Coliseum KL, one of the oldest cinemas in the country, was built in 1920 by the Chua family led by Chua Cheng Bok (Photo: Google Street View)

When I was a little girl, we often went to the Central cinema off Campbell Road (now Jalan Dang Wangi) to watch Hindi movies, especially reruns on weekend mornings — cheap matinees, as these were then called. Central was a modest cinema house, a single-storey longish hall of medium size with aluminium roofing and only ceiling fans at the time.

Memories play in the mind’s eye with amazing clarity, rather like the moving pictures. Walking into the manager’s office with Dad for “free list” tickets to which he was entitled as a civil service building inspector for the premises, and drinking ice-cold Green Spot as we waited. Then, to the candy bar for treats. Rustling through those long, black curtains, hands cold with excitement and anxiety to check whether the scheduled movie had started. Once inside the hall, seated on the bare pull-down chairs waiting for the countdown lead for the film to start rolling.

Alas, when it rained, hero Dilip Kumar’s romantic teasers had to compete with the pitter-patter on the aluminium roof to be heard. That was during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Standalone cinemas, some more plush than others, were the rule of the day — the Odeon, the Rex, the Coliseum, the Lido, then Pavilion, Cathay, Capitol and Federal. Movie-going was an outing for families, couples, gangs of friends and the odd solo film buff. The 1960s and 1970s were heyday decades for cinema the world over, a feverish age of movie-going. Then, the video cassette thing happened.

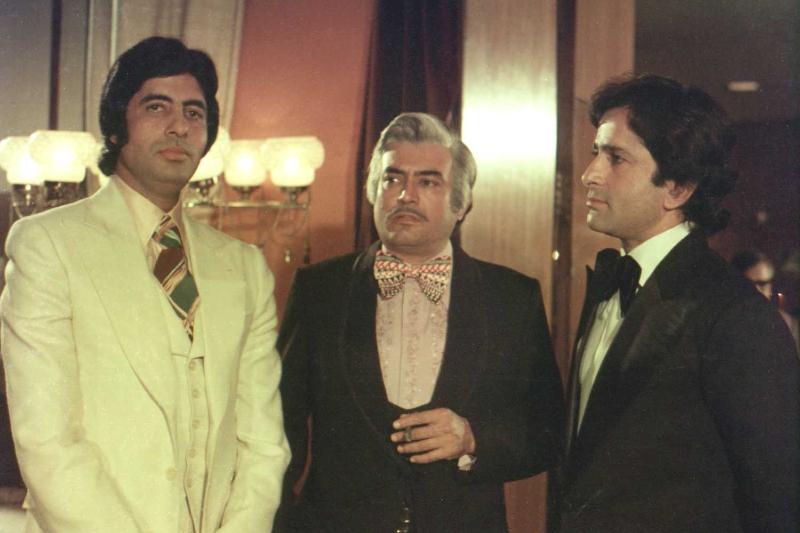

One rainy Saturday afternoon in the latter part of 1978, we were invited to a neighbour’s living room for a tea-time home screening of a new super hit Hindi movie, Yash Chopra’s Trishul (Trident). I was game, as I had been saturating my ears and emotions with songs from this new release. I was persuaded to make shortbread, and promptly at 2.30pm, we headed for the neighbour’s house — my mother, sister, the shortbread and me.

trishul.jpg

When all the invitees had arrived, the curtains were drawn and the show was on. The atmosphere in the room became progressively intimate and emotional as the thin plot thickened with one maternal sacrifice piled upon another and the theme of filial piety emerged. All mothers in the room simultaneously eulogised about the self-sacrificing nature of motherhood, comments punctuated with deep sighs and tongue-clicks, when hero Amitabh Bachchan suddenly grows up, a young man hardened by a rough tough life, and vows vengeance on the irresponsible father before the garlanded picture of his deceased outcast mother.

When the film ended, tea and all the tea-time goodies were brought forth. The steaming chai, made in good Punjabi tradition with fresh milk and cardamom, was just what we all needed then, what with the beating rain outside and our emotions spent inside. Content with the home video experience despite the home system’s imperfections and glitches, all the aunties did not venture to catch the movie on cinema screens.

The 1980s were a depression decade for cinema, with the advent of the VHS — video home system — phenomenon. People set up video rentals and even personal or communal video collections and, in homes, large looming TV sets became the desired norm. Video cassettes were developed in Japan during the early 1970s and affected the economies of the TV and movie business as the litter of videotapes became a ubiquitous part of the 1980s landscape, despite their bulky size, unattractive appearance and generic video-store covers. Next, the introduction of the DVD format during the mid-1990s replaced videotapes.

Film distributing and screening franchises then set about to change screening space formats, even as the video cassette moved on to the more digitally mastered DVD revolution, and a thriving pirate CD trade in art-house and banned titles and new releases continued to be massively successful operations.

Even as standalone cinema houses did not collapse overnight, in 1979, an 18-screen cineplex in Toronto’s Eaton Centre in Canada opened as a forerunner of a new trend in cinema screens. During the 1990s, the movie multiplex evolved to become the mainstay for cinema screenings worldwide, to cover multiple simultaneous screenings in a single venue, to cater for varied audience numbers and film preference according to genre and language, while also employing new technology to enhance the screen viewing experience.

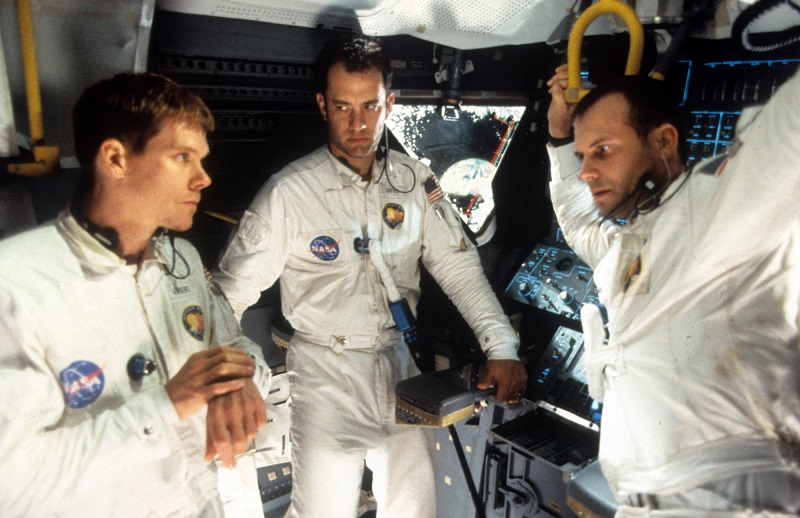

2apollo-13.jpg

In September 1995, the press was invited to preview Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 at Singapore’s brand-new Tiong Bahru Golden Village six-screen multiplex. The buzz of the cineplex foyer was a new experience then as we stepped off the escalator from the mall — bright candy colours, a whole wall of video screens muted on trailer previews, a computerised ticketing system, so efficient, yet intimidating, at the time. Armed with corn and Coke, we walked the star-patterned carpet to our “ergonomically designed seats with plenty of leg room for comfort, space and excellent sightlines”, to quote the sponsors.

Then the movie began, and I was once again swallowed up by the magic of the screen, this time also enveloped by a subtle sense surround digital sound system, the purring of the spacecraft simulating involvement with the space experience — involvement that is at the heart of the cinematic experience. Quite like children, we were enchanted under the spell of the screen. Later, a tour of the projection room showed that it was nothing like my memory of simple projection through a hole in the wall as seen in that Italian gem, Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso. Here was an upgraded centralised projection system that eliminated jump spaces between reels. Everything was pushbutton, reels were loaded for two to four movies at a time, everything on automatic mode. Thus the smooth continuity of my movie experience of Apollo 13, as I sat lost in the memory of an era during which I was growing up and man was trying to walk the moon. I forgot I was in Singapore.

Cinema technology was set to lure the crowds back to the movies despite further advances in laser disc recordings and piracy prices, poised to hand movie magic back to viewers in even more glorious splendour. Today, a pandemic-stricken world is forced to alter life as we know it. Like much else, studios’ shooting schedules and cinemas have been indefinitely put on hold — in some parts, certain establishments are tentatively attempting resuming and re-openings. But there is still a long road ahead, it appears.

heat_and_dust.jpg

People are at home working, cooking, cleaning and streaming. Streaming of information and entertainment content has become a major shift for producers and audiences alike. Music performances, drama series, lifestyle programmes, original content and now, increasingly, more feature film productions are primed for online release. During these times, when it is civic and wise to be confined, streaming is an absolute blessing, a new turn of events in the content and information industry that will no doubt affect the business of TV and cinema once again, but it is unlikely that streaming can replace cinema completely and forever. At worst, or at best, the two will become viable options in the long run.

What streaming is offering on the networks, especially in the docu-drama segment, is bold, realistic authentic content, though in many cases with excessive depiction of sex and violence in the absence of the patriarchal censorship outlook and practices in Asia. Streaming enables binge watching and the choice of timing and programmes, always with the option to switch off at will. The range of offerings is substantial, with more new productions on a weekly basis.

But there remains a certain other dimension of film and cinema, the nostalgia of a history that spans a century. American writer-critic Susan Sontag, reviewing 100 years of cinema, writes: “Cinema was an art unlike any other: quintessentially modern, distinctly accessible, poetic and mysterious and erotic and moral, and all at the same time … The strongest experience was simply to surrender, to be transported by what was on the screen … It’s not only the difference in dimensions: the superiority of the larger-than-you image in the theatre to the little image on the box at home. The conditions of paying attention in a domestic space are radically disrespectful of film … To be kidnapped, you have to be in a movie theatre, seated in the dark among strangers.”

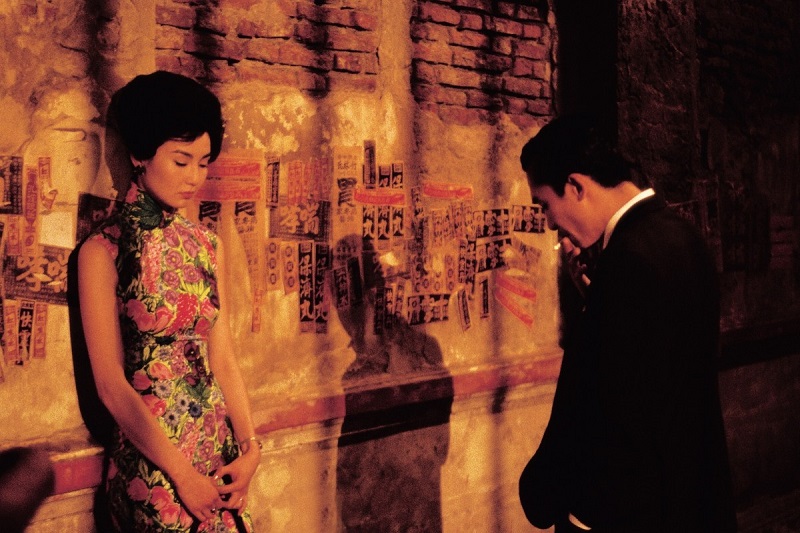

in_the_mood_for_love.jpg

Indeed. How could I have felt and fathomed the splendour and complexity of Merchant Ivory’s Heat and Dust in relation to the Subcontinent, to the extent that I did, had I not watched it in the gloriously aged Curzon Mayfair cinema in London. To be lost in the mise-en-scène of the haunting visuals of ordinary spaces; to feel the unsaid and yet get some intimation of the felt; the deep ethos of the music; the 1960s nostalgia in Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love — all of it may have been possible at the old dilapidated Rex cinema. To feel the lingering visuals of longing wistfulness and a wanton blue ocean; to register the docu-details of Mani Ratnam’s Bombay; to be enveloped and caressed by A R Rahman’s soulful music and lyrics — it may have to be Bombay’s original Art Deco cinema, Regal, at Colaba Causeway.

Cineplex cinemas the world over are convenient and comfortable. But I could never forget a movie experience at the Edwardian Electric cinema in Portobello, London, with champagne and perfect cucumber sandwiches; or the best coffee and a Judi Dench film at the Everyman in Hampstead? Then, there was Ramesh Sippy’s curry Western epic with action, comedy, tragedy, romance, song and dance, Sholay (Embers), which I watched at the Plaza in Connaught Place, Delhi, in September 1976 with the rest of India famously mouthing their favourite lines along with their film heroes. It was certainly my most immersive audience participation experience of India’s nationalist socialist cinema, complete with samosa and chai at intermission.

In Paris, sauntering down Champs-Élysées to watch a French slice-of-life film at a cinema hall, where smartly uniformed charming candy girls bearing a tray still come to your seat to offer their wares. In Sydney, cinemas in Paddington and Glebe were wonderfully different in outlook, décor and offerings — one artsy experimental and international; the other, Aussie kitsch. Here’s hoping such old cinema houses bearing the history of cinema in their walls are just on sleep sabbatical for now — we can wait.

Back in Kuala Lumpur, cinemas are now open, with limited screenings, sanitary and hygiene precautions in place, distanced seating, and age requirements. It may be refreshing to be lost in an imagined visceral time and space, displacing this malaise of 2020, for a couple of hours.

This article first appeared on Aug 31, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.