I maintain that laughing about something does not diminish it. You can laugh at something for various reasons. And silliness — I will always find well-performed silliness funny.”

People being really honest about their flaws makes him guffaw too. “This is something we have lost touch with in this time we’re living through, when everyone has to pretend to be these morally perfect beings, on pain of social rejection or ostracism or, in some cases, even losing their job. When someone is honest about their mistakes or things they get wrong, they are vulnerable. Yes, when someone admits to moral failure, that always makes me laugh.”

What does he do when he thinks something is funny but the audience does not? “I usually say, ‘That one is for me’, and then move on. I probably won’t do it again. Or, if only three people per night laugh at a joke but they laugh very loudly, I’ll keep it, but keep it short.”

After years on the comedy circuit, he is still surprised how many people cannot take a joke for what it is. He finds people’s sense of humour quite conditional — they will laugh, until something important to them is made fun of. And comedy has become quite conflated with politics, he thinks, and it has itself to blame for this.

“Comedy started to believe in its ability to change the world too much, especially over the Trump years. It became quite fashionable for comedy to be quite righteous politically and to campaign and call for a change in society. I don’t think comedy has any place to do that.

“Once you conflate comedy with earnest political activism, you invite people to interpret your comedy as what you really believe. It’s no surprise then that people will take offence at something that was intended to be a joke because comedy as an industry has earnestly invited people to take it seriously.

“I don’t believe comedy can change the world — it’s a rebellious thought. What changes the world is earnest hard work, really hard work and commitment to difficult jobs — research, politics, medicine, science. Comedy can give people relief and a new perspective on things. It needs to be honest with itself about its purpose. Only then will audiences start to perceive comedy for what it is.”

Honestly, humour and tears can work together. In 2019, after a sold-out run at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Wang spent Christmas in Malaysia for a big family reunion and a wedding. Life was good and, over the years, coming back had begun to feel like “a backwards step to a part of my life I was done with”.

He upgraded his return ticket to business class on frequent flyer points and, as everyone talked about plans for the New Year, announced he had to be back in the UK. Seated in his private pod by the window, “I’m handed a glass of champagne, the plane takes off and I cry all the way to London”.

It is difficult to get people’s sympathy when you are in business class, Wang says. But crying with champagne in hand was meant to “represent where I was and all the pretensions I had taken on and the cost of it and what I’d lost without realising it.

“The image was potent and completely real as well. It was sort of like my position — even when life seems to be essentially fine, you can find yourself in this very sad place,” he adds of the final punchline in Home, the chapter that closes Sidesplitter.

Purchase 'Sidesplitter: How To Be From Two Worlds At Once' at Kinokuniya for RM99.90 here.

This article first appeared on Nov 1, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.