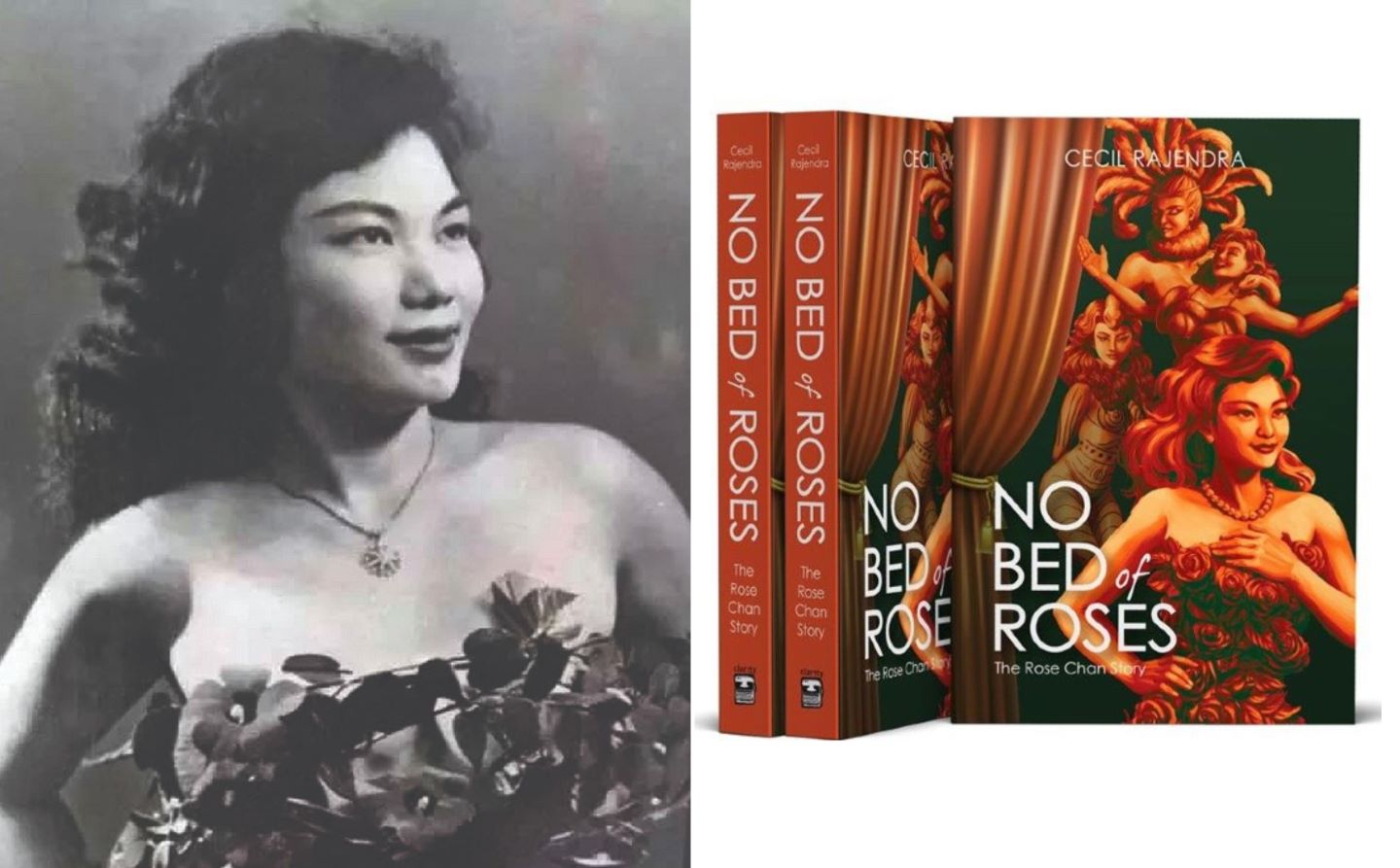

No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story was published a decade ago by Marshall Cavendish Editions (Photo: Marshall Cavendish)

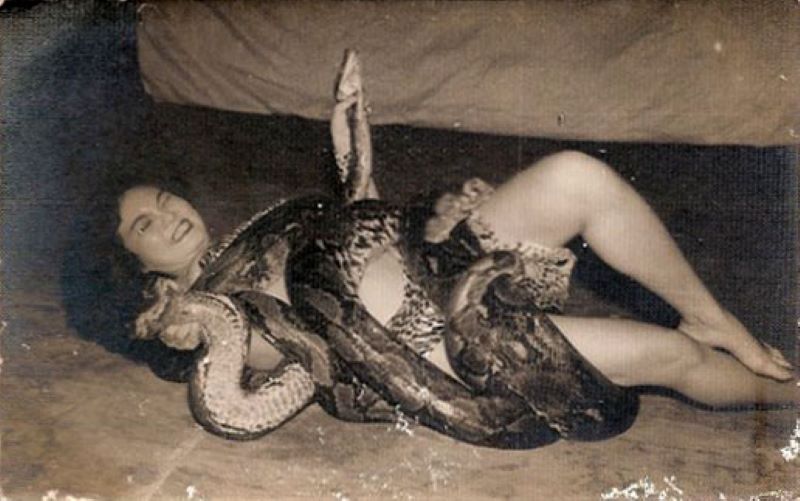

After being saved from a crushing end by Abdul, the albino python she was wrestling with at Ipoh’s Majestic Theatre in 1952, Rose Chan took the floor with renewed vigour, cheered on by the crowd. Then her bra snapped and fell, leaving the tin miners and rubber merchants seated in front stunned, as the hoi-polloi in the back rows hooted for more. Pre-planned or wardrobe malfunction, who knows?

After being nonplussed for seconds, she continued her routine “bare-breasted and with panties rolled halfway down her hips”, Cecil Rajendra writes in the authorised biography No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story, published a decade ago by Marshall Cavendish Editions 26 years after her death on May 26, 1987. A 2023 edition by Clarity Publishing, with new photos and material, hits the stores this month.

“The incident launched her career as a striptease artist,” Rajendra says at his Penang home recently. Up until that point, she had been a burlesque dancer who learnt to bend iron bars and wrestle with pythons from “Tarzan Ali”. They never performed together but he staged his acts at New World Amusement Park in Penang and Great World Amusement Park, Singapore.

Rajendra first met Chan in 1981 through Lee Khai Hong, aka Lee Ying, her manager from the 1950s. Diagnosed with breast cancer and given six to 18 months to live after a mastectomy, she returned to Penang to die. She had fond memories of the island and loved its food.

Also, she was looking for a lawyer to transfer her apartments in Seremban and Kuala Lumpur, jewellery, money and other belongings to her children so they would not fight over them after she was gone. Lee, a client of the legal firm Rajendra was with then, had suggested him.

“I have heard of her but never seen her shows. When we were about 15, a couple of school friends and I tried to sneak into New World but were thrown out by the security guard,” recalls the lawyer cum poet, now 82.

A few simple agreements took care of the transfers. Then Lee, reputedly a fearless journalist who had reinvented himself as a sharp developer, told Chan she was too young to die and suggested that they do business together, like in the old days.

cecil_rajendra_credit_yasunari_rajendra.jpg

The next thing Rajendra knew, she was in negotiations with a film company and two publishers — she mentioned McGraw Hill and Times International — and was looking for someone to write her story “the way she tells it”. Again, his name came up for the job.

In no time, Lee found a place at the Hotel Galant on Transfer Road and set up Sakura, comprising a bar, barber shop and massage parlour. The necessary licences were pending but they opened anyway and clients flocked in, drawn by his connections and her reputation. Soon, there was pressure to resurrect her dance routines and Chan, who had retired in 1976, summoned her daughter Jennifer back from Singapore to lead the Rose Chan Revue.

Revived by her return to a business she enjoyed managing, she lived another six years. “Rose was very hands-on. Even when she was dying, she took tremendous interest in making sure her pub was run properly,” says Rajendra who, together with Lee, were invited now and then for lunch prepared by Chan, a good cook.

“Slowly, her story came out, not chronologically but in episodes, back and forth. She could speak a bit of English and Malay. I spoke to her in Hokkien. She would give me press cuttings, photos and recipes she had written down. The times she felt good, she would say more and be lively. I don’t remember spending any boring moments with her even when we were not talking.”

The second lease of life transformed Chan from the downcast, bloated, middle-aged woman Rajendra first met into a glamorous bubbly hostess with an expensive wig and glittering sequined cheongsams. As he gained her trust, she began telling everyone he was the only one who could write her story. On her deathbed, she even reminded Lee to make sure it came out.

No Bed of Roses is the colourful, undiluted story of Chan Wai Chang, born on April 18, 1925, in Soochow, China. In 1931, famine forced her itinerant acrobat parents to put her on a boat to Malaya, where her elder sister Ah Choon had been dispatched the previous year. Ah Chan, as she was called, landed in Singapore, lost all her possessions and was sent to foster parents in Kuala Lumpur.

She enrolled in school at 12 but was expelled eight months later for playing truant. At 16, she married a wealthy Singapore harbour master, the first of her five husbands. When he evicted her a year later because of her adoptive mother’s greed, Ah Chan found work as a dance hostess at Singapore’s Happy World cabaret and quickly became known nationwide as a dancer par excellence.

She was the first runner-up in the All-Women’s Ballroom Championship in 1949 and clinched the same position in the Miss Singapore beauty contest the following year. In 1951, she formed the Rose Chan Revue and toured the country, earning the moniker Malaysia’s Dancing Queen. After the bra incident, she gained notoriety as Asia’s No 1 striptease queen.

“Rose was actually a very good dancer,” Rajendra says. “She watched all the old films of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers and tried to imitate them. There was a lot of art and wit in her performances. She had absolute contempt for those who couldn’t dance or sing — ‘No stannert’, she said — and stripped merely to sell their bodies.”

In 1957, Chan embraced Islam and married Indonesian Mohamed Nazier Kahar, taking the name Rosminah Abdullah. That same year, she represented Malaya at an International Striptease Contest in Paris and insured her body for 100,000 Malayan dollars. In 1958, she was invited to Japan to make a film on strip shows and train girls in the art of disrobing.

She had brushes with the law, but there was support from various quarters and good deeds: she raised funds for numerous charities by giving curative massages at a health centre in Seremban. In 1959, the Ipoh Town Council was urged not to issue her a performance permit but did otherwise, saying it was better than having “people peep into your bedroom at night”.

rosechan_snakes.jpg

Rajendra’s handling of the umpteen summonses she received for operating without a licence must have made for gleeful conversations over beer. He would go to court, hand over a medical chit saying his client was dying of cancer, and ask for an adjournment. “It was always granted.” Then he would extend an invitation from Chan to the prosecuting officer to have a drink with her at Sakura.

“None of them ever said no. She was a real legend and everybody was in awe of her.” Meanwhile, Chan would be having loh mee next to the Kuan Yin Temple nearby, waiting for him to get the postponement. She never once appeared in court.

No Bed of Roses has Chan’s recipes, such as bird’s nest soup with a sprinkling of chopped ham and shark’s fin cream soup with a splash of brandy, for that extra kick. A chapter titled Aphrodisiacs, Arcana and Accessories talks about Jade Gate exercises to control nether-region muscles, dragon rings and Burmese bells that were part of her arousal arsenal, and the goat’s eyelid happy ring, designed to drive a woman to “sexual nirvana”.

“She was probably Malaysia’s first feminist because she controlled the men — no man controlled her. She had her own shows and recruits and called the shots right to the end,” the author adds.

The “Flower of Malaya” also inspired a song by Wilfrid Thomas. Rajendra reckons that, like hundreds of young men, the British-born composer must have been smitten by Chan during a Singapore stopover and went on to pen the lyrics for Rose, Rose, I Love You. Recorded in 1951 by Frankie Laine, it was the first international chart-topper inspired by an Asian icon.

Upon hearing that Rajendra had never seen her perform, Chan recreated a couple of acts for him, with Jennifer as the star. He also remembers how, one Christmas, she arrived at his office party with a huge bouquet of roses, two bottles of Otard XO and six ravishing girls.

Chan was no beauty but “she was charismatic, articulate, buxom and attractive, more so as she got older. She had real presence, lots of confidence and was firm and strong-willed. She could organise her own troupe and ‘controlled’ the police, gangsters and underworld, generally”.

In his Dedication, Rajendra thanks Christine Chong of Marshall Cavendish Malaysia (a Marshall Cavendish Editions imprint), without whose “prompting and prodding” Chan’s story might not have seen print.

It was not published in her lifetime because she was demanding a lot of money from publishers and filmmakers, he explains. They offered her a million Malayan dollars but she wanted that amount in US currency, plus the film rights.

“Many blamed her pride and cussedness; but the lady was not going to sell herself short,” Rajendra says of the artiste who allowed him a peek into her private life.

Persistence paid off for commissioning editor Chong, who first contacted him in 1986 about a contract for Chan. Subsequently, she would call every year to ask if he had finished writing the book. In 2011, Chong told Rajendra she would be retiring as deputy head, general and reference the following year. He dug out the couple of chapters he had sketched and completed the first draft exactly 25 years after Chan’s demise.

“Every now and then, Rose’s stories would appear in the newspapers. I’m from Ipoh, so I was definitely intrigued by them,” Chong says. “Also, she was simply insistent that Cecil was the only person she would allow to write about her. I think each had respect for the other in their own way.”

Chong met Rose in Kuala Lumpur and Penang, at the hospital, both meetings arranged by Lee. “I liked to make cold calls during my time in publishing and spoke to him. Rose was always proud of her ‘baby skin’. She was already ill then but her skin was still soft.”

As for why Clarity republished No Bed of Roses, founder and editor Rosalind Chua says: “We tend to think in terms of milestones and auspicious dates, and 10 years seem as good as any to celebrate Cecil’s book and, more importantly, the icon that was Rose Chan.

“She was a woman who lived life fearlessly on her own terms despite her impoverished upbringing and the hardships she had to endure. She was an original — brave, outspoken and not one to mince words — something rare in the hypocritical times we live in now.”

This article first appeared on May 1, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.