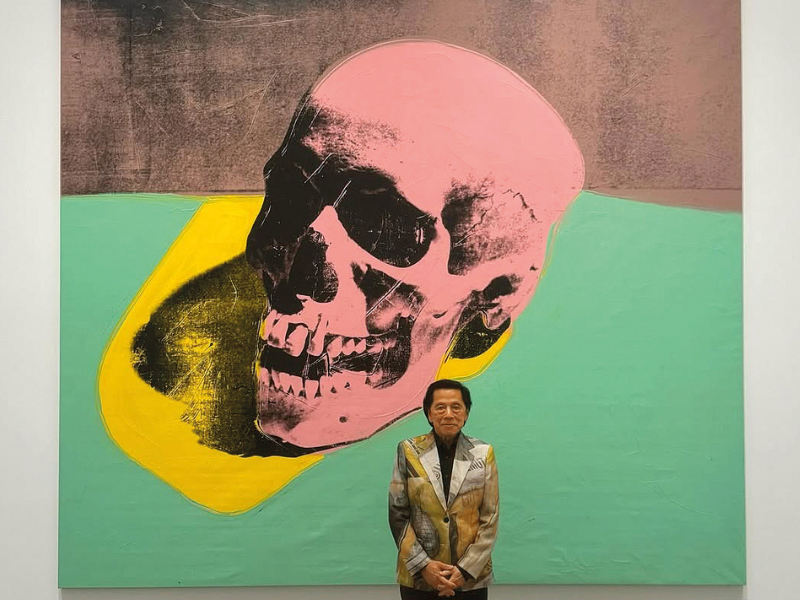

Jay at Uniqlo's 40th anniversary celebration at the Pavillon Vendôme in Paris, 2024 (Photo: Uniqlo)

One of the defining myths of America is its faith in optimism. Few examples capture this more vividly than the American Dream: the promise that those who begin with very little can, through determination alone, alter their fortune. Across generations, this belief in upward mobility has been distilled into a familiar tableau — a house with a trimmed lawn, a dream job straight out of college, or simply, the refusal to remain where history placed you. But for John C Jay, who spent his childhood in the back of a working laundry and did not live in a house of his own until the age of 15, aspiration took a far humbler shape. “One day,” he remembers thinking, “I will have a sofa.”

Jay’s family had immigrated to the US from Asia, carrying with them the pragmatism of first-generation survival. He did not begin learning English until he was six. Museums, exhibitions and galleries were mostly absent from his upbringing — not out of indifference but because they were never introduced, as his parents were focused on getting by. Like many children raised in immigrant households, Jay learnt early to temper imagination with caution: Art was permissible as a hobby, even a source of enjoyment, but making a living required something more dependable, safer. Creative impulses were tolerated insofar as they did not threaten stability. “You can do that,” his traditional father warned, “but you’re going to starve.”

As a child, seated amid the hum of washing machines, Jay would project himself 10 or 20 years ahead, pondering dimly whether there might be another corner of the world where he belonged. Education eventually provided the first real aperture. He enrolled at Ohio State University, just two miles from where he grew up, because leaving the city, let alone the country, was neither affordable nor conceivable. Once there, the fine arts major found his way — by luck, as he readily acknowledges — into design and visual communications, encountering European professors who taught the grid, a modernist system that imposed order through proportion and alignment, alongside Bauhaus principles and foreign magazines such as Domus. Each exposure loosened the boundaries of what seemed possible, revealing a vocabulary he had not known existed.

body_pics.png

Yet every so often, the future he envisioned brushed against the present. Walking across campus one afternoon, Jay noticed an envelope on the ground and picked it up. Inside were airline tickets to Paris, intended for a professor. Pilfering them felt unthinkable — he was still “an honest and dutiful Chinese son” — but he took the tickets home and held them against his chest, indulging the fantasy, through some kind of osmosis, of travelling to a faraway land. The episode also stirred an earlier memory. Years before, a family friend who graduated from nursing school had sent a postcard from the French capital, describing a fabled city where romance and history are written into its streets, pâtisseries perfumed with butter and sugar, and storied lanes layered with a mille-feuille of architecture. Jay studied the postmark with disbelief, as if it had arrived from somewhere impossibly distant: “It may as well have been Mars”.

That hunger for knowledge and the unknown found its outlet in print. Magazines became a means of discovering aesthetics otherwise inaccessible to him. Among them was GQ, then at its height as the definitive bible for modern men, blending fashion, photography, sharp reportage and hacks, from throwing back Sidecars in a natty suit to turning sideburns into a mane attraction. As a “naïve” college student, Jay persistently sent the publication letters, sometimes overly detailed critiques, weighing what worked and what could have been pushed further. It was, in part, a small act of rebellion; a release from what he felt was the constricting rigour of Swiss design pedagogy. Then, in his senior year, a reply arrived. An editor, struck by Jay’s editorial sensibility, invited him, without so much as an interview, to consider joining the desk in New York.

That exhilaration eclipsed even his impending graduation. He declined the offer, as he could not yet leave school, but the exchange lodged itself in his mind. If a student like him could elicit that kind of response, the constraints he had long taken for granted might be more permeable than he believed. Upon graduating, Jay moved to the Big Apple and began working in publishing, crafting covers and layouts for engineering and law journals. The subject matter was dense, technical and far removed from the cultural gloss that had first drawn him to the written word. But the work imposed a different discipline: It entailed problem-solving, critical thinking and visual acuity — values that continue to govern his vocation and, over time, have emboldened peers and successors to dismantle stereotypes about who can lead and be seen.

Tailored for tomorrow

5.png

Jay’s early professional life unfolded through detours and hairpin turns that, in hindsight, proved fundamental. A fortuitous connection through the son of retail impresario Marvin Traub led to a coveted position as Bloomingdale’s creative and marketing director. Before long, Ralph Lauren came knocking, but he passed on the opportunity, choosing instead to join advertising powerhouse Wieden + Kennedy in 1993 as global executive creative director, where he steered the agency’s expansion into Tokyo, Shanghai and New Delhi. Only days into the job, he was tasked with a mounting challenge: to revamp Nike’s brand presence. His inaugural — and most enduring — assignment for the sportswear giant City Attack (1994) scattered poster ads throughout the city, deliberately exposing them to rain, graffiti and time so the imagery would transform organically. As the visuals weathered and accumulated marks, they took on the character of public art, speaking with such immediacy they drowned out a season’s worth of declarative headlines. Jay spent 21 years at what was effectively an experimental lab, leaving a legacy later recognised when industry contemporaries named him among the most influential art directors of the past 50 years.

Success, inevitably, presents its own seductions — the conceit that experience confers certainty or that mastery travels intact across borders. Japan disabused him of this almost immediately. Moving to Fast Retailing, the parent company of Uniqlo, as president of global creative in 2014 and working within an environment honed by humility demanded a process of unlearning. Rather than exporting Western authority — or what Jay describes as the American tendency to “think you know it all”, a habit he calls a disease — the transition to Asia urged for renewed attention to listening. Sampling someone else’s ideas also means ceding space to those who inspire.

2.png

“I’m not an artist. You can call me a provocateur or a creative director. However, I think the latter is in serious danger. Oh my god, every marketing person is a creative director now. I’m sorry, but not everyone who starts a brand is one,” Jay asserts, with the conviction of someone who has watched the term lose its edge, having been acquainted with CEO Tadashi Yanai as early as 1999 on a campaign for Uniqlo’s fleece products.

“My role is to create the highest quality of experiences for the greatest number of people, tracing a line from everyday essentials to meaningful partnerships such as our newest ambassador Cate Blanchett. There’s also a need to respect the skills and talents of others, giving them a lot of ‘rope’ or freedom. But if the work isn’t good, you can’t just reject it — you have to actively suggest adjustments. I often ask, ‘Have I lifted my team higher each season? Have I helped them to be better? Do our stakeholders feel confident after engaging with my team? That’s what I have to do,” he says, nodding towards the designers beyond the glass door, hunched over screens and samples in his austere New York office on Gansevoort Street, surrounded by the grit and glam of Manhattan’s Meatpacking District.

If there is a criticism to be levelled at the current generation, it is not a shortage of output but a shrinking of curiosity. The problem, as he frames it, is engagement. Curators have a responsibility to move beyond skimming culture for recognisable symbols and instead to immerse themselves in it through art, music, literature and lived experiences. These give brands intellectual bite, not just relevance by association.

“If I take an Andy Warhol motif, plaster it across a product, and it sells really well, am I moving culture forward? Am I just layering references onto glorified merch or actually extending knowledge?”

For the cultural agitator, art is not an accessory to creativity but its justification. “It is one of the strongest reasons we exist. Human creativity is severely under threat. You can look up what’s trending — that part is easy. The harder question is: Why?” He recalls a moment that crystallised this frustration. A group of 50 research and development experts had flown in from Japan and spent their days confined to desks and meeting rooms only. “They were there for 10 hours daily. I couldn’t stand it. That felt wrong. That was stupid. You’re two blocks from one of the coolest magazine shops in New York, and minutes from seeing an incredible young Korean artist at the Whitney Museum. There’s no excuse to come all this way and not engage with what’s around you.”

3.png

That impulse ultimately informed the conception of Uniqlo’s LifeWear magazine. “It was never meant to be a pullout about clothes alone, and definitely not a round-up of recommendations you can lift from Time Out,” he explains. “The content is filtered through the tastes of the people who work here. Which record stores matter? Which barista makes the best coffee? Who’s quietly holding the vinyl scene together? Sadly, for all the talk of being avant-garde, there is no longer a Diana Vreeland, no equivalent to her Vogue or the original Harper’s Bazaar spreads she shaped. We now live in a publishing landscape determined by advertising departments, with the cult of celebrity standing in for real direction.”

The legendary fashion editor, whom Jay admired for her instinctive grasp of storytelling and uncanny ability to tap into the American zeitgeist, was someone he met at a gathering hosted by Diane von Fürstenberg in her Fifth Avenue apartment, overlooking the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The atmosphere in the living room felt almost theatrical: In the kitchen, the US Secretary of Defense was deep in conversation with a group of models about nuclear disarmament; over at the library, a 17-year-old hairdresser found himself engrossed in Greek history with a professor. Amused by the ease with which disparate voices united through dialogue, he would later replicate this concept — at Nike, among other places — on a more intimate scale of 10 to 12 people. A great deal can happen around a dinner table; Kinfolk, after all, began in much the same way.

“If you could invite the world to sit at a dinner table, who would it be? What’s of interest to you? You need to connect them.” Education does not reward those who observe from a distance, so organise your life around exposure, he seems to suggest.

Muse + musings

1.png

It does not take much to realise when a partnership sings or stalls. Managing that expectation and tension has become Jay’s second nature. Uniqlo launches around 20 art-driven projects annually, from its UT graphic T-shirts spotlighting both emerging and established artists to institutional tie-ups with the Louvre and MoMA. Behind these efforts lies a subtler hand, an aptitude for seeing uncertainty as opportunity, from which unlikely alliances have emerged. He has orchestrated kabuki theatre alongside Nigo, founder of streetwear brand A Bathing Ape; introduced Takashi Murakami to Billie Eilish; and, in a more unexpected move, helped facilitate a US$300 million endorsement deal with 20-time Grand Slam champion Roger Federer. Graffiti wizard KAWS, enlisted as artist in residence last September, is set to take on a more prominent role in 2026, deepening his involvement in curating the next roster of collaborators.

Perhaps, Jay’s persuasiveness and charisma stem largely from the fact that he inhabits culture rather than assembles it. Or it may emanate from the dramatic black-and-white uniform he favours, lending him an air of inevitability when advancing an agenda. What is unmistakable, however, is the fluency he brings to the room, flitting easily between referencing points, be it quoting the lyricism of folk icon Joni Mitchell or the aching prose of poet-author Ocean Vuong, whose oeuvre bears the long shadows of war, anguish and the disorienting absence left by his mother’s death.

Loss is also something Jay knows intimately. His son, Matt, died on Nov 22, 2022, from an undiagnosed heart condition. Six years earlier, the keen reader and learner had founded End of Summer, a cross-cultural art programme and artist residency that invites six emerging contemporary artists from Japan to live, study and create each August in the Pacific Northwest and Portland, Oregon. The initiative was entering its fifth year when Matt also curated the first exhibition in what was intended to be an ongoing series at the Tanabe Gallery, part of the renowned Portland Japanese Garden designed by architect Kengo Kuma.

“He was a visionary who lived his young life of 35 without compromise, caring deeply about equality. Guided by his own principles to build a better world, he always promoted fairness and justice,” Jay recalls.

Grief is usually uninvited, often sudden and always contained, like love with nowhere to go. But not every winter takes all and gives back naught — some alter the ground, preparing it for what comes next. For a bereaved father, unearthing the kindness that lived in his son and planting it in others became a way to heal.

4.png

“I’m always looking out for young artists on a very personal level. When I watch their thoughts and ideas bloom, it moves me more than anything I see at fairs like Basel or Frieze. I want to bring them to America — to experience art firsthand, live among other talents, and to create alongside those different from themselves. I want to place them within a hub of creativity unlike their own. Matt wanted us to be strong and to keep his work at End of Summer alive. Now, it is my responsibility to carry that legacy forward, and to allow what he began to continue evolving.”

This desire to give back echoes Jay’s longstanding view that creative expression — the simple, giddy pleasure of making — should not be the preserve of institutions alone but activated in service of the public. It is also the reason he established Art J Foundation, which supports global and home-grown practitioners via symposiums, guest lectures and financial aid.

“I was first influenced by Gutai, a Japanese avant-garde group formed in the 1950s that embraced radical approaches in the aftermath of war. They encouraged parents and their children to make art outdoors. That spirit directly inspired Uniqlo’s sponsorship of programmes today, which have brought families from all walks of life together to make art in the Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern. It’s one of many endeavours that makes the company distinct. Because in this rapid technological shift, one thing you cannot afford to lose is identity.”

He elaborates, “It’s easy to say, ‘Just be true to yourself’. But why do you exist, whether as an individual or a corporate entity? I say this all the time: No one wakes up in the morning thinking, ‘You know what this world needs? Another apparel brand’. No one. You have to articulate a real reason for people to trust and care about what you stand for. What problems are you willing to engage with in a landscape facing real and urgent crisis? It’s an attitude shift. The same goes for mindset. Some people don’t understand that the greatest investment you can make is effort — it’s literally money in the bank. When the young begin to equate working full-time with selling their soul, something has gone wrong. Those things are not the same. Staying in a bad company is selling your soul. Working for an a**hole is selling your soul.”

Taken together, Jay’s reflections point towards a larger inquiry into the narratives we construct around career, dignity and success. Perhaps the American Dream, as he encountered it during childhood, was never a fixed destination but a set of conditions: fragile, provisional and perpetually under construction.

“Many say it’s dead, or at least broken. But what worries me more is when they say it never existed. Work only has value when it’s grounded in purpose. Young people are smart; they are questioning inherited assumptions and preconceived notions — and they’re right to. There is a place for everyone but we, as their predecessors, have to build the platforms that give meaning first.”

A designer sofa now occupies Jay’s office. Once a modest wish, it now makes room, through generosity, for others to sit alongside him.

This article first appeared on Jan 12, 2026 in The Edge Malaysia.