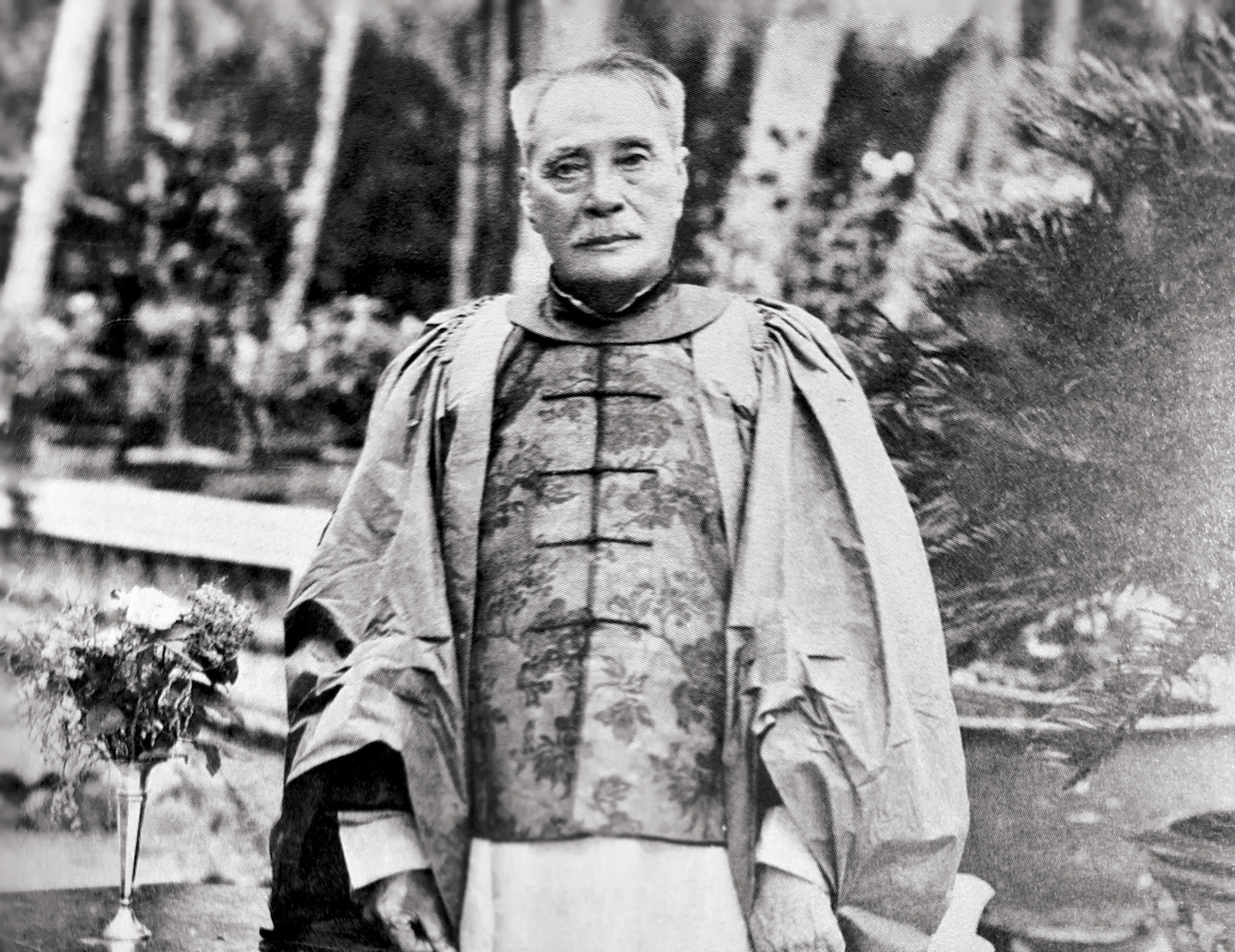

Loke Yew is representative of successful Asian entrepreneurial minorities within conjoint communities (All photos: Publisher Zamilyn Sdn Bhd)

“I began to have some idea how little the Chinese were protected in the last century and the early part of this, with a crumbling empire and civil wars at home and rejection outside: spilling out, trying to find a footing wherever they could, always foreign, insulated by language and culture, surviving only through blind energy.” (V S Naipaul, Beyond Belief)

Naipaul’s prose captures admirably only part of the story of Chinese migrants.

Loke Yew: A Malayan Pioneer by Neil Khor bears witness to one Chinese migrant who became successful in navigating the colonial rule and also the Malay polity. Loke Yew lived through the early 20th century amid the waning of British colonial rule. The Empire’s wealth from extractive industries like tin mining was built on the hard labour of coolies and their kapitans.

At one level, Loke Yew exploited the opportunities, including what the commissioning editor — his granddaughter Choo Meileen — in the foreword called “unsavoury” revenue farming. It is to the credit of this book that it does not avoid this aspect and hence this is no mere coffee table text and hagiography. Readers will find a clear chronicle and family trees accompanied by a rich trove of historical photos of personalities and places of Loke Yew’s life and times.

loke_yew_books.jpg

Loke Yew is representative of successful Asian entrepreneurial minorities within conjoint communities. In many ways, he exemplified the significance of “the stranger” who prized the growth of market societies with their concomitant drive for rational objective legal order, ably crossing the boundaries of ethnic identities and making a success of being a trader par excellence.

In the epilogue, the author articulates the challenge of writing a biography without actual written diaries or documents from Loke Yew’s own hand. Khor puts it vividly, “…this is a research process that resembles archaeology involving piecing together a personality from documentary evidence and whatever related to him from built heritage”.

From the Fujian province, Loke Yew was born around 1846 during a time of “great turbulence and warring factions in China, mostly attributed to the Taiping Rebellion and the Punti Wars” (conflict between the Hakkas and Cantonese).

The movement of being a Hokkien from a crumbling Qing dynasty to diasporic identity is an interesting theme in this biography. Over seven chapters, which read very well, Khor charts the progress of Loke Yew from the time he was a pioneer in Perak (1870-1885), through the middle years in Kuala Lumpur (1881-1900), the time when he was the most popular man in the Federated Malay States, his final years and his death and legacy.

Choo in her foreword outlined Loke Yew’s life in simple words, “His story is family folklore. Coming over to Singapore at the young age of fourteen or so, he worked … went north to tin rich state of Perak in Malaya ... He never gave up ...”

20200902_201039.jpg

This spirit of never giving up and yet conscious of his roots, grasping with adaptive intelligence for the opportunities that came his way, made Loke Yew not only one of the richest Chinese pioneers in Malaya but also one of the most generous benefactors in the fields of education and healthcare. The University of Hong Kong, rescued by a generous grant when facing imminent bankruptcy, and the current Tung Shin Hospital are concrete testimony of his benefaction.

His reluctance to bail out the collapsed Kwong Yik Bank in Singapore is instructive of his acumen. Instead, he promoted Kwong Yik in Malaya and extended its reach to semi-urban Chinese communities. This reviewer still remembers having a copy of Kwong Yik Bank’s constitution, which carried the names of Loke Wan Tho and Cheong Yoke Choy. Richard Holmes, the eminent biographer of the Romantics, states that a “biography is … a handshake across time, but also across cultures, across beliefs, across disciplines, across genders, and across ways of life”. To paraphrase Holmes, one wonders what else is in Khor’s notebooks, which “… open on both sides of the mysterious question. What was this human life really like, and what does it mean to us now?”

What does the narrative of this Malayan pioneer mean to Malaysians in the 21st century as we salute this book as “… not merely a mode of historical enquiry [but as] an act of imaginative faith”? Will Loke Yew be merely a relic of the past or will readers find in the book glimpses of the energy and spirit that animated and drove this entrepreneur to great heights and who adapted himself admirably to the community that he called his home?

This is a handsome text with excellent end notes, vintage photos and bibliography but strangely lacks an index. The proceeds of the sale of this book, this reviewer understands, goes to philanthropic causes.

Philip Koh is an advocate and solicitor of the High Court of Malaya.

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia on Sept 7, 2020.