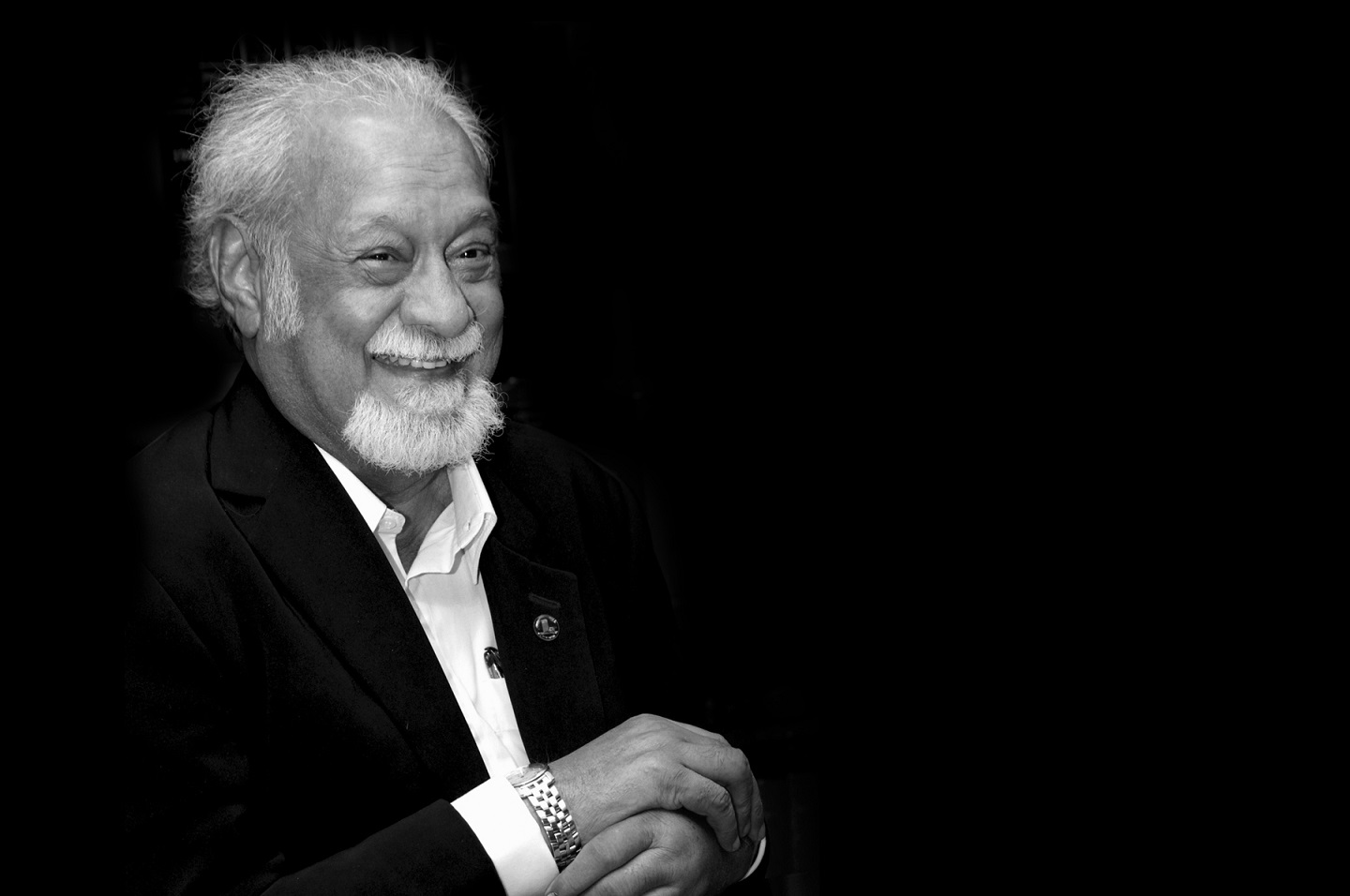

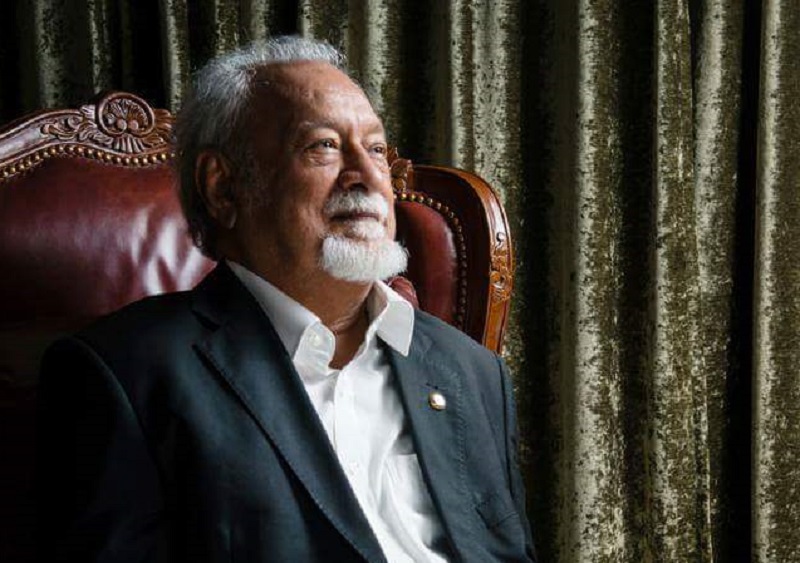

Karpal Singh, Malaysia’s most illustrious human rights lawyer and opposition leader (Photo: Rocketkini.com)

Karpal Singh: Tiger of Jelutong by Tim Donoghue is the biography of Malaysia’s most illustrious human rights lawyer and opposition leader. Nicknamed the Tiger of Jelutong due to his propensity to take on the most controversial cases and contesting political and judicial abuse, Karpal was equally famous for his tempestuous personality.

Karpal, who died in 2014 in a terrible accident on the North-South Expressway at the age of 74, dreamed of the day when the opposition alliance would form the ruling government. What would he have thought of the events of 2018 and the changing political face of Malaysia? He had worked tirelessly throughout his life, fighting for the end of capital punishment, civil liberties and a Malaysia for all Malaysians.

I decided to read the biography to understand more about the man who famously championed the principle of justice for all — that no one, not even political leaders and rulers, is above the law. He believed in safeguarding the principles of a secular state based on the Constitution and courageously spoke out against the implementation of hudud and laws that he perceived as draconian and unjust. Overtly outspoken, he was renowned for his cantankerous outbursts in parliamentary sessions and he earned a reputation as a troublemaker with his kicking up all kinds of “good trouble”.

Donoghue’s biography outlines Karpal’s early years and his extraordinary legal and political careers. He defended the rights of those facing the death sentence and fought the injustice of the colonial-era laws that were aimed at silencing the voice of opposition. Very quickly, he became the “unofficial lawyer” of choice for those facing the death penalty or for his political colleagues who were deemed to have contravened the Sedition Act and Internal Security Act. Donoghue goes through many of the landmark cases, such as the “School boy killers”, “Carpenter Teh” and those of international death row prisoners such as Kevin Barlow and Lorraine Cohen. He also covers Karpal’s own experience in detention. There are many enlightening moments in the book and Donoghue succeeds in validating Karpal’s actions and thoughts on various issues facing him and the country, both legally and politically.

Born to fight: The courageous Sikh

Karpal was born in 1940 in Penang to Ram Singh Deo, a watchman, and Kartar Kaur. His parents were first-generation immigrants from Punjab, India, who left their homeland in search of a better life. Ram realised that he had to leave his family farm to escape generations of poverty. Malaya was seen as the land of milk and honey, and Ram dreamed of obtaining a job with the police force as a bullock cart driver or a security guard. On his arrival in Penang, he was employed as a watchman and to supplement his income, he looked after a herd of cows.

Karpal’s family lived through the challenging times of World War Two and the brutality of the Japanese Occupation. Food was scarce and the family of 11 (six sons and three daughters) lived in a converted garage for many years. When Independence came, rather than leave the country with their white sahibs, they decided to place their family’s future with Tunku Abdul Rahman’s new government that pledged constitutional protection for all communities.

Karpal worked hard in school and went on to study law at Singapore’s National University. The pride of his family, which sacrificed immensely for his education, he took his time to graduate as he was passionately involved in the student union and politics. It was at university that he realised his calling — fighting for unjust causes. One such cause was the abolishing of the “certificate of political suitability” imposed on enrolling students. His journey of self-discovery in Singapore, where he found his voice, delayed the completion of his studies. This resulted in his taking eight years to complete his degree.

The Buddha and The Singh

Soon after starting his legal career, he chose to join the multiracial Democratic Action Party in 1970, a decision triggered by the May 13 racial riots. Four years later, he won his first parliamentary seat in Malay-dominated Kedah where he was working. By 1978, he decided to contest in his home state, Penang. His big win in Jelutong, with the largely Chinese entrepreneurial community, propelled his political career further. He kept his seat for over 20 years.

Karpal was well known for his clashes with Gerakan’s Lim Chong Eu. They were quickly labelled “The Singh” and “The Buddha” respectively. Quite often, the fracas would end with the police leading the agitated Karpal out of the state assembly. Karpal had even thrown his copy of the Standing Orders at the Speaker and was duly suspended from attending further sessions. The Chinese of Jelutong, however, loved their bearded Sikh fighter for rocking the political boat in the name of equality and justice.

Karpal stood firm in his belief that there could only be one law for all — everyone, whether poor or rich, should be treated equally. Very early in his political career, he locked horns with the then minister of works, Samy Vellu, bravely defended and challenged the royal families as well as Dr Mahathir Mohamad, the then prime minister. It is no wonder that he earned the name of Tiger of Jelutong.

Gurmit fights back

Donoghue’s chapter on Karpal’s detention in Kamunting with fellow DAP leaders as a result of Operation Lalang provides a historical summary as well as a behind-the-scenes description of the events, and the impact it had on his family, particular on his wife Gurmit, who had to keep the family unit and the legal practice intact. Despite the intensity of the situation, Karpal’s family, friends and political colleagues soldiered on with their quest to free Karpal and the other detainees, who included Lim Guan Eng and his father, Lim Kit Siang. As a result of his own incarceration, Karpal became an authority on habeas corpus.

His firm, Karpal Singh & Co, was badly hit by his absence. Gurmit took care of the business and family finances while acting as campaign manager for Karpal’s freedom. But the difficult days also saw kind assistance from many — the Chinese bankers who went easy on loan repayments, the legal community and even some of his death row clients in prison stood behind him. Fifteen months later, he was released and reunited with his family.

For the greater good

Donoghue writes that Karpal believed he had achieved more via the law than as a hardball opposition politician. Admittedly, he saw his greatest achievement in saving many clients from the gallows as his success. One of his proudest moments was when he saved a 14-year-old boy, charged with possession of a firearm, from the hangman’s noose. Together with DAP’s support, he managed to obtain a pardon for the boy. In the chapter called Execution is a gruesome tale of the experiences of prisoners just before their imminent death call. Karpal argued against the death penalty for fear of just one innocent person being put to death.

Karpal recognised that the use of the law helped him highlight the wrongs of his political opponents and save his political colleagues when they got into trouble. With the support of his life-long friend, Lim Kit Siang, he had become the watchdog of society. This drew much ire and criticism from his adversaries.

Despite the hardships that came his way — death threats, long-term detention and an unfortunate car accident that made him wheelchair bound — he soldiered on, serving his party as chairman. Karpal spent much of his final years representing Anwar Ibrahim at his own personal risk. Notwithstanding their differences, according to Donoghue, Karpal was largely motivated to fight for Anwar’s freedom to ensure he was free to be a legally electable candidate when the time came.

Contrary to what everyone thought, he did soften his position on DAP working together with PAS. The 2008 elections saw PKR bringing the two parties together and producing a DAP-led state government in Penang. However, his dream that Anwar Ibrahim would lead a new government by the 2013 elections did not materialise. His final hope was to secure an acquittal for his conviction for sedition before the 2018 elections. Sadly, he died a month after the conviction, leaving a void in Malaysia’s political landscape.

Would he have agreed to the opposition paving the way for Mahathir to lead the government in the 2018 general election? I think Karpal would have understood and seen the bigger picture, yet remain his sturdiest critic. In his later years, he had become more pragmatic. I imagine he would have felt comforted that his sacrifices for the country and his family had not been in vain.

Donoghue took over 20 years to complete this insightful book. An experienced international political and war-time journalist from New Zealand, he came to know Karpal after covering the drug trafficking case of Lorraine Cohen and her son, Aaron.

His all-embracing story on the life of Malaysia’s fearless opposition leader and human rights activist provides another side to the country’s political and legal history. The book also reveals the good, compassionate and brave man Karpal Singh was and his defence of the oppressed and marginalised. Love him or hate him, he was a man who could cause chaos out of the calm in any courtroom.

Nevertheless, democracies need men like Karpal to ensure the government of the day stays true to its responsibilities.

This article first appeared on Aug 27, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.