The historical thriller tells the story of Hamid, a man forced into a dangerous secret mission in 1950s Germany

If it is still possible, in this age of righteous rage and retroactive justice, to resurrect the name of Anthony Burgess, it would be best to settle on his characteristically scornful sweep of a century and a half’s worth of his nation’s history.

“British Malaya,” he writes in his dazzling collection of essays Homage to Qwert Yuiop, “was created by courageous and suffering mediocrities”.

Which might also be why the prodigious pretender to a “sentimental empire” has proved a somewhat befuddling, affectionate and, often enough, sad, even pathetic, chump.

The aspirant Sahib or Tuan is a character particular to those territories where the British sun set: V S Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas, Nirad C Chauduri’s self-parody in the lyrical if acerbic The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian and especially G V Desani’s brilliant and bizzare All About H Hatterr — the odyssey of an Anglo-Malay merchant in the midst of bustling Calcutta in search of his enlightenment — are testaments.

French, Dutch and Spanish archetypes, on the other hand, were in deep contrast, proving almost always tortured, existential and brooding in the shadow of the scorching desert or the devouring tropics.

Unlike our colonial cousins in South Asia, sometimes in Africa, and farther flung in the Caribbean, the post-colonial literature of Malaya/Malaysia, has, painfully, suffered from a terminal lack of humour. Often maudlin, overwrought prose, peppered with references to local delicacies or dress, the random lah at the end of a dialogue for “local effect”, worn down by nostalgia, has mostly been the post colonial Malayan/Malaysian literary burden. Ironically, it was a nativised Englishman, Johan Bagley — writing a weekly column, Johan’s Bag of Marbles, in The New Straits Times of the 1980s — who best carried a sardonic tradition.

confessions_of_an_old_boy.jpg

Then, decades later enters Dato’ Hamid, whose first name we hardly ever know (Joe for Johan or Johari, perhaps?), of pristine pedigree— Malay College Kuala Kangsar (MCKK)-educated and Malayan Civil Service (MCS)-trained — and fitted with all the necessary accoutrements such as pipe, cognac and cravat. He is the consummate “gentleman” with the clipped drawl and the incessant complaint of “the now”, of the Tuan Majistret variety, perfected in a dream in P Ramlee’s raucous comedy Labu dan Labi.

Kam Raslan’s Dato’ Hamid adventures — hilarious and whacky — find him often in the most exotic of places and the most quixotic of situations, such as murders, scams and other absurdities that intrude upon a life that preferred the proximity of the jungle and the tending of orchids.

Confessions of an Old Boy: The Dato’ Hamid Adventures was a novelty in the contemporary Malaysian writing landscape. It was wry, nicely absurd, free of allusions to tropical “sights and smells” and propelled a character in Dato’ Hamid that appeared suspended in time, encapsulating the early promise of self-rule and the grim realities that would later come.

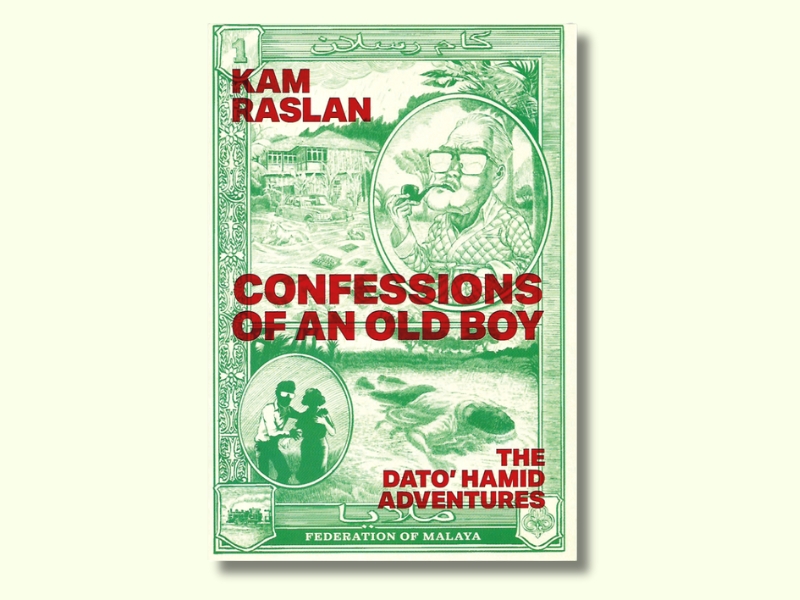

In Malayan Spy, Dato’ Hamid, fully fleshed out, finds himself “inching my way through a fog so thick I was unable to see my hand in front of my face” in the middle of London’s Great Smog of 1952 — the year that saw the death of King George VI and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Here, “sights and smells” serve as a trigger to the unravelling of Malayan Spy, only it is the “sights and smells” of modern grit — the shopping mall and Calvin Klein perfume in contemporary Kuala Lumpur. The “nighttime in my fog” stirs the journey “through the fog of my past” when the young Dato’ Hamid, then a poorly student in London, encounters, through the dank fog, Tom Pelham, the son of Sir Alfred Pelham KCMG, “the British Empire’s chief potentate in my home state …”.

The young Hamid, through a series of coincidences and encounters, finds himself in the centre of Cold War intrigues, moving from Berlin to the Soviet Union all against the backdrop of a home, Malaya, on the watershed of nationhood.

kam_raslan.jpg

Loosely a “thriller” and “spy” novel, Malayan Spy is really a taut and finely woven narrative that delicately blends its characters in a series of quirky and effective encounters. Ever present is the humour, the absurdity, but great also is a wistfulness made meaningful through the weight of history it wades through. There are evocative descriptions, and remembrances of places that give light on the deeper connections of the colonial experience, such as Malaya Hall and even the song Cheek to Cheek.

Packed with historical allusions, Malayan Spy is set in a restless age of transition between Malaya’s independence, the Cold War and all that came after. In being a novel unlike much else that has emerged from this landscape — warm, funny, evocative and full of arcane historical detail — it is quite a delight.

And in the character of Dato’ Hamid, whose first name we never quite know, is what possibility exists in all characters who we think we might have known well, only now to need to know again. If only, like Kam Raslan, we know how to write it.

This article first appeared on May 5, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.