In an interview published in The Guardian on Dec 6, 2014, Kazuo Ishiguro revealed how American singer/songwriter Tom Waits’ ballad, Ruby’s Arms, influenced him to “reverse a decision I had made, that Stevens would remain emotionally buttoned up right to the bitter end”.

Ishiguro was talking about the dutiful head butler in his 1989 Man Booker Prize winner, The Remains of the Day, a man who believed in being of service to his employer and living a life of perfect order.

Restraint, memory, regret and an underlying sadness are threads that hold up the books of the 2017 Nobel laureate in Literature, whose first reaction when the BBC phoned him to break the good news was: “Do you have any evidence if this is true?”

Born in 1954 in Nagasaki, Japan, but raised in Britain from the age of five, Ishiguro has written seven novels, a collection of stories and numerous scripts for film and television. Before devoting himself to writing full-time in the early Eighties, he worked in a London shelter for the homeless, wrote songs and played the guitar in clubs and pubs, inspired by his “heroes” while he was growing up — Canadian singer/songwriter/poet Leonard Cohen and American singer/songwriter Bob Dylan, winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Ishiguro being “flabbergastingly flattered” at being so honoured is understandable, given that the bets were on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, a favourite to win for years, Haruki Murakami — Japanese readers who had gathered in Tokyo to await his name being announced celebrated Ishiguro as their own — and Margaret Atwood. The TV adaptation of Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale — set in a dystopian world where a few remaining fertile women are forced to copulate with powerful men and bear children who are then taken away — took the Emmy award for Outstanding Drama Series last month.

London bookmaker Ladbrokes placed the odds for these three authors at 4/1, 5/1 and 6/1, respectively.

After the reality of winning had sunk in, Ishiguro told the media: “The world is in a very uncertain moment and I would hope all the Nobel prizes would be a force for something positive in the world as it is at the moment. I’ll be deeply moved if I could in some way be part of some sort of climate this year in contributing to some sort of positive atmosphere at a very uncertain time.”

Mr Stevens — Anthony Hopkins’ spot-on portrayal of the butler opposite Emma Thompson’s housekeeper, Miss Kenton, in the 1993 movie that won them best actor and actress nominations at the Academy Awards — was not one to wear his heart on his sleeve. Unlike him, Ishiguro is forthcoming, especially in his regard for fellow writers.

“Part of me feels like an imposter and part of me feels bad that I have got this before other living writers. Haruki Murakami, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, Cormac McCarthy, all of them immediately came into my head and I just thought, ‘Wow, this is a bit of a cheek for me to have been given this before them’,” he was quoted in The Guardian as saying on Oct 6, a day after the Swedish Academy named him Nobel laureate for novels of “great emotional force” that “uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world”.

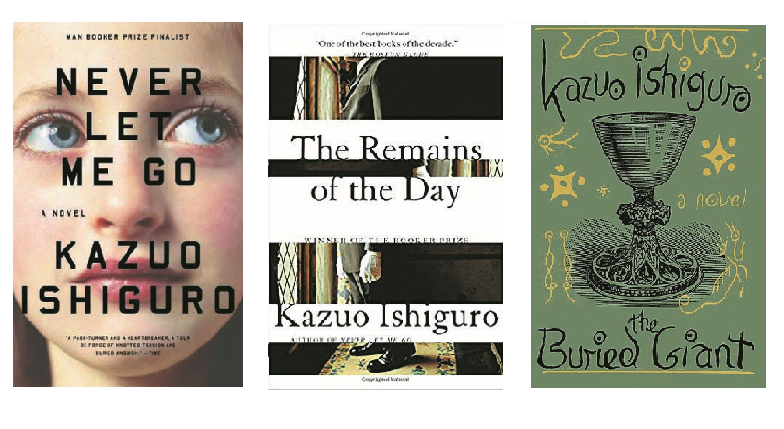

Ishiguro’s A Pale View of Hills (1982) and An Artist of the Floating World (1986) were first-person narratives set in Japan. Remains was his third book, followed by The Unconsoled (1995), When We Were Orphans (2000), Never Let Me Go (2005), Nocturnes (2009) and The Buried Giant (2015). They have won him acclaim for an elegiac, pared-down style of writing that readers find powerfully effective.

The author was gracious in his moment of glory, referring to Oct 5 as being “an important day” for Lorna MacDougall, his wife of 31 years, who was about to have her hair tinted a new colour after months of consideration when he phoned her at the hairdresser’s and asked her to go home.

That same evening, he declined an invitation to the opening night of Japanese theatre director Yuko Ninagawa’s Macbeth because “it wouldn’t be right if people were trying to interview me about the Nobel Prize when they should be remembering the great Ninagawa”, who died last year.

Ishiguro, who is said to be working on a new novel, as well as theatre, film and graphic novel projects, hopes that fame will not encroach on the time and space he needs to write. The Guardian quoted him as saying, “I just hope I don’t get lazy or complacent. I hope my work won’t change. And I hope that younger readers aren’t put off by the Nobel.”

The Nobel Prize ceremony will be held in Stockholm on Dec 10, the anniversary of the death of Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who established the awards in 1895.