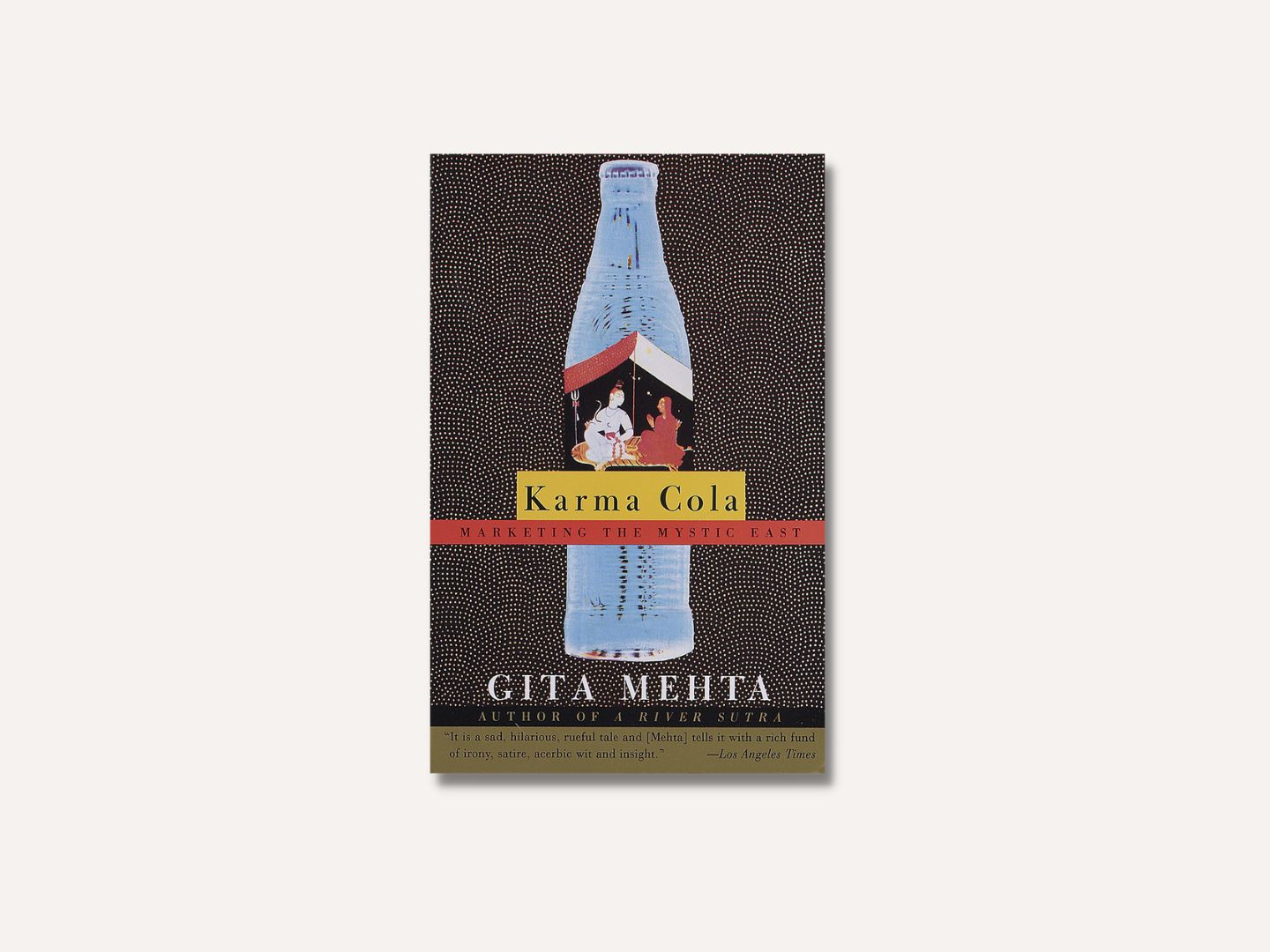

Karma Cola, her seminal work first published in 1979 — a mix of journalism, social commentary and storytelling — immediately put her on the world stage (Photo: Penguin Random House)

Gita Mehta, the eminent writer and documentary filmmaker who was equally at home in the US and India, passed away in New Delhi on Sept 16. During her 80 years, she wasn’t as prolific as other writers. She didn’t publish many books but Karma Cola, her seminal work first published in 1979 — a mix of journalism, social commentary and storytelling — immediately put her on the world stage. It called out the performative dissonance of the hippie movement, as Gita wrote in Karma Cola: “The seduction lay in the chaos. They thought they were simple. We thought they were neon. They thought we were profound. We knew we were provincial. Everybody thought everybody else was ridiculously exotic and everybody got it wrong.”

I remember reading Karma Cola five years after its publication. I was a student of English Literature at the University of Delhi’s Lady Shri Ram College at that time, but despite this hallowed institution being a bastion of feminism and political advocacy (Aung San Suu Kyi is an alumnus), the texts we read in class were mostly by dead, white, British men: Wordsworth, Dickens and Chaucer, with a sprinkling of female voices like Bronte and Eyre.

It felt liberating to hold in my teenaged hands the voice of an Indian woman who was not only an incisive observer of Indian society, but also one who delved deep into the hollowness of global consumerism with wit and intelligence. Here was a woman at home in the world, yet so articulately rooted. “The assault on the senses. The caress of the senses. Surely God made India at his leisure,” she wrote in Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of Modern India. After her death, William Dalrymple would write on Twitter, referring to Gita and her husband Sunny Mehta as “the very definition of cosmopolitan Indian brilliance, intelligence and elegance on the world stage”.

gita_mehta_books.png

Gita was born into privilege. She was the daughter of Biju Patnaik, Indian independence activist and former chief minister of Odisha, and the elder sister of Naveen Patnaik, the current chief minister of Odisha. She was married to American publisher Sonny Mehta and lived between continents, spending time every year in India, whether in Delhi or Odisha, or shooting documentaries around the world. Dateline Bangladesh is a documentary that is still accessible online, offering one a searing look at the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Although Gita’s own politics was complicated by her familial connection to the ruling party in Odisha — she turned down a Padma Shri award in 2019, saying, “I am deeply honoured that the Government of India should think me worthy of a Padma Shri but with great regret I feel I must decline as there is a general election looming and the timing of the award might be misconstrued, causing embarrassment both to the Government and myself, which I would much regret.” Dateline Bangladesh pulls no punches.

She captures the desolation of a country waging war for a long nine months and the human price paid for liberation, using Bengali nationalistic songs as well as Urdu ghazals to supplement her English commentary. Towards the end of the documentary, she fiercely intones: “A hundred and thirty-two nations subscribe to the United Nations, to its ideals of justice and human worth, its pledge to redeem mankind from the scourge of war, and through the long months, 132 nations stood silent.”

Gita produced and directed at least 14 TV documentaries for UK, European and US networks, connecting a world that was multilingual and multifaceted. She will be remembered through her books — Karma Cola (1979), A River Sutra (1993), Raj (2007) and Eternal Ganesha (2010) — but, for me, she will always be the writer who dazzled with a book that took on global issues within an Indian setting, and spoke from a perspective that was so clearly Asian. She showed me how to feel deeply, love intensely and still not lose the critical perspective. As Indian politics marches towards an India that feels increasingly theocratic and monocultural, her voice, at home in a secular world, will be much missed.

This article first appeared on Sept 25, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.