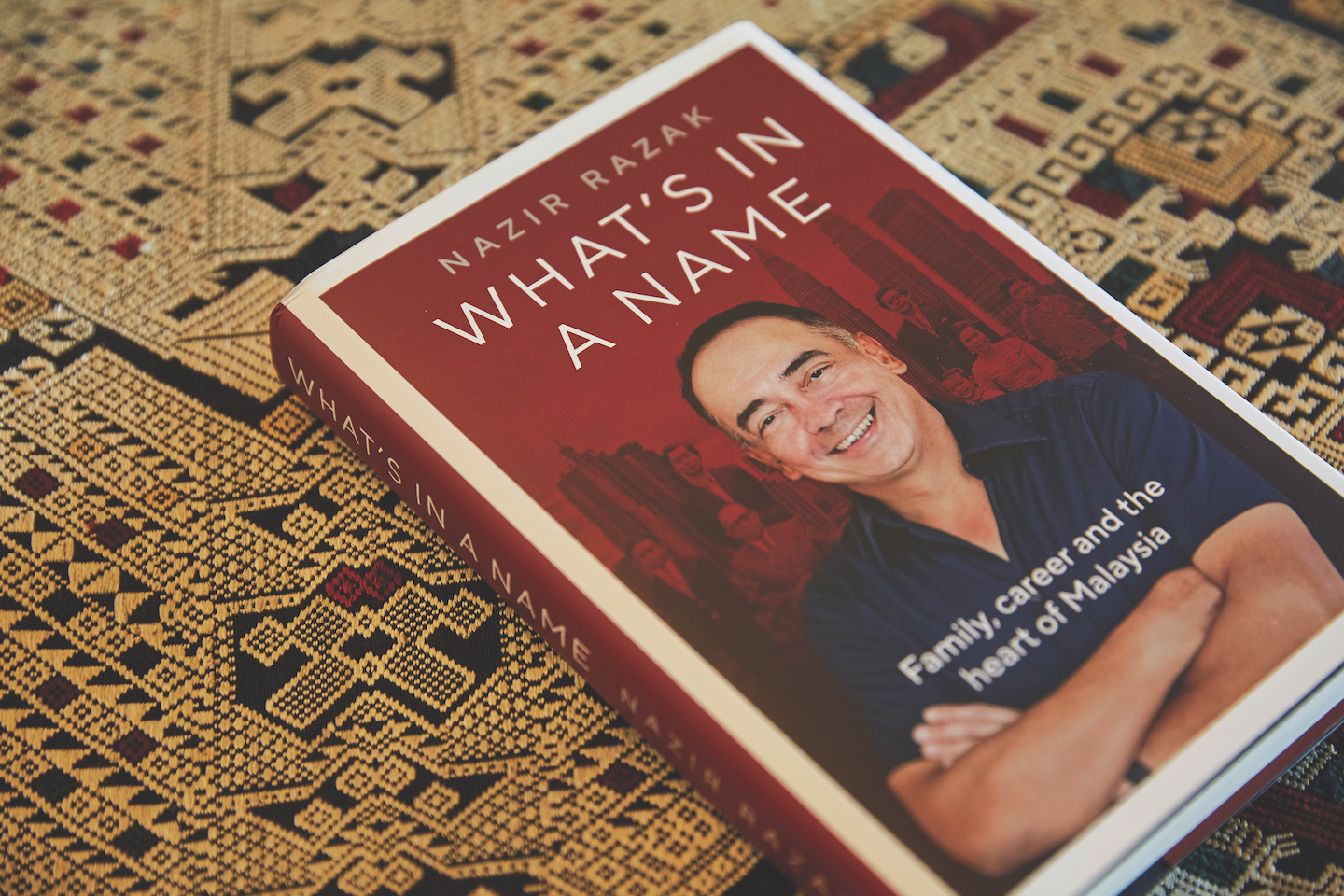

Many parts of the memoir were good reads about events and developments that as Malaysians, we can relate to (Photo: SooPhye)

What’s in a Name is a memoir by Datuk Seri Nazir Razak, son of Malaysia’s second prime minister Tun Abdul Razak and the architect behind the transformation of CIMB Bank into one of the largest banking groups in Southeast Asia.

What makes it a compelling read? Many people may know of Nazir as the banker who is synonymous with CIMB, the youngest brother of former prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak and son of Tun Razak. But how much of the persona that he presents to the public truly defines him?

This book provides an insight into a side of Nazir not always known to the wider public. His memoir, or reflections, as he likes to call it, chronicles three major periods in his life — his growing up years, banking career and the 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB) debacle — and the way forward.

The opening section of the book, Remembering My Father, takes us to the first nine formative years of his life at Seri Taman and a walk down memory lane to his father’s roots in Pahang. By all accounts, his childhood was a happy one, but certainly not normal by any yardstick, simply because of who his father was. Imagine watching from a vantage point of a balcony in his house the arrival of boxing legends Muhammad Ali and Joe Bugner for dinner, and Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in 1972.

“The prime spot was that gallery I mentioned earlier, at the front of the house, overlooking the entrance of the hall … from here, if you were small and insignificant, you could without being spotted, watch the comings and goings below of generals and ministers, civil servants and ambassadors and also from time to time, people even more glamorous.”

Perhaps more telling are Nazir’s reflections on his father, which he admits in Postface, a brief explanatory note at the end of the book, were largely drawn from stories told by family and friends, from books and photographs.

tr.jpg

No story on Tun Razak is ever complete without the mention of the May 13 riots, which sent the country into chaos after the ruling Alliance coalition looked set to lose the 1969 general election. A state of emergency was called, and power was handed over to the director of the National Operations Council, which was Tun Razak. It was also during these tumultuous times that Tun Razak took over the prime ministership from Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Tun Razak passed away in the UK when Nazir was just nine years old, with only his brother Najib around to share the grief. Soon after, Nazir was sent to a boarding school in Oundle in the UK, where he found himself to be the only Asian and had to learn quickly to fend for himself.

From his recollection, Nazir idolised his father, putting him on a pedestal as an example to follow in both his own career and personal life.

“I grew up the son of Tun Razak, the master builder of modern Malaysia, the structural engineer who put in place the foundations which have largely sustained the country till this day.”

From Nazir’s perspective, Tun Razak built a personal legacy over 25 years that defined much of the political, economic and social contours of the nation, even today. “That legacy has two sides, an obvious and more public side — made up of institutions, policies and programmes he enacted — and a less visible, more intangible and personal side, comprising values, principles and methods he applied, methods which I have drawn on heavily as I navigated the relationship between public and private, business and politics in my own career.”

In the second part of the book, Nazir talks about coming back to Malaysia after spending the whole of the 1980s in the UK, graduating from the University of Bristol and then doing a postgraduate degree at the University of Cambridge.

Nazir joined CIMB’s corporate finance team in 1989, when Malaysia’s capital market was on the cusp of taking off in a big way. Like any other of his teammates, he often worked late into the night, and there were times when he had to face the wrath of his boss, Steve Wong, whom he describes as a workaholic, hard-driving chartered accountant turned corporate financier. So, from the very start, being a Razak didn’t really win him any favours.

His stellar rise up the ranks at CIMB and how he led and transformed the banking group into a major regional play, as well as his metamorphosis from investment to universal banker are already well documented. But what is interesting are the untold stories, the actions behind the scenes, so to speak, that offer the reader glimpses into how Nazir tried to live up to the values learnt from his father. It was not always easy.

One such story happened in 2001, involving Tan Sri Halim Saad, Renong Bhd and Time Engineering. Renong was a major casualty of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis and was bailed out by its subsidiary United Engineers of Malaysia Bhd (UEM). In January 2001, Halim offered to buy a 21.5% block of shares in Time for RM875 million cash. He paid a deposit of RM2 million and owed another RM873 million. He had until July that year to raise the funds. But in June, Halim asked for an extension of the payment date. CIMB, as the merchant bank involved, had to make a decision. A failure to extend the payment date could lead to the collapse of Renong. Still, Nazir said no, and called Tan Sri Nor Mohamed Yakcop to tell him what he had done. “I said I wanted him to know that I did what I felt was right … but I fully accepted that there might be consequences. I thought I might be out on my ear. To my surprise, he replied, ‘Well done. You did the right thing. Come and help the government take over UEM and Renong from Halim’.”

Perhaps the toughest challenge in living up to the Razak name for Nazir was during the 1MDB scandal — doing the right thing conflicted with family loyalty.

When he first had an inkling that something fishy was going on at 1MDB, Nazir went to see Najib, who said he would look into it. That was not the only time he went to see his brother to press for the truth. He did his own investigations, took his doubts to the then 1MDB chairman Tan Sri Mohd Bakke Salleh and board member Tan Sri Azlan Zainol. To cut a long story short, Bakke and Azlan resigned from the board shortly after.

To put it in Nazir’s own words: “So, I stayed behind the scenes, nudging, prompting and encouraging our institutions and politicians into action. Had I done nothing, I wouldn’t have been able to look at myself in the mirror. Had I openly challenged my brother and split the family, I wouldn’t have been able to look my mum in the eye.”

There were repercussions. “My own family had been subject to a vicious and concerted attack online after I made veiled criticisms of my brother’s handling of the affair. Then to cap it all, my father’s good name was dragged into it, his reputation potentially tarnished in an effort to throw people off the scent. To not press for the truth to come out would now be tantamount to turning my back on my own father, the principles of public conduct that he upheld.”

Nazir also addresses the elephant in the room — the cheques he cashed for Najib in 2013, which emerged only in 2016 that they were drawn from the AmBank accounts into which money allegedly from 1MDB had been deposited.

In the book, Nazir explains that “the realisation that money from 1MDB had probably gone through my accounts was deeply distressing, and no doubt cast suspicions about my involvement in the whole saga”.

In response, he took leave as chairman of CIMB to allow an independent inquiry, which was carried out by lawyer Tan Sri Tommy Thomas and accounting firm Ernst & Young. Bank Negara Malaysia also conducted its own investigations. Nazir was subsequently cleared and reinstated as chairman.

He ends his book with a proposition — the setting up of NCC2, a proposal that grew from the first National Consultative Council established by his father in 1970. The NCC was the start of efforts to recalibrate the entire political, economic and social system of the country in the aftermath of the 1969 riots.

NCC, according to Nazir, paved the way for, among others, the New Economic Policy (NEP), a 20-year programme with the twin aim of eradicating poverty and eliminating the identification of race and economic function.

The NEP as we know it today did not succeed in achieving the results envisaged by Tun Razak. Nazir has never made a secret of the fact that the NEP today is a “distorted, twisted and often counterproductive version of the original creation”.

NCC2, he says, is needed to deliberate on a National Recalibration Plan. But he acknowledges: “The NCC2 cannot clear the way for a national recalibration unless it is confident of tackling the three-headed monster (role of identity, money politics and over-centralisation of power in government) and boldly reconfiguring and rebalancing our system.”

What do I like about the book? It is an easy read. It is informative. Given that I had to do a review, and the deadline was tight, I had to binge-read the book, which is almost 350 pages long, over three days. Many parts of the memoir were good reads about events and developments that as Malaysians, we can relate to.

The storyline is easy to follow, the dots cleverly joined. The reader is led almost effortlessly from one period of the author’s life to the next; from the early life of Nazir to his banking days and finally, to his frank essay on 1MDB, where he faced the toughest challenge of his life — family loyalty and doing what was right, the latter being a value handed down from his father that he repeated again and again throughout the book.

The NCC2 that he proposed may or may not succeed. Nazir is in the process of getting support from leaders from across the corporate, political and social spectrums to make NCC2 a reality. Setting it up is not the difficult part. Driving through the recommended reforms will be the biggest hurdle, given how entrenched the three-headed monster is.

Because he inherited a good name, Nazir has often been posed with this question: How much of your success today is because of who you are — a son of a prime minister and brother of another one?

Nazir’s memoir, at least for me, attempts to provide an answer. While he was born into privilege and a powerful family, his reflections on his career of almost three decades in banking portrays a man who has risen to the top with hard work, a far-sighted vision and agility.

“The name gave me advantages, for sure, but it also meant I had a lot to live up to, not least because I felt my father would be with me, urging me to be my better self.”

Anna Taing is managing editor at The Edge.

Purchase 'What's in a Name' at LitBooks for RM89.95 here.

This article first appeared on Nov 8, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.