Datuk Yong Yoon Li (middle, with plaque) and his family, alongside Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah of Selangor (third from left), accompanied by Tengku Permaisuri Norashikin (far right). Photo: Royal Selangor Malaysia)

As the fourth-generation custodian of Malaysia’s illustrious pewter dynasty, Datuk Yong Yoon Li has spent his life polishing traditions and forging new chapters for a family legacy that gleams across the world. Yet, even he could not have imagined his journey would one day grant him the improbable right to herd sheep across London Bridge toll-free, walk around town with a drawn sword or to drink himself merry without fear of arrest — all quaint privileges that come with being awarded the ancient and prestigious Freedom of the City of London.

“If you’re spotted drunk by the police, they’ll just put you in a car and send you home,” says the managing director of Royal Selangor with a laugh. “A freeman should be a person of good social standing — you’re not supposed to embarrass yourself or ruin the reputation of London.”

The title of freeman here — bestowed on those granted the Freedom of the City — was officially recorded as early as 1237. Originally a practical licence to trade, move freely within the city walls and avoid certain tolls, it survives today as an honorary distinction, conferred not only on Londoners but also distinguished individuals from around the world in recognition of their contributions to society. Over the centuries, it has been awarded to figures as varied and eminent as former British prime minister Winston Churchill, South African president Nelson Mandela, pioneering nurse and reformer Florence Nightingale and Queen Elizabeth II. This roll call of names also includes Malaysia’s Bapa Kemerdekaan Tunku Abdul Rahman, Selangor’s Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah, celebrity shoemaker Jimmy Choo, and now, Yong.

There are three ways to qualify for the status: by patrimony (inheriting it from a parent who was a freeman); nomination (sponsorship by two liverymen, aldermen or councillors); or redemption (application and payment of a fine). Yong chose the latter — the most pragmatic option — but pursued it through a livery company to establish a meaningful connection to his profession.

“I’m not getting any younger, and the traditional apprenticeship process is quite drawn out, so redemption was the sensible way. I wanted to do it properly, through a livery company, which entitles me to apply for the Freedom of the City,” he explains.

To formalise his ties to the discipline he has upheld for years, Yong sought admission to the Worshipful Company of Pewterers, one of London’s 111 livery companies founded over 550 years ago. “I’ve known many pewterers in the UK through my work,” he recalls. “At one point, a good friend of mine, Sam Williams from Birmingham’s AE Williams & Sons [the oldest family-run pewter maker in the world, established in 1779, and which has supplied the royal palaces with exquisite pieces from the original Tudor moulds] suggested I join the Pewterers. But you need both a proposer and a seconder. So we approached our common friend, Marc Meltonville, a royal food historian for over 25 years [who created period menus for Queen Anne dinner served in pewterware]. Marc kindly agreed to propose me, and my seconder was Laila Zollinger, a tin trader based in Switzerland.”

20250703_peo_datuk_yong_yoon_li_14_lyy.jpg

Yong’s path to joining the Pewterers began before Covid and stretched over 2½ years, a journey that included securing the Freedom of the City along the way. He notes, however, that he has yet to complete the traditional “clothing” ritual that would formally make him a full Liveryman.

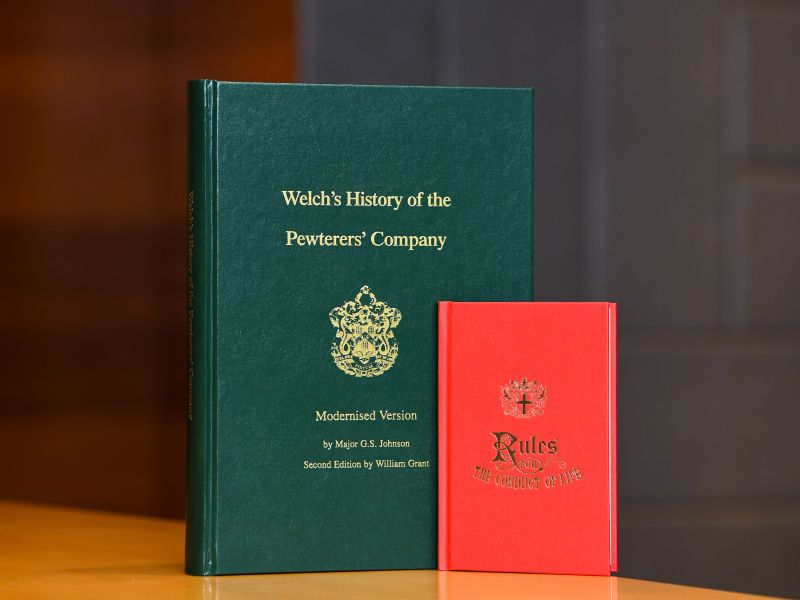

Yong’s Freedom of the City ceremony was held on June 20 in the Chamberlain’s Court at Guildhall. Before it began, the Beadle — the ceremonial officer of the Court — Jon Perkins, resplendent in a traditional frock coat, escorted the party into the room. After reading aloud the Declaration of a Freeman and signing the Declaration Book, Yong was presented with the Copy of the Freedom — a parchment document bearing his name, inscribed by a calligrapher — as well as a red book titled Rules for the Conduct of Life, which has accompanied new freemen since the mid-18th century. Based on a code of conduct drafted by Sir John Barnard, a former Lord Mayor around 1740, it offers guidance on business, behaviour and personal ethics. Though written in another era, its maxims — such as “Be in charity with all men; that is, fill your heart with a sincere love for all mankind, friends, strangers and even enemies, if you have any” — still resonate and remain applicable today.

“It’s a very small room, and even the Sultan of Selangor graciously attended,” Yong recalls with amusement. “You’re technically allowed to invite 30 people, but 34 showed up, including my family and friends. I felt a bit bad; [other recipients like] Charles Hay, the former British High Commissioner to Malaysia, only brought his wife; and lawyer Patricia Boon was accompanied by her parents and sister. Afterward, Tim Hailes [an Alderman — a senior member of the City of London Corporation, and also a pewterer] gave us a surprise tour of the Guildhall. He explained how it was damaged during the Blitz and showed us artefacts like a letter from Mandela and Nightingale’s casket. It was very interesting. When the ceremony concluded, I took all my friends over to the Pewterers’ Hall, just 20 yards away, for a casual reception and treated them to drinks.”

Beyond the celebration, Yong sees the accolade as more than a personal milestone — it also affirms Royal Selangor’s long-standing role as a cultural ambassador and symbol of diplomacy for the nation. “I think it adds credibility to what we do,” he reflects. “Within the circle of pewterers in the world, there are so few of us left. [The Freedom award] also reminds us of the importance of preserving skills, sharing knowledge and keeping the field alive, in both Malaysia and the UK.”

2_18_1.jpg

Through his ties with his British counterparts, Yong has embraced the spirit of camaraderie by exchanging ideas, finishes and even machinery know-how with peers at companies like AE Williams, finding ways to strengthen collective expertise rather than guarding secrets. “Whether it’s a new finish, new alloy or a new process, we share the information because the world is big enough for all of us. I’d send our R&D expert, Mr Ong, to check out, say, a machine that Sam recommended. When such time-honoured mastery thrives, hopefully, we can bring more young life into the scene.”

That sense of openness also extends to the business side. While acknowledging the challenges of the UK retail market — from skyrocketing utility costs to the loss of VAT (value added tax) refunds for tourists — Yong remains cautiously optimistic. “The outlook of 2025 is slightly better than last year. We’re slowly rebuilding,” he remarks, pointing to their flagship store at Battersea Power Station and steady wholesale relationships with retailers like John Lewis, Harrods and independent shops across the country.

Yong believes, however, that Royal Selangor’s mission goes beyond business metrics — carrying a civic duty to uphold and promote the heritage of pewtersmithing, not only at home but wherever its name travels. “We have people who’ve worked here for 40, 45 years, and others just three months. The question is how to pass that knowledge on and keep it relevant,” he reiterates.

That responsibility, he adds, also means defending authenticity in an age of digital shortcuts. “You can’t just get rid of your production engineer and hoodwink your customers by pressing play and — boom — everything’s done,” he says of the rising use of artificial intelligence in design and production. “It’s fine to use it as a reference, proof of concept or to streamline workflow. But the output itself still has to come from human hands. A machine can never replace that emotional connection.”

This article first appeared on July 14, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.