Hublot recently launched the all-titanium Classic Fusion Chronograph Shepard Fairey, limited to 50 pieces (All photos: Hublot)

It started as a joke. And really, it should have ended there, but this joke had no discernible punchline, no full-stop to cue laughter, so it just kept rolling and rolling. Until it grew into an entire movement, spanning an anthem of anti-authoritarianism, an image of dissent, a philosophical puzzle, and even a clothing line.

Thirty years later, it is still going.

Shepard Fairey was in the last of his teenaged years in 1989 when he created the “André the Giant has a Posse” stickers and posters that would launch him to street art fame. He describes it as a “spontaneous, happy accident” while teaching a friend to make stencils during their time at the Rhode Island School of Design. He was flipping through a newspaper for an image to use and happened upon a wrestling ad featuring André the Giant. The friend turned down the image, but Fairey found it funny, created the stencil and stickers, and distributed it to his own “posse”. Within the next decade, thousands of such stickers were photocopied and hand-silkscreened for display worldwide, and an eponymous documentary made to chronicle the now-influential street art campaign was screened at the 1997 Sundance Film Festival.

The campaign was forced to go through a rebranding exercise when Titan Sports Inc threatened Fairey with a lawsuit for unlicensed use of its trademarked André the Giant image. The artist reimagined the wrestler’s face and built the Obey Giant brand around it, not only as a parody of propaganda but also as a direct tribute to the “Obey” signs that peppered the 1988 cult movie They Live.

So, what exactly was the joke? As it turns out, it lies in the fact that there wasn’t one. The phrase originally had no significance or hidden depth. It was merely intended to inspire curiosity and elicit a reaction, mostly among audiences who are convinced that everything has meaning and who struggle to analyse these two arbitrarily paired words, sometimes giving up and condemning what they don’t understand as vandalism or cultic. Those familiar with the story behind the sticker are tickled pink by this outrage — the very ambiguity that frustrates the unaware is adored by those who are in on the joke.

hublot_ambassador_shepard_fairey_wearing_the_classic_fusion_chronograph_shepard_fairey_19.jpg

“That’s exactly the point,” says Fairey when we meet on Zoom. Despite his numerous talents — he’s a painter, graphic designer, DJ, illustrator, street artist, skateboarder, founder of OBEY Clothing and co-founder of advertising agency Studio Number One — a slash of reserve underlines his friendliness and he seems almost shy. “The stickers were an absurd joke but I liked how it disrupted what people usually saw in a public space, typically occupied by advertising or government signage. The idea that an individual could enter the conversation made people think about who has control over these public spaces. They not only noticed the stickers, but tried to investigate what it meant.

“And when you add a loaded word like ‘obey’, which represents different things to different people, it made them confront how they felt about the suggestion of obedience, even if they didn’t know to what,” he continues. “The real goal was to encourage people to be more analytical, to decide what they will consciously submit to or agree with. Most of the time, obedience is something quietly imposed on the public by people who want to be a sort of invisible hand. They want to encourage you to do what they want without realising it. The idea was to get people thinking about this in everything they encountered, not just my art. It works on some people, others just get mad.”

The right motifs

While art for the masses is his mainstay, Fairey occasionally rubs shoulders with the luxury sphere and refuses to apologise for it. And there are critics who demand remorse for these apparent breaches, as though he has no right to more profitable bread-and-butter projects or is confined to a particular genre or price point. The notion holds even less water in this context, with Fairey’s work featured in the collections of world-renowned institutions such as The Smithsonian, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The man is bound to be expensive.

“Anytime I do something luxury, I am attacked for it,” he shrugs. “I am still an artist for the people, I make very affordable things, offer free downloads for a lot of my work, and ensure my work is very affordable. But I also do very pricey paintings. And while I’m not a flashy person, I love watches, and nobody in the luxury watch space does artistic collaborations as meaningfully as Hublot.”

The new Classic Fusion Chronograph Shepard Fairey is his sophomore collaboration with the Swiss watchmaker, comprising a 45mm all-titanium timepiece with a mandala symbol brushed and engraved across the dial and bezel. Fine skeletonisation of the dial reveals glimpses of the self-winding Calibre HUB1155, developed in-house with 42 hours of autonomy. The hands display Fairey’s signature “Star Gear” mark and a lined black rubber strap completes the construction. A portion of the proceeds from this 50-piece limited-edition watch will be channelled towards Amnesty International to support its campaigns against human rights violations.

shepard_watch.jpg

“I was drawn to the artistry and quality of Hublot, and working on a watch that is really an art piece in and of itself was an exciting opportunity,” says Fairey, who is fastidiously discriminating when it comes to partnerships. “Hublot’s watches have many beautiful elements working harmoniously within a circular dial, visually similar to the mandala. It symbolises harmony and wholeness, values that echo the mission of Amnesty. I often use mandalas in my art so there’s a natural connection to my work, but it also gives Hublot fans a good introduction to what I do. I love these possibilities for organic cross-pollination in collaborations.”

Meanwhile, the charity component resonates and aligns with Fairey’s consistent activism over the decades, as he championed causes from environmentalism to social justice. “I try to be informed. I read a good deal, pay attention to the news, and research the root causes and potential solutions, whether it’s about climate change or the homeless problem in Los Angeles,” he says. “I try to go beyond the talking points of people with an agenda on either side so I can communicate about the subject in a way I can stand behind intelligently. I also try to partner with people who are taking the best actions on these issues. I’ve worked with the Southern Poverty Law Centre and Equal Justice Initiative for Black Lives Matter, for instance. My philosophy about being a global citizen is to get people to think not as nationalists, but about the fact that we share this planet and need to respect and protect it and each other.”

Anarchy need not be aggressive

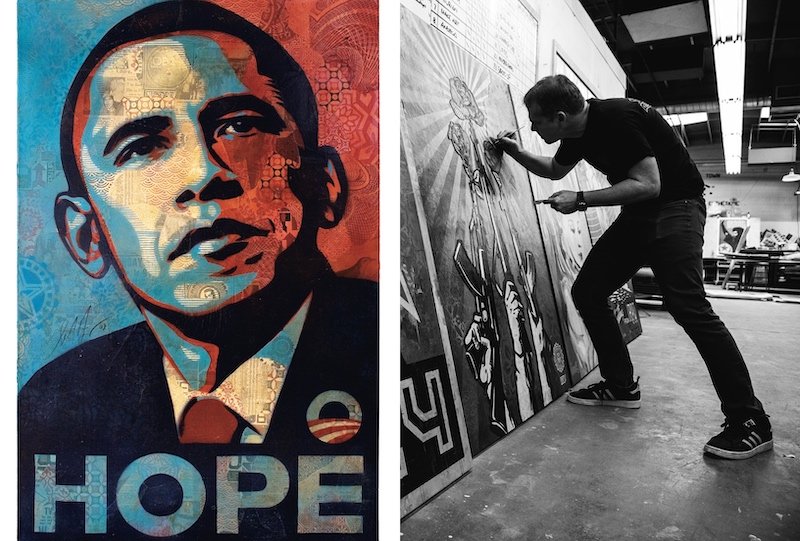

Bob Marley, The Clash, Public Enemy and Dead Kennedys not only influenced Fairey’s ideas of social justice through their music, but also taught him about the insertion of social and political commentary into art. Participating in these conversations pushes Fairey to examine his own stances or political inclinations, leading to pieces such as the “Liberté, égalité, fraternité”, created as a symbol of hope for France after the 2015 terrorist attacks, or his iconic “Obama Hope” poster in conjunction with Barak Obama’s 2008 electoral campaign.

The Obama poster was mired in controversy — the portrait he used was an uncredited Associated Press photo that led to copyright challenges — and Fairey later expressed disappointment in the administration for “drones and domestic spying” among others in an interview with Esquire. Despite his disillusionment, he still advocates for political awareness and involvement.

“Yeah, I’m not a big fan of bureaucracy but I can tell you: I have more faith in a bureaucracy that is democratically elected and is in some ways accountable to the people than I do in private-for-profit businesses. Making governments more accountable is something I’ll always push for, but working directly with the administration or politicians can be ineffective, so it’s important to work outside the system too. It’s what I call an inside-outside strategy. I am actually willing to wear different hats as needed to get the work done, even if it’s not good for my ‘outsider’ image. I still think like it outsider, but I’m willing to deal with bureaucracy to make it better. Working on campaigns like encouraging voter turnout this last election or financial reforms that will restrict the influence of corporations over politicians is me doing my part to seek remedies.”

fairy_obama.jpg

The resolve deepened when Obama’s successor took over. The Donald Trump years were a blight, which Fairey describes as four years of living under a black cloud. “This might sound really crude, but I saw him as the pimple, not the underlying bacteria; he was the symptom of the disease. He made things worse, he fed the bacteria, but it pre-dates him and was what allowed him to happen,” shares the designer. “It really shows how leadership and compelling stories around good values is necessary to keep the demagogues at bay. In On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, author Timothy Snyder discusses the variables that led to various fascist regimes: Mussolini, Hitler, Franco. And you saw every single one of those elements either being exploited or cultivated or both by Trump.”

That said, the Trump era proved to be perfect fodder for creativity, leading to the statement-making We the People series. Launched immediately after his inauguration, the artist describes it as a response to the viler traits he saw in the then-president.

“Name any bad human characteristic and he has it — he’s almost like a caricature,” Fairey says, shaking his head. “I was proud of that series, but in its wake, I did more work about racism, xenophobia, sexism and environmental destruction to counter all the wrong things he was doing. Trump was highly motivating for me, but I also knew that he loved attention, so I didn’t make any art of him. He’s like a negative energy amoeba that just grows with hate, and I refused to feed that. His worst nightmare is to be ignored and be irrelevant. I’m just happy that we’re in a new administration, but there’s still a lot of poison in the bloodstream of the United States. The Biden administration has potential but constant vigilance is important, so we need to keep pushing them on policies that safeguard the most vulnerable people and the environment.”

Say it loud and clear

Subversion for subversion’s sake never interested Fairey; every endeavour needed a point, from calling attention to the commodifying of culture in favour of capitalism to rousing momentum for certain movements. Empowerment is a major theme, even in advertising work, where it can be a contradiction of trends.

“Some of our current advertising in the US has this almost slacker, who cares?, vibe to it. I don’t know if it’s snarky or kitschy; maybe it’s to make people who don’t feel smart or attractive enough think, ‘hey, that’s okay’, but I find that very defeatist, like it’s okay to accept that you’re a spectator in your own life. Sarcasm and irony can feel nihilistic. I tend to prefer sincerity or humour; it’s like the sugar that helps the medicine go down. It’s usually positive.”

The world has changed in myriad ways since André the Giant and his Posse was introduced but some fundamental truths remain. Human behaviour, for one. That, Fairey thinks, is how Obey remains relevant even after all these years.

“Many overarching concepts in my work will consistently appear because human psychology hasn’t evolved much,” he says. “I made my first anti-racism print in 1989. The good news is there’s been some progress in fields such as gender and racial equality, but it’s usually accompanied by an equal and opposite reaction from people who enjoy the status quo, like white supremacists. But I also think sometimes the most friction happens when there’s the most movement.

“To make sure that the core ideas in my work speak the language of the moment, I toggle back and forth between looking at big-picture ideas and patterns across history, and addressing current issues,” he continues. “Hopefully, my work has both timeliness and continued relevance. Some things find that balance better than others. I think I’m fairly fluent in speaking a democratic and inclusive language of symbols, imagery and texts that a lot of people can relate to. Not all of them can be icons like Obama or Obey, but it’s a constant process of observing and responding, rather than reacting.”

To reach the widest audience possible, he experiments with different approaches and partners a variety of organisations, allowing them to use or adapt his work, or even creating imagery especially for them to further a cause. A recent project, for instance, was a design for Seattle-based non-profit Amplifier’s global open call for artwork that promotes health and public safety as the world continues to battle Covid-19. In addition to being a jury member on the panel, Fairey contributed an image of a healthcare worker holding a torch à la the Statue of Liberty, with the words ‘Strength in service, strength to overcome’.

“I’m not a super social person,” Fairey admits. “If I’m on an airplane, I don’t talk to the person next to me. But I care about society and people. So, art is my social tool, it’s how I reach out to others. It’s also great personal therapy for me. The world’s problems deeply upset me and make me ashamed of us as a species. Art allows me to feel like I’m actually trying to do something to make a difference.”

Sometimes that means a political poster that takes a stand, and sometimes it is a mandala reverberating across a watch, reminding the wearer of the interconnectedness of all living beings. The medium — be it stickers, posters, clothing or timepieces — might be part of the message but regardless of canvas, every Fairey design is a striking statement of peace or hope.

This article first appeared on May 24, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.