England’s Luke Shaw and Kalvin Phillips console Bukayo Saka after the penalty shoot-out (All photos: Reuters)

Even for a game never too shy to show its messianic streak, it was a lofty ambition. Just as flood follows drought and feast follows famine, football’s UEFA 2020 European Championships was meant to symbolise mankind’s recovery from the plague. Although that became an impossible mission, after a year and a half of fear and isolation, it still delivered a (mostly) wonderful distraction.

Football, of course, had continued through much of that time — one of the few things that had — but without fans, it was a sad and pale imitation kept alive on an intravenous drip of broadcasting rights. However, for a mad month across Europe, ghost games gave way to limited crowds and the excited few made up for the missing many.

Players responded to the mood swing and a football feast ensued. Successful nations were gripped by a festive atmosphere as lockdowns in the 11 host nations were gradually lifted. And for finalists Italy and England, bad times had never seemed so good. Well, until a very bitter end for England, anyway.

The two were the most severely affected nations in Europe when the pandemic struck. Italy was on the front line, but Britain soon caught up with its mishandling of the outbreak, only partly redeemed by a swift vaccine rollout. The Italians, a tactile people with an ageing population, were in despair and see the football triumph as a healer for the nation.

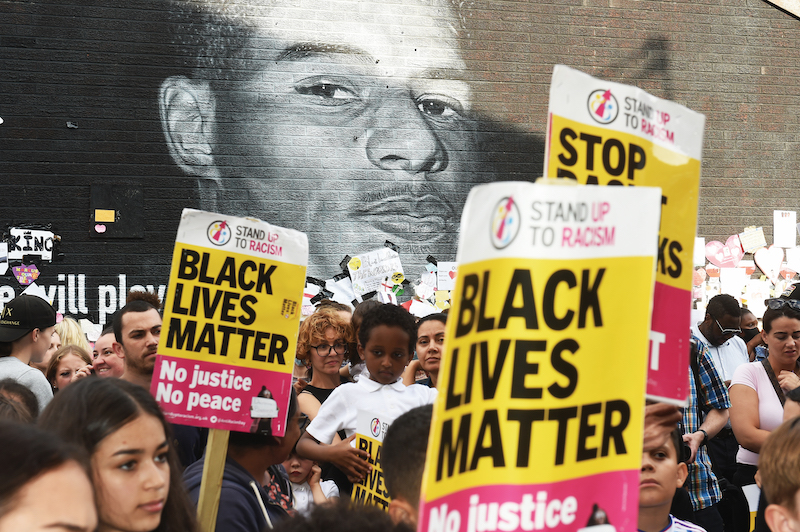

England, alas, saw old wounds reopen, with a defeat on penalties causing racism and violence to rear their ugly heads. Racism hit a new low when the three non-white players who failed in the shoot-out were singled out for special treatment. “Jet fuel to the worst people on the planet” is how author Matt Haig described it.

2021-07-13t173946z_1499903132_up1eh7d1d26ku_rtrmadp_3_soccer-euro-eng-rashford.jpg

It was all the more galling for a likeable, diverse squad whose keen social awareness had finally won over many sceptical fans of Asian, African or Caribbean backgrounds. Taking the knee was the most visible of many acts that included donating a sizeable chunk of their prize money to health service workers.

Among them was Marcus Rashford, who had run rings around British Prime Minister Boris Johnson with his school meals campaign. A mural to his achievement in his home city of Manchester was defaced, bringing him, he admitted, “to the verge of tears”. England manager Gareth Southgate called the abuse “unforgivable”, adding, “It’s not what we stand for. We have been a beacon of light in bringing people together.”

As gut-wrenching as the racism was, it struck a particular chord with the rest of the population, especially in such trying circumstances and many rallied to support the players. It can only be hoped that with such a harsh beam highlighting how repugnant this prehistoric cancer is in today’s society, it may shame the social media companies into action. But no one is holding their breath.

Only a game? Football’s importance has been famously exaggerated. And it does sometimes think it’s the saviour of mankind. It carries on during a pandemic, continues to spend during a financial crisis. But the formation of the European Super League was a response by rich clubs to a perceived slackening of interest, namely falling viewing figures for the Champions League.

But the greed of rich owners is one of the fans’ biggest gripes. Others include a feeling of neglect over ticket prices, kick-off times, VAR (video assistant referee) and rules invented by the Politburo and implemented by the Waffen-SS. An oft-quoted phrase by fans of a certain age is, “The game has gone.”

But in recent weeks, the game has come back. Interest levels soared to heights that only billionaires in rocket planes can reach: uniting divided populations, boosting economies and, at least to the converted, raising the spirits of tens of millions way beyond Europe’s borders.

Despite the inconvenient time, it is credited with giving a lift to China’s night-time economy, making Southgate more popular than Winston Churchill and being seen as a blessing by Italy’s largely Catholic population. Italians refer to their Holy Trinity as “God, family and football”, and when they speak of “the apocalypse”, they don’t mean the pandemic, but failure to qualify for the 2018 World Cup.

Just as football needed the Euros, Europe needed football. Starved of excitement for so long, fans and even those not so interested leapt on the bandwagon to fill the void. In turn, the game responded with one of the best tournaments since the 1970 World Cup. And it demonstrated its enduring appeal well beyond the touchline.

Although there’s a growing hunger among fans eager to return, there is concern whether the game can keep them once the novelty wears off. The existential threat is from the younger generation who had been watching only highlights, if at all. And it is why Juventus president Andrea Agnelli proposed that broadcasters come up with a package of the last 10 minutes of games to tempt Gen Z. The hope now is that Euro 2020 may have stretched those attention spans.

One of the tournament’s fundamental flaws was the multiple hosting, which UEFA president Aleksandar Ceferin says will not be repeated. It was unfair to send Switzerland travelling 15,485km while Scotland did only 1,108km and England played six out of seven matches at home.

But the full cost of this crackpot scheme has yet to be felt. In England as the climax drew closer, caution was thrown to the wind. UEFA’s VIPs were allowed in and fans made the most of a final appearance by England that, after a 55-year interval, is only slightly more frequent than a visit from Halley’s Comet. The occasion took precedence even over personal safety.

Whether the game has come back to stay is open for debate, but this will have helped. It was the most fun since Covid-19 turned up and a reminder that there’s no substitute for the real thing. Only a game? Only football could have had this kind of effect on people.

This article first appeared on Jul 19, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.