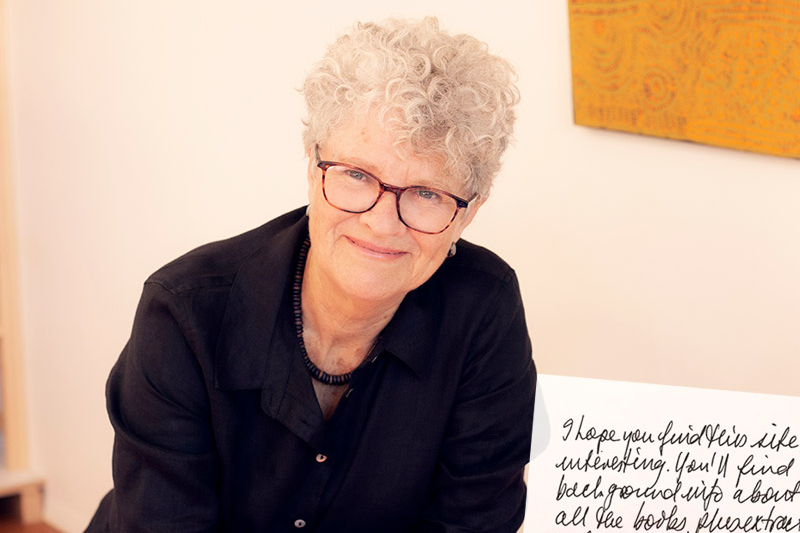

The author’s vivid captures of nature is impressive in 'A Room Made of Leaves' (Photo: Canon Gate)

Kate Grenville anchors fiction to fact in A Room Made of Leaves, dipping into documented accounts by early settlers in New South Wales to spin a novel that starts with this epigraph: Do not believe too quickly!

Just as quickly, the author has readers believing that Elizabeth Macarthur had left behind a secret memoir tucked under the roof of her home about her unhappy marriage to John Macarthur, the man credited with founding Australia’s wool industry. Years after he died — racked by lunacy towards the end — Elizabeth, in the evening of life, is free at last to speak and Grenville professes to transcribe her story.

Wariness had become a habit for Elizabeth Veale, a lass folded up small after her widowed mother rides off with a new husband, leaving her under the care of her grandfather, then the Kingdons in Devon, England. Wilful and clever but too curious for her own good, she falls for the flattery of John Macarthur, a poor soldier who woos her with hand on heart and a tilt of the head.

With child after a tremulous midsummer night and nowhere to hide, Elizabeth settles for marriage to moody Macarthur, a man lacking in looks, charm and means. The arrogant, ambitious son of a draper schemes to prove his worth. So, when the chance comes to set sail for the new penal colony of New South Wales in 1790, Macarthur grabs the posting and drags her along, seeing an opportunity to make money to pay off a debt.

kate-grenville-bg-v7.jpg

Through Grenville’s deft way with words, Elizabeth tells of adapting to Sydney Town, “a dusty ugly angry place, a sad blighted bit of ground on which too many souls trampled out their days dreaming of somewhere else”, living close to convicts, forming new social circles in the barren land, raising children and learning to read her husband’s moods and motives while keeping mum. He is blind to her as a person, but, with hopes of her own, she turns that to her advantage as he plots his rise from British officer to landowner, farmer and wealthy trader.

As the potential of an untamed territory where forest-dwelling natives pose threats to the new arrivals unfolds, Elizabeth puts down roots. Along the way, she grows too, from reserved, obedient spouse to a woman aware of her abilities and worth and finds her voice, however quiet. It is this voice that engages readers as days of drab greys and strange hard leaves turn into green patches dotted by sheep and fine wool and Elizabeth is reawakened by socially awkward resident astronomer William Dawes in a space enclosed on three sides by greenery.

This little room made of leaves is where they succumb to desire, not much different from what dogs and rams did, as innocent Elizabeth and Bridie Kingdon noticed everywhere after attaining puberty. It was also what the best friends gave themselves to between the covers because it was the most natural thing to do and gave them pleasure.

Grenville’s telling of Elizabeth’s story, following events and people named in letters, journals and official documents of pioneers who opened up Australia, leads readers from history to fiction, and truth to fallacy or falsehood. When they intersect — records show they do — her protagonist fills out and becomes more real as she digs her heels in and uses what grandpa had taught her about rams and ewes in Devon to cross-breed sheep and run the farm in the two periods lasting almost 12 years when Macarthur was summoned back to England to stand trial for grave misdeeds.

Against the big backdrop of a wild outpost that slowly becomes habitable, it is the mundane lives of the small people, convicts given a second chance for petty crimes — like Hannaford who stole a ram because it felt so right, or banished-for-theft Mrs Brown, who has a weightiness of spirit about her — that make lasting impressions.

The author’s vivid captures of nature impress too, and when Elizabeth finally realises she no longer dreams of sailing back to English pastures because “this land, this dirt and stones and trees” is home now, the reader feels her sense of belonging.

Short, well-paced chapters with succinct headers keep the narrative going. Elizabeth’s honesty — she admits to using her wiles and being as crafty as Macarthur when their plans dovetail — gives a raw edge to her thoughts on women putting on a public face and the choices available to them in the 1800s. Elizabeth grabs what she can, and dares, for a chance at fulfilment and happiness. The thrill of body finding body is brief but it reminds her she is still alive.

She misses no opportunity to emphasise Macarthur’s foul temper and ill intentions throughout her narrative — maybe more often than is necessary. But she remembers an instance when he was tender and sympathises with how, bereft of maternal love from childhood, he grew into a brute.

Natives fighting to hold on to what is originally theirs is part of the weave of A Room Made of Leaves, which continues Grenville’s focus on settler life in her historical trilogy, The Secret River (winner of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and a finalist for the 2006 Booker Prize), The Lieutenant and Sarah Thornhill. But that thread is tenuous in this novel — who is the aggressor, and who, the aggrieved? — and readers may not find themselves rooting for the rightful owners of the land.

'A Room Made of Leaves' is RM56 at Kinokuniya. Buy here.

This article first appeared on Mar 15, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.