Injustice and corruption fuelled Ai Weiwei's desire to be the voice of the people (Photo: Violeta Santos Moura)

Translated by Allan H Barr, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows was written by Ai Weiwei to remember his father Ai Qing and as a remembrance for his son Ai Lao. The memoir opens with the author reflecting on his detention by the government of China, which then reminded him of his father’s experience as a political exile half a century before.

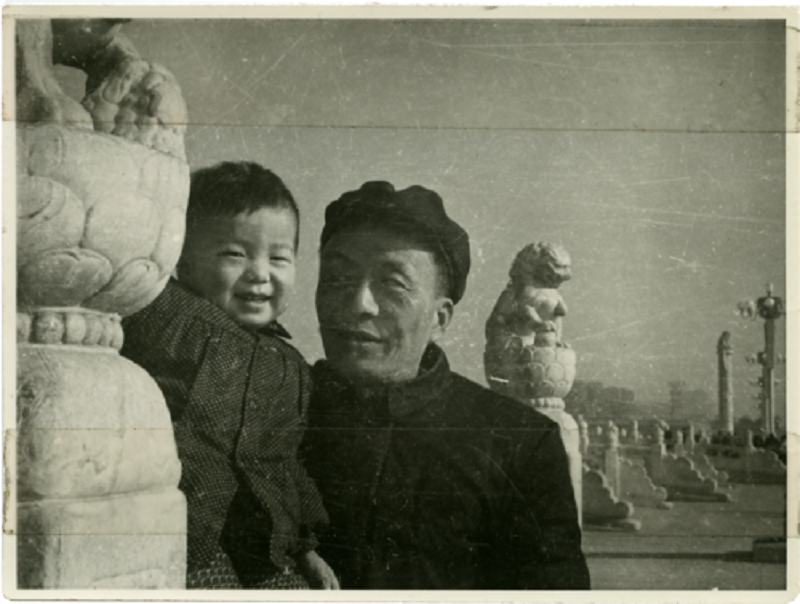

Ai Qing was born in a privileged family but raised by Big-Leaf Lotus, a peasant who drowned her newborn daughter in order to nurse Ai Qing to support her drunkard husband and their five children. Ai Qing was deemed “an ill omen” by his clan and would be “the death of his parents” if they were to raise him at home.

As a young child, the boy had shown profound talent and interest in arts: “Out of wood, he fashioned a miniature house with doors and windows that could be opened.” But this gave his father another reason to be discontented with his son as arts was accorded little respect in society at the time.

At 19, Ai Qing left Shanghai for Paris to pursue his passion in the arts. Being in a foreign country, his feelings of isolation deepened his desire for knowledge and he turned to literature to fill the void. Later, he would look back on his stay in France and conclude that it was the best time of his life as “never again would he experience such freedom and leisure”.

ai_weiwei_1000_years_of_joys_and_sorrows.jpg

As a prominent poet exposed to subversive things happening in the West, Ai Qing was viewed as a threat to the state and government of China; “he was now a young man, with an independent mind and the confidence to express himself”. A huge collection of books at his home often attracted the unwanted attentions of the authorities. With Ai Weiwei’s help, Ai Qing decided to burn down his whole library.

In his early twenties, Ai Qing was put behind bars for being a member of a revolutionary group, before being exiled years later during Mao’s Cultural Revolution to a deserted location called Little Siberia to undergo “thought remolding” after being labelled a purveyor of bourgeois literature and arts.

The family, including Ai Weiwei — who was 10 at the time — and his stepbrother Gao Jian, nested in a dugout that “took the form of a square hole dug into the ground, with a crude roof formed of tamarisk branches and rice stalks, sealed with several layers of grassy mud” for a decade.

Not able to withstand the hardships in his homeland after the release of his father, Ai Weiwei went to New York to pursue self-funded study. He studied arts and started participating in exhibitions before finding his way into photography. After being credited in The New York Times for a photo he took during a protest, he became interested in joining other movements and demonstrations, especially those fighting for freedom of expression.

1a.png

After 12 years, Ai Weiwei flew back to Beijing to spend time with his ill father. He found his native country had changed yet remained the same all at once. Many roads and tall buildings had been built, but the nation was still very harsh on the right to express one’s beliefs and opinions.

Injustice and corruption fuelled his desire to be the voice of the people, even if it meant walking the path his father had once forcefully taken: “I had changed, it seemed, from being an artist to being a social activist. It is not at all difficult to become a social activist: As soon as you start expressing concern about the nation’s future, you’re already on a path that could take you straight to jail.”

As a designer of the National Stadium for the Beijing Olympic Games, Ai Weiwei was condemned by architecture academicians who claimed he was trying to make China an experiment for Western architecture, owing to the heavy use of metals in the building’s structure. He had also organised a programme, bringing 1,001 Chinese on an overseas tour to Kassel, Germany, in an attempt to overcome the participants’ insecurity “instilled in them by political and cultural life in China”.

From then on, he began creating offensive art in the form of photographs, painting, writing, artefacts, architecture, films, documentaries and music to challenge the autocratic system. Obsessed with the deconstruction of classical order and ethics, Ai Weiwei’s provocative stance naturally antagonised the authorities.

New York was to Ai Weiwei what Paris was to Ai Qing. Similarly, blogging to Ai Weiwei was what writing poetry was to his father. It was not until the former actively started blogging and freely expressed his thoughts to thousands of subscribers that the authorities began to keep an eye on his every move. His blog became a public diary where he updated just about anything, including a picture of him being treated harshly by officers.

As an internationally renowned artist, Ai Weiwei was often invited to hold art exhibitions overseas. In 2011, before boarding a flight to Taipei, he was swarmed by police at the airport and taken into detention for 81 days, during which every movement and utterance required permission from the two guards in charge. Even after being discharged, the authorities never really gave Ai Weiwei a definite reason as to why he was taken away from society, as was his father.

The dreadful period made him look back to the person Ai Qing was and it struck him that he never truly knew his father’s story. Feeling like he could disappear forever at any moment during detention, Ai Weiwei decided to write this book so his son Ai Lao would have a trace of who his father was and the journey he had taken.

The 400-page 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows was not easy to finish in one sitting, as some of the events required you to put it down to process the author’s words, before picking up where you had left off. Hardship after hardship makes this book an intense read. With every chapter, it did not feel like the story got any easier. Given the nature of Ai Weiwei, who is extremely vocal and provocative, his memoir fairly reflected his journey.

This article first appeared on Jan 24, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.