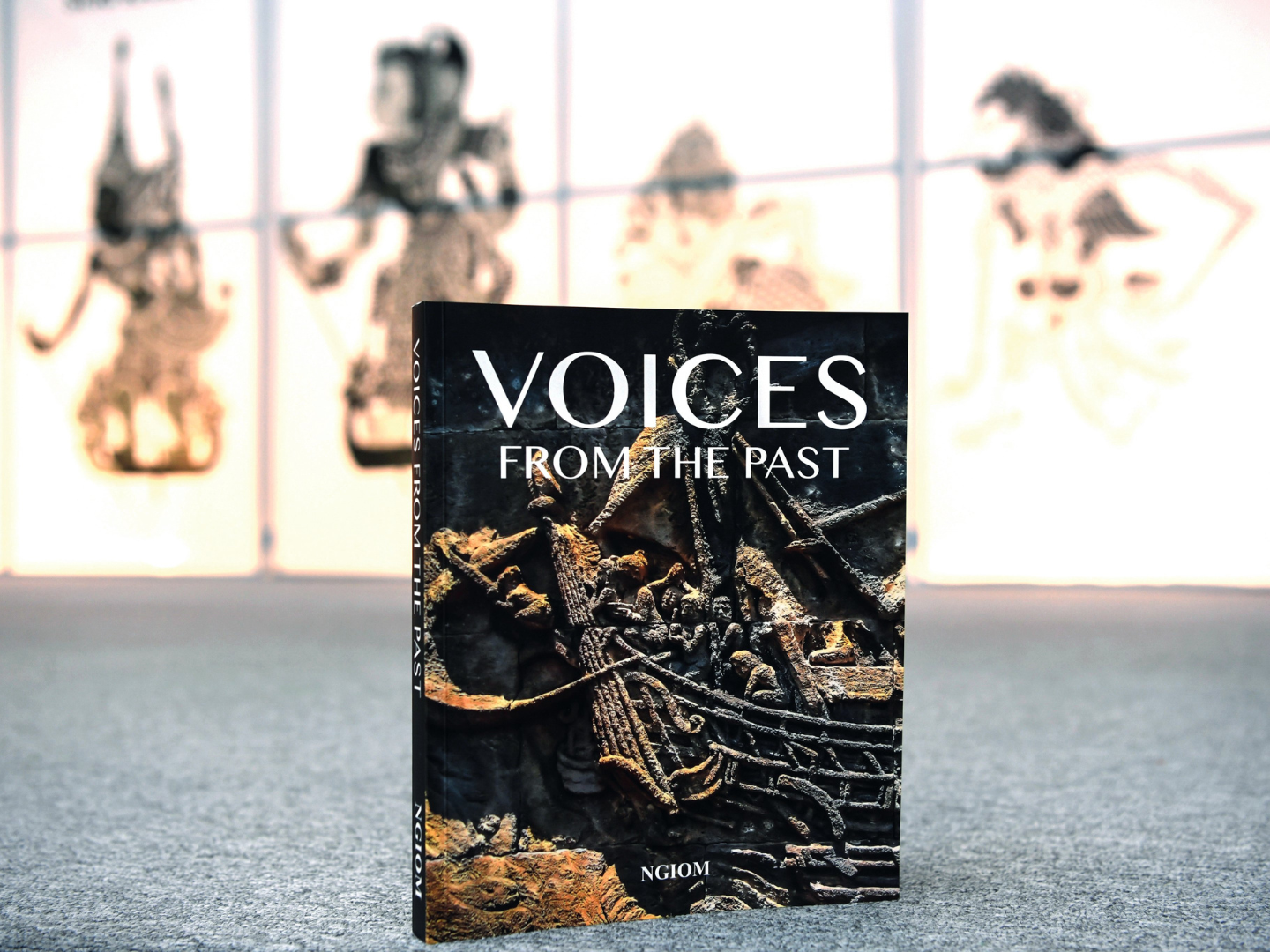

The book delves into the shared past of Southeast Asia's countries and the threads that bound its people together (Photo: Low Yen Yeing/The Edge)

Swipe, tap, scroll — these familiar motions and acquired habits have become practically second nature in the technological age. The online realm has also presented endless possibilities in how people perceive themselves, changing the way they comprehend reality and look inward.

Nowadays, it is possible to become anyone you want to be. Your identity can be fluid and multifaceted, crafted through a specific profile or persona that can vary depending on the platforms you use.

Yet, this freedom comes with some degree of unease. New ways of expressing oneself and connecting with others have raised issues about authenticity and fragmentation as the lines blur between the real and virtual.

As the world continues to morph with the use of technology and becomes further intertwined with digital media, what does it truly mean to be human?

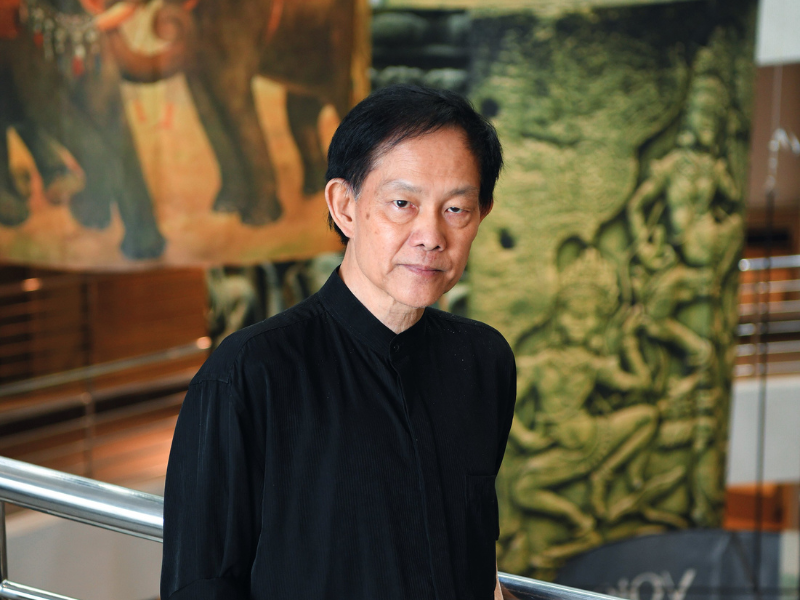

For architect Dr Lim Teng Ngiom, the answer lies not in chasing the future, but in looking firmly to the past. “Right now, there are conversations on mental dislocation caused by social media. What we need to do is dig deep to find the truth in our roots,” he says.

Having set up his architectural firm Ngiom Partnership in 1989, he has since gone on to design a wide variety of projects, including Amarin Wickham, a low-rise condominium in Kuala Lumpur inspired by the layers that make up the city.

Known for his experimental side, Lim also created the Countdown Clock in Dataran Merdeka, winning first place in an open competition held to commemorate the countdown to 2020. The monument is now part of the River of Life project.

1.png

His creativity, however, is not bound by buildings. He has always been drawn to stories of culture and history, while pursuing art through writing, sculpting and curating exhibitions and festivals.

This interdisciplinary approach underpins his latest publication, Voices from the Past, which explores the old tales of Southeast Asia and the shared threads that bind the communities together. “Our past is incredibly rich and interesting. Mostly, it anchors us, and gives us meaning,” says Lim.

The book traces developments across the region, drawing attention to interconnected communities that existed long before modern borders. “The thought process started some years ago when we visited Bujang Valley [in Kedah]. We found that it was actually a springboard for a massive civilisation that eventually reached its peak 1,200 years later,” he explains.

Drawing on his expertise in architecture, Lim delves into the magnificence of historical structures as well as the technology and lore behind their formation. Readers will find drawings and plans peppered across the pages, alongside visual depictions of what once was.

Significantly, recent discoveries of Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe in Türkiye, he notes, have stirred up previous theories and required historians to reconsider long-held assumptions. Similarly, Southeast Asia’s sites demand closer scrutiny. Voices from the Past examines landmarks such as Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, the apex of Khmer civilisation, as well as Indonesia’s Borobudur, the world’s largest Buddhist temple, and Prambanan, Southeast Asia’s second-largest Hindu temple after Angkor Wat. Bujang Valley, with the Merbok River forming its spine and Mount Jerai overlooking the coastline, is often described as the birthplace of Buddhist-Hindu culture in the region and plays a central role in Lim’s writing.

body_pics_3.png

Though the book is anchored by commentary on monuments and materials, Lim uses these as entry points to highlight other fragments of the bygone eras, intersecting migration, artistic lineages, ideological systems and intangible exchanges that shaped daily life.

Through the unearthing of stone remains and ruins, messages conveyed by the artistry of bas-reliefs are studied. He traces the movement of the Austronesian peoples — seafarers and landfarers whose descendants span Southeast Asia to Madagascar and Polynesia — and examines early empires such as Funan, Langkasuka and Champa. Religion prior to the spread of Islam and Christianity is explored through artefacts and inscriptions, revealing how belief systems evolved alongside industries like iron smelting, agriculture and maritime trade.

Much like how the West views Southeast Asia — with a sense of mysticism — other chapters cover more spiritual and mysterious legends, traditions and folklore. For instance, Lim looked at symbolic reigns and how certain buildings were constructed or engineered in alignment with the sun, cosmos or position of the earth. He noted that the buildings were built around rituals instead of usability.

The Sanskrit epic of the Ramayana was not left out — its narrative adapted across demographics and centuries. From wayang kulit to Thai and Malay interpretations, the classic tale of Rama has been repeatedly localised, demonstrating how shared myths evolve in different communities.

This continuity is echoed in classical dance traditions. Lim draws connections between apsara dancers — celestial beings rooted in Buddhist-Hindu mythology — and regional forms such as Mak Yong and Legong. Though performed in royal courts or folk settings, these dances share subtle gestures, fluid movements and symbolic hand positions, revealing a shared aesthetic language.

Even animals tell a story. Stone carvings depict elephants as instruments of war, ceremonial symbols and a mode of transport. Their recurring presence suggests not only practical importance, but also cultural reverence during what is referred to as the “lost centuries”.

Lim argues that these elements are seen to still hold influence in contemporary life. Although “the engineering marvel of Angkor City has not been surpassed to this day”, it can be seen that even the Petronas Twin Towers holds a resemblance to the religious monument’s lotus bud-shaped spires.

Another example can be drawn from the Austronesian groups, who were identified from shared words despite the vast geographical distances. In the modern age, Malay, Tagalog (the Philippines), Malagasy (Madagascar), Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Formosan (Taiwan) share a common vocabulary.

2.png

Supplementing the launch of the publication was an art exhibition held in December at the National Art Gallery. Simulation: Voices from the Past was designed by Octagon Design House and led by its creative director Melisa Wong Meng San, who believes in heritage preservation and modern innovation through design.

Upon entering the lobby, visitors were met with five gigantic lanterns suspended from the ceiling. Each floating ornament was printed with artwork based on Lim’s writing — images of apsara dancers dating back to the 8th to 11th centuries, wayang kulit puppets, seafarers and ships, the temple complexes and elephants in the midst of combat.

Vertical structures bearing stone inscriptions and Javanese manuscripts added a tactile dimension, while the main stage featured wayang kulit characters depicting Thai and Malay adaptations of the Ramayana.

“What we wanted to create here is actually an experience. The way it is done, there is a kind of resistance to the pervasive social media and the short narratives that go on,” says Lim.

In revisiting and amplifying ancient voices, this work poses a timely reminder that an identity is not only something to be solely curated online, but also something inherited, layered and shared. Perhaps, beneath the noise of the present, humanity has always found itself connected.

This article first appeared on Jan 12, 2026 in The Edge Malaysia.