The late Ibrahim Hussein (fondly referred to as 'Ib') is famed for his evocative artworks

The arc of poetry and painting: the poet’s lurch towards the painted.

In an attempt to cultivate his powers of precision and detail, the young German poet Rainer Maria Rilke apprentices himself to the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Exhorted by the grand artist to “set his eye on pure subject”, Rilke ventures to the Ménagerie of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris to settle on the caged animals from which is born his stark poem Der Panther: Im Jardin des Plantes, Paris (The Panther: In the Jardin des Plantes, Paris).

During the fiercest periods of the National Revolution, Chairil Anwar, the “wild beast” of modern Indonesian poetry and of the broader Malay Archipelago, becomes besotted by the radical visions and revolutionary fervour of the painter Affandi.

“If I were to be done with words,” he would write in a dedicatory poem To The Artist Affandi, “lack the courage to step into my own home … my hands crippled, writing dead, dreaded suffering, dreaded dreams, then give me a place in the high tower, where you yourself stand tall …”

In an obligatory gesture, Affandi would forge a series of paintings depicting the tortured poet, increasingly red-eyed, always emerging from a storm of strokes that reflect a tempest, or a furnace.

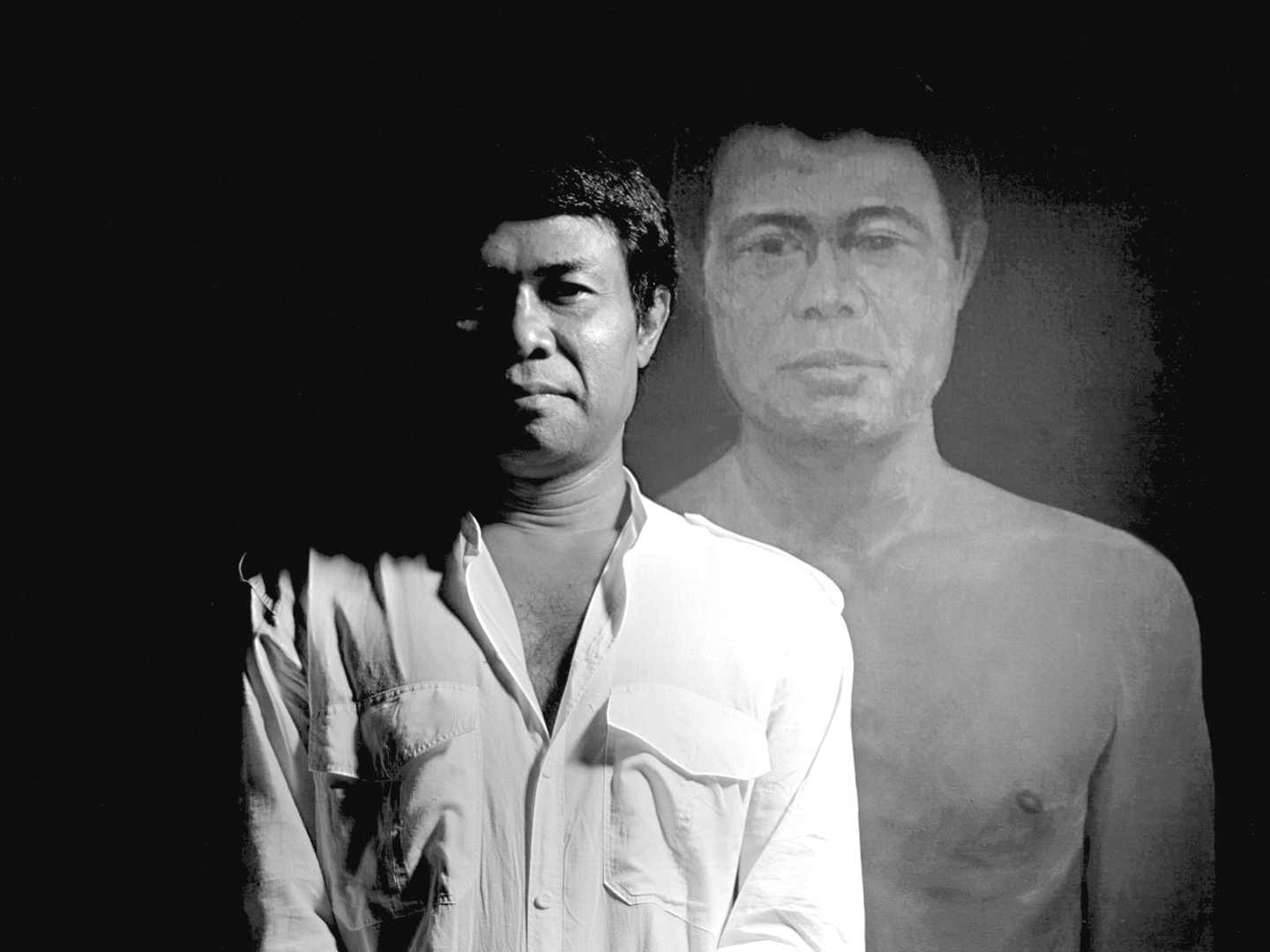

In his own tribute to the “wild beast” of this region’s artistic spirit, Ibrahim Hussein (fondly referred to as ‘Ib’) would offer one of his most evocative paintings, simply entitled Chairil Anwar, that reflected his most sustained preoccupation — the perennial tension between the world of the interior and the world beyond.

In Ib’s work, the poet emerges from a background of earthened volcanic red, the duality of Chairil — the sensitive and the sneering — two heads drawn from a single composite body, gauzed in a cloud of white and ash, with the eyes, described by the formative Indonesian writer Mochtar Lubis as “… aflame. Chairil Anwar in flames.”

The portentous year of 1969 would prove a watershed for the “boy from Sungai Limau Dalam, Kedah” who was by now the worldly Ibrahim Hussein. Life as an art student in London in the heady days of the 1960s would eventually pave the way for Rockefeller and Fulbright fellowships that would take him through many parts of the US and eventually a celebrated exhibition at the Newsweek Gallery in New York. Along with the experience of an America in tumult came greater experimentation not only with subject but also material and technique.

“Destiny. Life. Art”, as Ib would reiterate throughout his life, came with a realisation in the midst of celebration.

“For most of my time in the States,” he would tell in his memoir IB: A Life, “I didn’t even miss home. I was young and excited about everything around me. That changed with the occurrence of May 13, 1969 … I felt completely cut off. Our country appeared very far and remote — a country without any news. It was right then that I felt the need to come home.”

In what appears like an act of domiciled atonement, his return to Malaysia unravelled a period of intense productivity that settled, as if in a refrain, on tensions. Powerfully political paintings, most notably May 13th 1969 — which induced a stirring debate about the sanctity of the national flag and the creative act — emerged simultaneously with such introspective works as Aku dan Aku.

Social themes, always a principal preoccupation with Ib, this notion of “humanity”, were especially prominent at this time: the vagaries of development, wealth inequality, environmental disaster. And in so many of these paintings that can best be described as iconic is the figure of the painter’s father.

The incongruity, absurdity of modern aspirations were captured in a remark by the elder Hussein. “When I told my father I had met the first man who landed on the moon,” Ib remembers, “I thought he would be impressed, but instead he impressed upon my mind with this remark: ‘You are all crazy people. Who would want to go to the moon? There is nothing there; but there is so much suffering here!”

pak_utih.jpg

Some years earlier, these incongruities of modernity had been explored by Usman Awang in a 1954 poem entitled Pak Utih. Here the poet depicts the impoverished farmer as, “Pak Utih awaits with a prayer; all of you big men, where are you going in your grand cars?”

For a painter prone in his later life to solitude, here was an Ibrahim Hussein seeking creative synergy; for a painter inclined to the allusive, even elliptical, great also was the urging to “give utterance to his age”.

“Upon my return I often used to go to Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (the National Literary Agency) where my brother Abdullah (Hussein, the National Laureate) worked as a senior editor. There I met Usman Awang and many of the prominent writers of the time,” he recalls in IB: A Life. “One day I was with Usman and I asked him whether he knew the visual artists and he said he did not. It was always important for me that creative people should not only be working in their own studios and spaces away from the public. With Usman Awang I organised the first poets and painters exhibition.”

The pairing of Usman Awang and Ibrahim Hussein proved one of indelible discovery. In a poem inspired by the latter’s painting Aku dan Aku, Usman Awang offered, “the self is the life, life’s energy seizes the light, white whiteness a desire, the white offers it a thousand colours, the work creates painting explores, (ah, a monkey only dreams), a painter his colours are eternal”.

The Ibrahim Hussein offering was a representation (and animation) of the classic poem Pak Utih. Tri-sectional, it juxtaposes the generational “curse” of neglect and marginalisation, featuring again the figure of the father, in contrast to the scurrilous ostentation of the contemporary (notably political) aspirant. Underlined here in black stencil is the Usman Awang term used in the poem Pak Utih of Bapak— Big Man.

The painting sheds a probing shadow on the Ibrahim Hussein of our contemporary imagination — the artist who stands apart, the creator of almost all of the “iconic” paintings of our artistic landscape, yet one who hovers, seemingly, as a kind of enduring enigma. The present showing of Pak Utih remains testament to an artist of the most radical originality, temperament and empathy.

A lasting testament, surely, to the self described “Ibrahim Hussein: one blind eye, one broken tooth, one mole …”

Eddin Khoo worked with Ibrahim Hussein to complete his memoir IB: A Life, published in 2010. Rona dan Kata is currently showing at Galeri Seni Bank Negara Malaysia in Sasana Kijang, Kuala Lumpur.

This story first appeared on Apr 14, 2025 in the Edge Malaysia.