Aerial view of Stadium Negara (Photo: Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia)

Credit for building a nation is usually given to politicians and decision-makers, those at the front line who determine its direction. The Merdeka Interviews turns the spotlight on the backroom boys — architects, engineers and artists who were instrumental in shaping the landscape of Malaysia post-independence.

In the decade after 1957, a series of buildings sprang up in Kuala Lumpur and its outskirts. These were built fast, some in months and at a relatively low cost, to establish the machinery of administration all over the country. Who were the people responsible for designing and building the now iconic structures? What was their motivation? What happened as these different groups of workers came together on the ground?

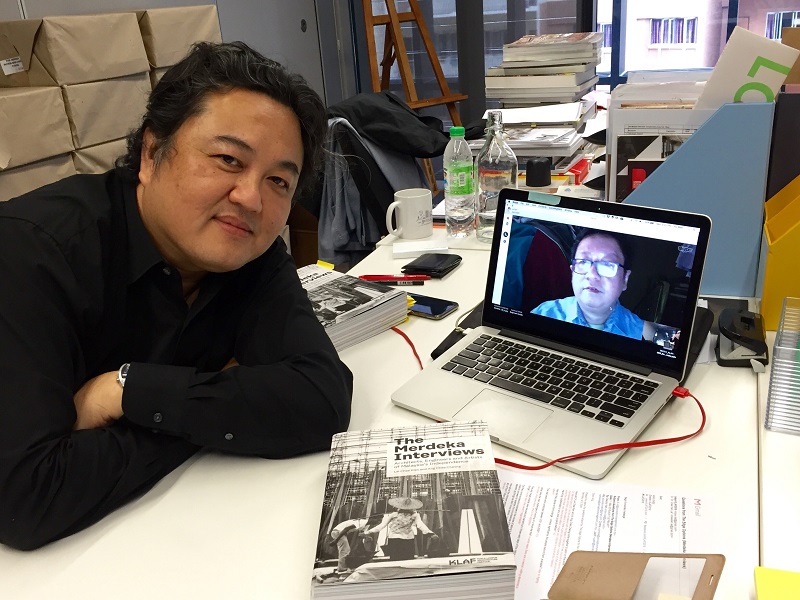

The Merdeka Interviews gets its name from the 17 architects, engineers and artists Lai Chee Kien interviewed between 2001 and 2006 for his doctoral thesis. They were the brains and brawn behind 10 projects — Merdeka Stadium, Merdeka Park, University of Malaya, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Stadium Negara, Muzium Negara, Parliament House, Masjid Negara, Subang Airport and the Tugu Peringatan.

Lai had to track down his subjects — most of them aged and some ailing — in the US, the UK, Australia, Singapore and Malaysia and spent days taping the conversations. Ten of them have passed on since, which underlines the importance of putting on record their roles and work in “shaping the architectural icons, and the milieus, circumstances and larger historical contexts during which they practised”, says the adjunct associate professor at the Architecture and Sustainable Design Pillar, Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Ang Chee Cheong, an independent architect based in Kuala Lumpur and co-author of the 668-page tome, says the period of urgent building “was a golden moment in architecture in the country, never to be repeated”. More importantly, the projects were entwined with the country’s social and cultural history as well as world politics of that time because “you cannot see the buildings without all the things that happened before”.

The interviewees are Kington Loo, Philip Chow, Ronald Pratt, Baharuddin Kassim, Hisham Albakri, Ivor Shipley, Chuah Thean Teng, Ho Kok Hoe, Waveney Jenkins, Cheong Laitong, Dudley Pritchard, Lai Lok Kun, Raymond Honey, George Atkinson, Ismail Mustam, Lee Kwok Thye and Stanley Jewkes.

The authors feel the aural testimonies enabled the protagonists to be heard in their own voices and resonances, and reveal a lot that was previously unknown and unacknowledged in the industry, such as the hordes of ordinary women and men who laboured on the muddy fields to build a new future.

The book salutes the army of tough dimunitive lai sui mui, or kongsi women, who were tasked with carrying concrete from the ground up to the structures being constructed, where it was then poured into the framework.

“That was the only way [to hoist the concrete up]. We did not even have a crane at the site,” engineer Lee, who was involved in building the Merdeka Stadium, tells Lai.

“They come to the site in black clothes, usually on bicycles. Their sleeves were extra long so that they could use them as gloves. They wore big straw hats with a hood. There were big gangs of them, each carrying two small buckets of concrete that was premixed at ground level. They walked up a ramp to take them right up to the top of the construction. A man would be up there to receive the concrete, pour it in, they’d return, and then continue in a chain system.”

Women typically made up 60% of the workforce on construction sites at that time.

Other interesting stories about the construction of the stadium surfaced from the interviews. As it was expensive to import steel for the lighting tower, the engineers got creative and strung together modified monsoon drain pipes made by Hume Industries. It was no mean feat: An engineering journal wrote that Merdeka Stadium’s prestressed towers, at over 140ft, were the highest in the world when they were completed.

The stadium was cleverly designed as an earth bowl — as the workers dug out the site, they filled the sides with the earth. Excess soil from the project was transferred to the site of Masjid Negara and various others that were going on at the same time.

Budget constraints led to a lot of discussions between Malaysia’s first finance minister Tan Siew Sin and architect/engineer Jewkes, the then head of the Public Works Department (PWD), on what the latter could spend on Stadium Negara. They managed to find some sort of compressed paper and resin used by the US air force and bought enormous stocks of these materials for the roof sheeting, says Jewkes, who drew the drafts of the Merdeka Stadium design at his kitchen table.

It was an extraordinary time and Malaysia, as a new nation, was in a hurry to get the buildings up for the national celebrations, Lai writes. Shipley, another PWD (now JKR) architect then working on the Parliament House, used to get phone calls from Jewkes saying, “The Tunku [Abdul Rahman] has had a vision. Would you please go and see him.” One of the prime minister’s visions was having a national monument to remind Malaysians about the lives lost during the Emergency. Another — “I’m sure the idea was initiated by him” — was to build Parliament House, symbolic of the practice of democracy in the country.

“A lot of developing countries did not have this kind of structure at that time and people could easily associate having it with the possibility of democracy, a space for debate,” Ang says. In the same way, the stadiums symbolised a place to groom healthy citizens; University of Malaya, an institution to educate the people; Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, a centre that offered facilities to promote the national language; and Subang Airport, the start of international travel.

These key institutions could be erected fast because those involved in their construction were all moving in one direction and they felt the buildings were something they could be proud of, Lai and Ang say. Having standard office blocks helped as these enabled the architects to map out a space and put the required structure up in a matter of months. There was also cooperation and continuous communication between the different departments and a pool of very skilled workers who moved freely from one project to another and took great pride in their work. Many of the projects involved lots of risk, which required conviction and belief in their own craft.

Knowledge of architecture can lead to a better understanding of a country, Ang believes, citing the incredible example of Masjid Negara, which was built using donations from Malaysians of all races. “I find that quite touching. Also, the site of the mosque is where the Anglican chapel and graves used to be. You could never do that today.

“There was no cynicism, no suspicion then. People were just committed to a common vision and purpose. With the new mood of the nation, I think we need to grab that back. I think what happened on May 9 provides the perfect opportunity to re-evaluate how we should go on from here.”

This article first appeared on June 11, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.