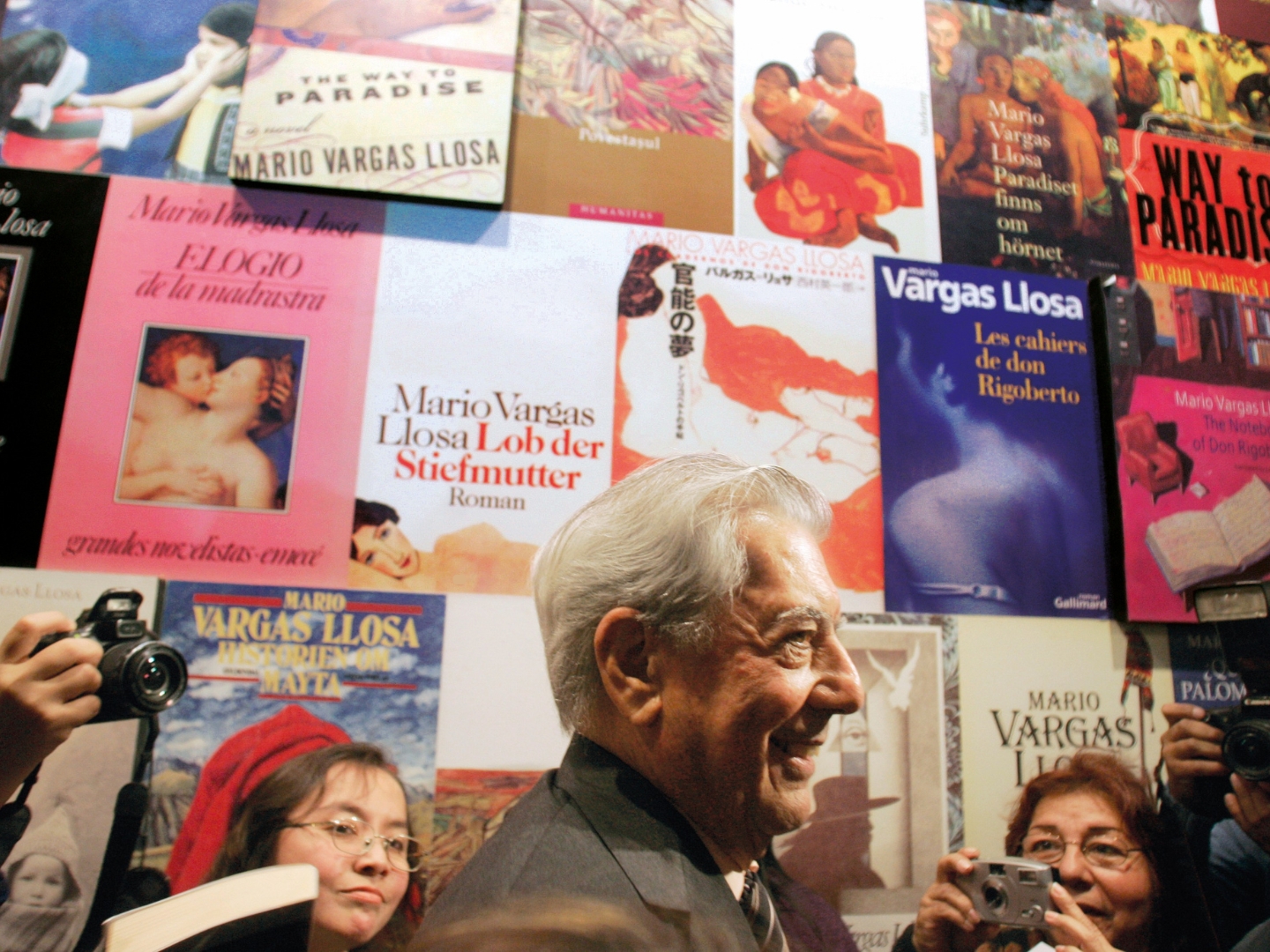

Vargas Llosa surrounded by people during Mario Vargas Llosa, the Freedom and Life, an exhibition of his works in Lima, Peru (Photo: Reuters)

“We invent fictions in order to live somehow the many lives we would like to lead when we barely have one at our disposal.” — Mario Vargas Llosa

Fidelity, infidelity, poverty, place and power must have settled as a keen sense on Mario Vargas Llosa from his very birth since they served as preoccupations — literary and political — all through his “heroic” life.

Born in Arequipa, Peru, a land surrounded by three volcanoes and adorned with colonial Spanish buildings crafted from sillar, a white volcanic stone, he entered the world to a young mother who wept at the recitation of Pablo Neruda’s lyrical Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada (Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair), and a father he did not know until much later.

For all the capacious imagination that infused Vargas Llosa’s novels, his most remarkable literary testament may well be his own remembrances. In his memoir A Fish in the Water, stark in its intriguing autobiographical truth, he recounts his parents’ early separation, upbringing amidst a gregarious grandfather and uncle, introduction to a fake father, and vivid journey — described in such detail that it transcends the limits of recollection — to meet his real father.

Fatherless, the young Vargas Llosa forges the deepest bond with his mother, while harbouring a stirring adolescent resentment towards his father. Spending a night at Chiclayo, a seaside town before returning to Lima as a family put back together, he recalls, “They left me in a room and locked themselves in the one next door. I spent what was left of that night with my eyes open and my heart pounding with fear, trying to hear a voice, a sound from the adjoining room, dying with jealousy, feeling that I was the victim of a monstrous act of betrayal. At times I found myself retching in disgust, overcome by an infinite loathing, imagining that my mama might be in there doing those filthy things with that stranger that men and women did together to have children.”

Such prose, rippling with the picaresque, would come to epitomise the style that came to be known as magical realism. That style, which inspired the Latin American literary boom, was described by Vargas Llosa’s long-time amigos a enemigos (friends to foes), Gabriel García Márquez, as “all real, no fantasy — it was the life lived”.

mvl_nobel_crunchy.jpg

A restive family life, inner resentment, growing up in a climate of political authoritarianism, the young Vargas Llosa was enrolled, early, in La Salle, a famed school run by Jesuits. Later, he was admitted to a military college — an experience he despised but which created the ferment from which his lifelong hatred for authority and his inveterate commitment to human freedom would be forged.

Like many aspiring Latin American writers, Vargas Llosa entered the world of journalism at the age of 15. In a Peru and Latin America dominated by military administration and puffed-up dictators, he would gather all the details of power, vanity, absurdity… necessary to fuel his, principally, first novels. In 1963, he would publish La ciudad y los perros (The Time of the Hero) in Spain. It centred on a murder and a cover-up at the Leoncio Prado Military Academy where he had studied, and explored the farce and injustice perpetrated by the privileged. It aroused such resentment among the elite in Peru that 1,000 copies were burned on the school’s parade ground. Vargas Llosa’s commitment to journalism, however, remained unshakeable, and he continued, voluminously, to write journalism and essays with a forceful political slant, most notably in a long-running column in Spain’s principal newspaper, El País.

His literary beginnings were remarkably romantic. Encouraged by his grandfather, who steadfastly believed in his genius, he pursued his goals despite once thinking, “My childhood dream seemed totally impossible — to be a writer”. Determined to commit to his aspirations, he travelled to France. As he recounted in his delightful Nobel lecture, “In Praise of Reading and Fiction”, his reading was cosmopolitan — spanning William Faulkner, Charles Dickens, Thomas Mann, Joseph Conrad, and especially French authors like Honoré de Balzac and Gustave Flaubert. The latter became the subject of a spirited and insightful study, “La orgía perpetua: Flaubert y Madame Bovary” (“The Perpetual Orgy: Flaubert and Madame Bovary”). Extended stays in cities like Madrid and London followed, leading Vargas Llosa to graciously confess, “I owe my writing life to every city I have lived in”.

Paris was a special place since, in that most exquisite of literary paradoxes, he remarked: “In France, I became a Latin American” during a lecture at the 92nd Street Y in New York in 2007. His discovery, not just of Latin American writers, but the region itself, was not only a literary watershed; it proved also a political one. Like many writers of his generation, with literature came an involvement in politics. Vargas Llosa’s early flirtation with Marxism ended in disillusionment over the Fidel Castro regime’s repression of political dissent in Cuba. This ideological fracture was to result also in a deep divide in personal friendships, most notably with García Márquez.

Their infamous punch-up, resulting in García Márquez sustaining a black eye, was forged into a part of Latin American lore. Even the revered journal, The Paris Review, published a sassy “gathering of voices” from among writers, translators and friends about what “might” have happened. Politics, women, rivalry — or a combination of all three — might have been the reasons but the general consensus among them was how Vargas Llosa, with his swashbuckling good looks, could have landed the decisive punch on Gabo, who was built like a prizefighter.

Whatever the real reason, the political fissure made the greatest impression. Lamenting the poverty and corruption in Latin America, Vargas Llosa began a series of deliberations which affirmed his faith that only the free market could ensure prosperity for Latin America and an escape from the shackles of poverty and dereliction. He expressed admiration for the free market reforms of former US president Ronald Reagan and especially former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher, writing the latter an effusive letter of praise.

In 1989, he took the plunge and presented himself as a candidate for a coalition of right-wing, free market parties for the presidency of Peru. Successful in the early rounds, he lost to Alberto Fujimori, who later adopted many of Vargas Llosa’s free market reforms before ending up in prison for corruption and embezzlement. It seemed that Peruvians did not wish their literary hero to be stained with the dirt of politics.

mvl_books.jpg

A period of dismay following this loss ensued, and Vargas Llosa poured lyricism and sentiment into some of his finest, yet arguably underrated, novels. These include El sueño del celta (The Dream of the Celt), a powerful and poetic imagining of the Irish revolutionary and diplomat Roger Casement, and the intense, polyphonic El Paraíso en la otra esquina (The Way to Paradise), revolving around the Peru years of painter Paul Gauguin. Yet, even as political bitterness subsided, his political convictions abated not, and a series of strange and reactionary positions led The New Yorker to run an article titled, “The Puzzling, Increasingly Rightward Turn of Mario Vargas Llosa”. A later realisation was that the literary would always prevail. And just prior to his passing on April 13, Vargas Llosa wrote at length about returning to the grand literature of the classics, including Miguel de Cervantes and his much-loved Flaubert.

In his prose, Vargas Llosa always set himself apart by blurring the lines between high seriousness with the playful, the erotic and the titillating. A reading of his delightful novel La tía Julia y el escribidor (Aunt Julia and the Scripwriter), a part autobiographical, part surreal lift-off from his first marriage to his aunt (related through nuptial ties), who was 19 years his senior, remains testament of his packed versatility.

“I learnt from my political experiences that I am a writer, not a politician,” he told The Guardian in 2012. “Part of the reasons I have lived the life I have is because I wanted to have an adventurous life. But my best adventures are more literary than political.”

In writing his own epitaph, Vargas Llosa might have gotten himself in the writer’s trap of omission by forgetting the word “delight”.

Adventure and delight — two words that sum up the complete Mario Vargas Llosa experience best.

This article first appeared on Apr 28, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.