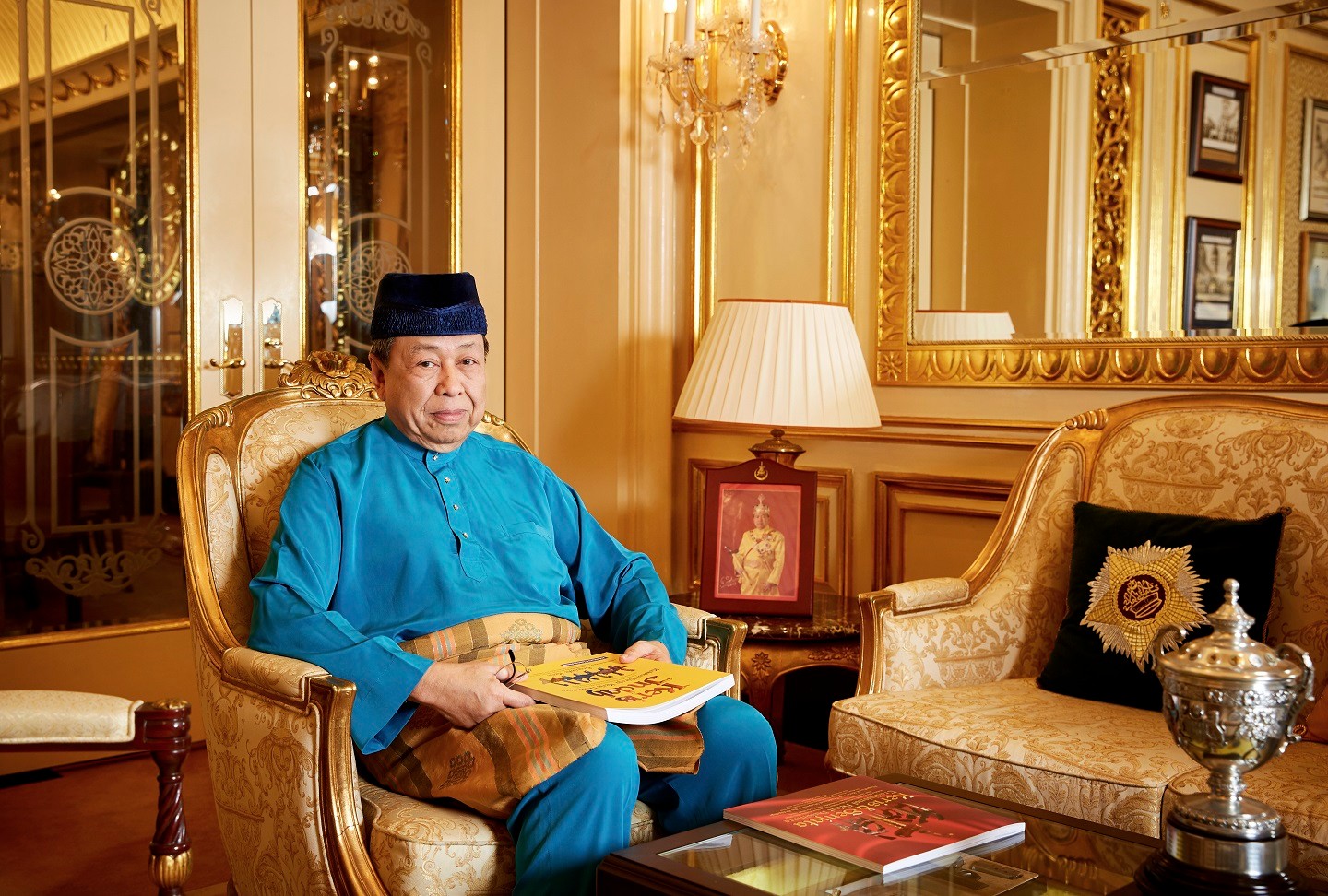

DYMM Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah of Selangor at Istana Alam Shah, Klang (Photo: SooPhye)

Malaysia might be a country that is still hurtling towards the bright lights of growth and development but part of its soul will always remain inextricably linked to the history and heritage of the ancient Nusantara region. Woven within its rich tapestry of people and culture is the motif of the keris, the traditional dagger that has long been considered a symbolic icon of the Malays. As Malaysian academician Prof Datin Paduka Setia Datuk Dr Aini Ideris aptly sums it up: The keris is “the cultural conduit” of the Malay world.

A WEAPON FOR WARRIORS

In the southern part of the royal town of Klang, just up the road from Jalan Istana and the 121-year-old Royal Klang Club, is the Istana Alam Shah, the Sultan of Selangor’s official palace. Used primarily for state functions, the sprawling palace is a treasure trove of royal artefacts, filled with all manner of beautiful as well as historic items that please both mind and eye.

On display are precious and historic memorabilia: woven songket from the Sultan of Brunei, a Cartier souvenir from the 1987 Berkeley Square Ball in London, a gold key from local jeweller Tomei and a pocket watch adorned with the Selangor crest by Garrard & Co. Framed photographs of dignitaries, including several of the British royal family — especially of the late Queen Elizabeth II, who visited and dined at the Istana Alam Shah on several occasions — adorn many tabletops and sideboards while display cases are filled with sumptuous gifts such as bejewelled jambiya daggers from the King of Saudi Arabia, alongside a medley of gadgets that pay tribute to the late Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah Al-Haj, father of the present ruler, who famously loved espionage-themed objects, as evinced by a spy camera and even a specially commissioned pen from Asprey of London that comes with an embedded pistol. “My dad loved gadgets, especially spy gadgets,” says Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah.

It is in the great hall of the palace’s Balairung Seri, however, that the air shifts from palatial grandeur to one thick with secrets and symbolism. Flanking the takhta (throne) are dozens of beautiful keris, which form just a small fraction of the sultan’s 1,000-strong collection. “Not many people know about keris,” he says. “It is still viewed with an aura of mysticism ... but I have collected keris for many, many years now. It is, I suppose, a legacy passed down from my ancestors.”

The royal family of Selangor are famously of solid Bugis stock, historical warriors acclaimed for being fierce defenders of peace and religion in the Malay archipelago. In fact, the first Sultan of Selangor was Raja Lumu, son of the famous warrior prince, Daeng Chelak, who later took on the title of Sultan Sallehuddin of Selangor in 1742. “We are Bugis. We are fighters! Many of my ancestors died fighting the Dutch,” says the Tuanku, in reference to the incessant battles that broke out between the two factions in the late 1700s and 1800s. “One of the most famous warriors was Raja Haji [Fisabilillah and younger brother of Raja Lumu, who led several raids on the famous Dutch fortress of A Famosa in Melaka]. You can visit his grave today in Indonesia, on one of the Riau islands near Singapore.”

ROYAL REGALIA

Although the keris surrounding the throne boast sheaths and stems primarily fashioned out of wood, they still conceal wavy forged iron blades that continue to inspire both awe and fear. Having been used in Malay culture and society for at least eight centuries now, since the days of the Malacca Sultanate, the keris remains revered and very much part of royal regalia.

When Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah was crowned the ninth Sultan of Selangor on March 8, 2003, at Istana Alam Shah, his coronation adhered to full royal customs and traditions, including entering the Balairung Seri behind the Lembing Sembuana, the 18th-century royal state spear made from steel collected from the state’s nine districts, and the long, straight Beruk Berayun keris. In official portraits, it is the Beruk Berayun keris, believed to be at least 300 years old, that can be clearly seen cradled in the ruler’s right hand while the resplendent Terapung Gabus keris, crafted from gold and studded with gemstones, may be seen to the left of his waist.

beruk_berayun.jpg

The sultan’s grandfather, Sultan Hishamuddin Alam Shah, had worn the exquisite keris as part of his ensemble when he attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The keris that symbolises the Selangor Sultan’s right to rule, however, is the Beruk Berayun. Only those with royal blood are permitted to hold it while the look of its blade — said to be coated with poison — remains a mystery to all except the Sultan, as it can be unsheathed only when the new ruler accepts the keris upon the passing of the old one. The Beruk Berayun’s intriguing name comes from a legend that the keris had once belonged to a mighty ape who used the dagger to kill 99 people many centuries ago.

CULTURAL COLLABORATION

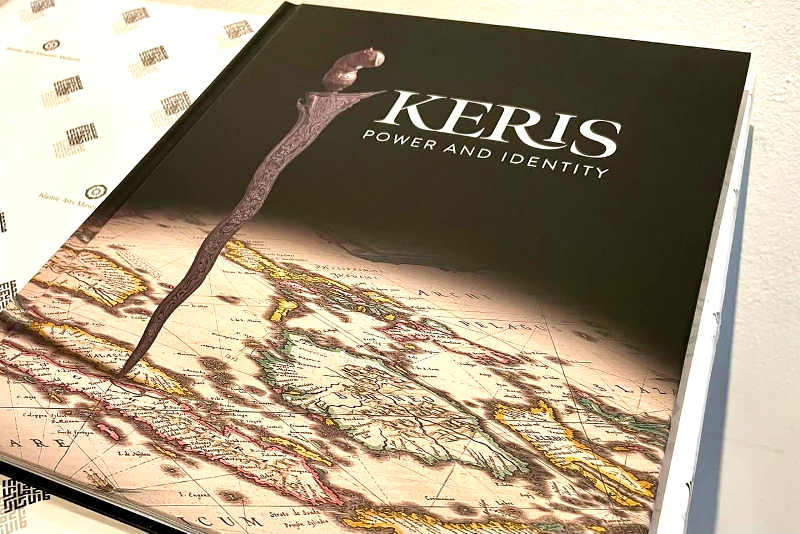

“You can see how the keris is very important for Selangor. And it was the Raja Muda of Selangor and royal patron of Yayasan Raja Muda Selangor (YRMS), DYTM Tengku Amir Shah, who came up with the idea of the exhibition,” says Sultan Sharafuddin, referring to the recently opened Keris: Power and Identity at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

In 2003, the Sultan, as its founding royal patron, envisioned YRMS to be a vehicle whereby the skills and talents of those who are not as academically inclined may be nurtured. The foundation’s programmes include cultivating creativity in sports or culinary and performing arts, skills-based training and life coaching and mentorship through self-discovery workshops. Assistance is open to all youths in the country between the ages of 18 and 29, regardless of race or religion.

On the founding of YRMS, the Sultan shares how he got the idea when he was still Raja Muda. “I was so impressed by the work The Prince’s Trust was doing,” he says, referencing King Charles III’s initiative to improve the lives of disadvantaged youths in the UK when he was Prince of Wales. “I want young people to find their strengths, find purpose ... and for the Yayasan to be a source of support so that everyone can earn a halal living.”

_s1a8409.jpg

It was five years ago that the Yayasan embarked on a new and exciting creative programme revolving around the keris, when it discovered that there were fewer than 10 surviving artisans in the whole of Malaysia. “We realised keris-making was a dying art. We could not even find any apprentices in Selangor,” says Raja Tan Sri Datuk Seri Arshad Raja Tun Uda, chairman of YRMS.

It was this desire to preserve an ancient art form so integral to Malay culture and identity that YRMS selected and sponsored three outstanding young men to undergo training with five renowned keris artisans from Pahang and Terengganu under its debut Talent For The World: Young Keris Makers project. The trio — Muzaffar Mohd Zafri, Ahmad Azuan Othman and Abdul Halim Zulkifli — worked with five masters, each specialising in different aspects of keris-making, from forging blades to hulu (hilt) engraving. “Their training began in 2019 and was completed this year. It was meant to finish a little earlier but the lockdowns bought us extra time,” says Datuk Syed Haizam Jamalullail, a member of YRMS’s board of trustees. Together, the protégés will present their finished works of art — Five Lok Bugis Keris with Snake Pamor, 21 Alang Keris with Sari Bulan Sampir and Bugis Blade Keris with Peacock Feather Pamor — as part of the royal exhibition.

THE ROYAL COLLECTION

Keris: Power and Identity, which also marks the inaugural collaboration between YRMS and the Islamic Arts Museum, is divided into six key sections: the keris’ Realm and History, its Art, Shared Heritage, Symbol of Sovereignty, Faith and Continuity of the Legacy. What makes it extra special is the display of 94 important keris, 59 of which are graciously on loan from Sultan Sharafuddin’s personal collection.

keris_iamm.jpg

“I have been collecting keris since the 1970s,” he says. Besides keris, the ruler is also a keen collector of first-edition Malay books and embodies the innate Bugis skill of exploration and seafaring, creating history in 1995 by being the first Malay royal to successfully circumnavigate the world in his yacht Jugra, covering 27,940 nautical miles in 21 months, as well as driving an antique 1932 Ford Model B car (cutely nicknamed “Humpty Dumpty”) over a distance of 16,000km in an epic road trip that criss-crossed countries and continents, taking him across China, Tibet, India, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey before journeying through most of Europe and finally finishing in France.

Sultan Sharafuddin says: “I agreed to the exhibition, as the keris is important and part of our history, our identity. Many Malays themselves do not know the stories or the meaning behind the keris and its elements. For example, did you know that the general rule for the length of a keris’ blade is supposed to be the circumference of one’s head?”

The Sultan also shares how he has to clean the blades himself. “Preferably once a week, if I can, and usually in the evening, after Maghrib prayers. Many don’t know that the keris also has to mandi (bathe),” he laughs. Adding to the dagger’s mysterious aura is the fact that the Sultan himself — and no one else — has to clean it by letting it come in contact with his skin. “I use very fine sandpaper or air limau (lime juice) first to remove the rust and then a type of non-alcoholic perfume, which the Arabs love and which I buy from Saudi Arabia whenever I can, to clean the blade using my thumb. Most of the keris are still very, very sharp so you have to be careful. Some keris used to be coated with poison ... possibly made from the sap of the Ipoh tree, I was told.”

LEARN + SHARE

Although the Beruk Berayun and Terapung Gabus keris are too precious to be loaned out, visitors to the museum will nonetheless be treated to a visual and mental feast. The keris in the Sultan of Selangor’s collection come from all corners of the Malay world, from throughout the peninsula to Kalimantan, Sumatra in the west, the islands of Java, Bali and Lombok and all the way northeast to Sundang. Each piece is unique and precious, of course, but there are undoubtedly special ones to pore over, particularly the Keris Selit Diraja, made from full ivory and 24-carat gold embellishments for the hilt, scabbard and ganjar (cross piece) part of the blade, and the Keris Bugis Sumbawa, believed to have once belonged to president Soekarno of Indonesia. The latter is a particularly marvellous Sumbawan example of a keris with strong Bugis design notes that include the patah tiga hilt and boat-shaped sampir (top sheath). This keris is also unique due to the curved stem of its warangka (scabbard), carved from deer antler and decorated with a mix of floral, geometric and scale patterns.

keris.jpg

Aesthetes should also look out for the Bugis Terengganu Lok 9 (Nine Wave Terengganu Bugis) keris, whose blade pattern, or pamor, features a shower of gold design at its base and petai seeds in the middle; the Melela keris with its Bugis chieftain-style top sheath and pendokok (hilt cup) fashioned out of gold-plated silver with peluput leaf and fish roe motifs; and the Sumatran Gold Dragon keris, whose bilah (blade) features a royal dragon riding along the length of its 11 lok (waves) while the silver batang serunai (stem) is exquisitely adorned with floral motifs.

Stressing the urgent need to preserve and document keris’ vital role in the region’s history and socio-cultural fabric, Sultan Sharafuddin shares how some of the finest collections of rencong, an Acehnese weapon that plays equally important ceremonial and military roles in local life, were lost when Sumatra and its surrounding areas were devastated by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. It is with this in mind that a special 228-page book commemorating the exhibition has also been published and made available for sale at the museum shop while educational talks and demonstration workshops are regularly scheduled until March 2023 in a bid to share this distinctive treasure of the region with the world.

“We should and must preserve our history and traditions,” stresses the Sultan. “In the olden days, a father would always present each son with a keris, which they then treasure as family heirlooms. My son hasn’t started collecting keris yet, but he knows what it’s about. I gifted him a beautiful one, studded with jade and, funnily enough, its blade is getting darker. Keris is more than part of just a rite of passage ... It is part of the Malay baju.

book.jpg

“Just like how these young keris-makers have found their mentors, I want the YRMS to continue inspiring young people to find their calling. Schools need to teach culture more. I have always believed in the power of education. If you don’t understand something, you are blind and then make statements that easily hurt others,” says the Sultan cryptically. “After all, we are one big family ... We are all Malaysians. We need to remind each other to work together, to be harmonious. We should not be conscious of race, boundaries, geography or barriers. There is only one time when I am conscious about these things,” cautions the ruler, albeit with a twinkle in his eye. “And that’s when it comes to football! Then it is only Selangor, Selangor, Selangor [FC] all the way!”

The Keris: Power and Identity royal exhibition runs until March 13, 2023, at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia while the 228-page book is on sale at RM145 at the IAMM Museum Shop. For more information about the activities, talks and workshops, see here.

This article first appeared on Dec 12, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.