The book consists of bilingual poems that emphasises hope for children born hidden and lost, and how they can grow with love, resilience and grace (Photo: Hartini Zainudin)

Datuk Hartini Zainudin could cry a bucket for all the times she scurried to pick up unwanted babies. But tears do not hold water for this long-time child rights activist, who admits to seeing things happen that make her feel defeated.

“When I started this work in 2005, people were flushing newborns down the toilet and throwing them in the rivers. I was picking them up every weekend, sometimes three times a week, because there were so many born out of wedlock and mothers didn’t know what to do. I would get phone calls, ‘This one sudah mati’.

“About 70% of the infants that were dumped died, 30% survived. People were selling babies in the hospital. As soon as traffickers knew a single mother was in with a baby, they would approach a third party and offer money, RM2,000, RM3,000. So, I’d go to the hospital with a second-hand car seat — because I don’t drive — and pick them up as fast as I could to make sure they weren’t sold,” says Tini, as she is known.

“If a mother could [not keep] or did not want her baby, I would take it and put it up for adoption. I would go through JKM (Jabatan Kesihatan Malaysia, the health department), make a police report, get welfare. I had a list of [potential] parents. There was no payment whatsoever.”

Baby-selling still happens but she chooses to focus on the happy stories of those saved. “I want to write something hopeful because there are options. I’m trying a positive approach to get people talking about foundlings. I want children to ask questions and parents to answer. We need conversations about abandoned babies because they are not safe.”

Thus The Foundling, her book of bilingual poems that emphasises hope for those born hidden and lost, and how, with love, resilience and grace, they can learn to face adversity and grow. “It’s about a lot of babies who get adopted, are loved and go to school.”

the_foundling.jpg

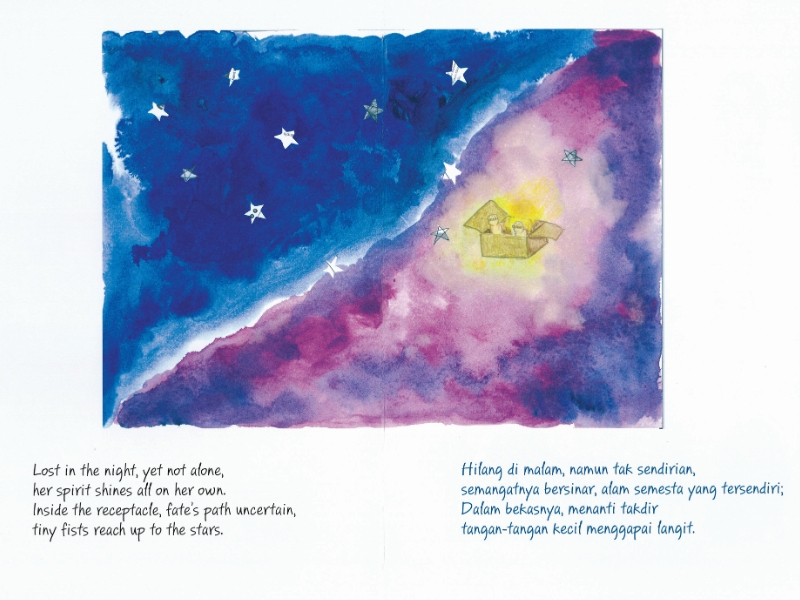

Malaysian visual artist and lawyer Ranerrim, who lives in London, captures the foundlings’ journey with colourful, uplifting illustrations that complement the text. Instead of dwelling on the dark side of fate’s uncertain path, they look to the stars for light to forge ahead.

Tini wraps up her literary effort with information on abandoned children or those whose parents are unknown. Poverty, stigma surrounding single parenthood and inadequate social support for struggling families are among factors that contribute to women leaving their babes behind.

With no birth certificates or other necessary documents, foundlings lack legal identity and may become stateless or invisible. Many encounter problems during the complicated process of obtaining citizenship. While they apply and wait, usually years, they are denied access to basic rights like education, healthcare and employment.

Part of the delay is due to uncertainty over whether found babies are born to Malaysians or foreigners, Tini says. “I can tell you refugees don’t dump their babies on the street or on top of washing machines in boxes. No. They give up their children only in the hospitals because they cannot afford to pay the high medical bills when they fall ill.”

Tini has been fighting for children’s rights, legal reforms and community support since returning to Malaysia in 2005 after 20 years of living in the US, where she did her doctorate in education at Columbia University, New York, and worked with underprivileged children and in refugee camps.

In 2007, she co-founded Yayasan Chow Kit (YCK) as a refuge where poor and marginalised children, primarily from that sub-district in Kuala Lumpur, can go to eat, sleep and take part in educational activities. A year later, she helped set up Voice of the Children, a non-governmental organisation that does advocacy work, policy reforms and training on children’s issues.

Tini is currently a fundraising and resource mobilisation consultant for both Give.Asia in Singapore and Anera.org. The latter reaches out to refugees and conflict victims. She still helps with cases at YCK and is pushing to introduce pilot projects on foster care for those who do not get adopted and have never had a proper family.

tini.jpg

The single mother who “fell into adoption” right after starting with YCK and has taken seven children under her wing, knows the importance of having a place one can call home.

“Now that my kids are going to university, you’d think I would be skinny. I’m not. I’m stressed, I eat cake, bite my fingernails …”

On the plus side, the blessings far outweigh the struggles, she says. “You don’t do this work because you expect anything. You do it because it’s what you believe in. You may not be able to eat blessings but you can live off them.”

At 63 and with eyes on the future, Tini has begun talking to Unicef about alternative family-based care for those who get kicked out of welfare homes once they turn 18. One suggestion is independent living, with some supervision and help for the rent until they can work and stand on their own feet.

She envisions a set of apartments in an urban setting or units by the beach, around which her brood can live, where they know someone is there and can go to if they are lost, like a compass or North Star, a beacon of hope and inspiration. Tucked inside one, she will teach, write books and cook for when her children come — to a home where they feel loved and wanted.

This article first appeared on June 2, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.