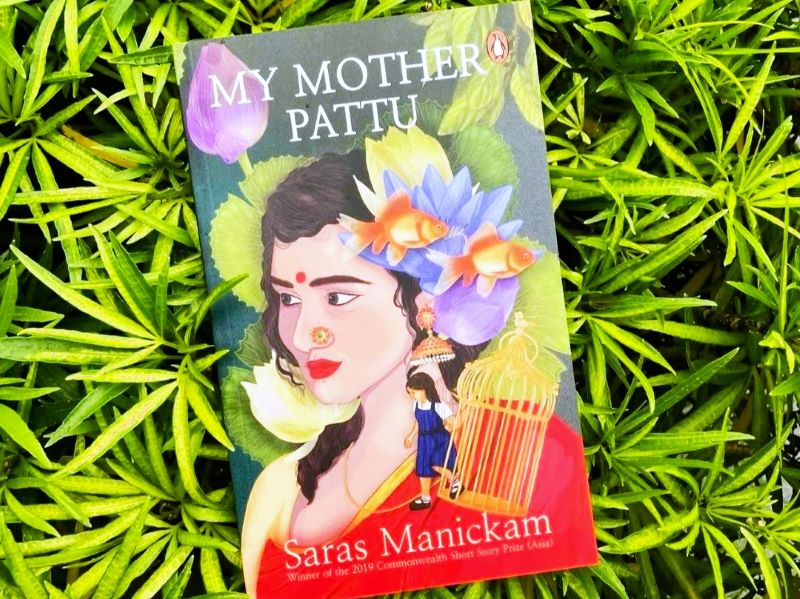

Saras Manickam’s first book is a collection written over nearly two decades, and features her 2019 Commonwealth Short Story Prize-winning entry as the titular story (Photo: Saras Manickam)

Options: My Mother Pattu won the 2019 Commonwealth Short Story Prize (Asia). What led to its birth?

Saras Manickam: Growing up, I’ve known women like Pattu — strong, independent women who struggled against convention, patriarchy, made their own choices and sometimes paid dearly for them. They were larger than life, colourful, bold, not always allowing moral scruples to get in the way of life. I wanted to write about them and how they impacted the lives of everyone around.

The person who began to write this story was very firm in her convictions: Pattu was horrid, mean, monstrous, and she had to be suitably punished by the end of it. It didn’t work at all (and so took 10 blinking years) because the author was trying to manipulate storyline and character. The author decided she knew what was best and so the story kept falling spectacularly flat.

It was only when I learnt to let go, to let the characters chart their own story that My Mother Pattu began to take shape. The voices became authentic. Later, when it was published in Granta and many people read it, I received comments such as, “You’re writing about my mother”, or “I know that woman — she’s my grandma”.

The opening para is riveting. Is Pattu based on someone you know?

I do love the opening paragraph, though we’re not supposed to say that about our own work. It is almost perfect — sometimes you just get lucky. Having said that, I wrote dozens and dozens of drafts. I’m so embarrassed to even admit it but I’m half sloth and it takes me ages to write, let alone complete a story. Still, the person who wrote the first draft of My Mother Pattu was not the person who wrote the last line of the last draft. There’s an inevitable metamorphosis of story and writer. Life happens: you work, you cook, you love, you grieve, you grow up and grow kinder, more compassionate, more mature. You’re no longer interested in a moral soapbox. More importantly, you learn to let the characters tell their story.

Did Penguin Random House SEA approach you with an offer to publish?

I approached them with a completed manuscript of 14 stories. When My Mother Pattu won the regional prize, I realised it was time to stop dithering. I’d attended a couple of creative writing workshops with [writing coach/editor] Sharon Bakar in Kuala Lumpur and numerous Prague Summer Programs for Writers run by the amazing Richard Katrovas and Stu Dybek. When I was still not published as yet, the Château de Lavigny [an international residence for writers in Switzerland] gave me residency space. I was the first non-published writer they’d invited. Maybe I was the first and last.

It was time to honour my craft, honour my teachers who’d been generous with their time, space, knowledge and experience. I had to stop giving excuses and start serious writing. However, Covid and the Movement Control Order made me even more sluggish and it took some years before I had a collection for submission. Some of the stories have been published before. I tweaked them and wrote new ones.

my_mother_pattu_book.jpg

On top of your work as teacher, teacher-trainer, copywriter, Business English trainer, copy editor and writer of textbooks and school workbooks, you write fiction. When and how did that start?

No, no, this makes me out to be an English Language Ironwoman! I worked as a teacher, then teacher trainer, and on leaving government service after some years, went into copywriting. I was writing schoolbooks, workbooks and co-authoring three textbooks for the longest time. I wrote stories, yes, at night, but apart from some getting published, most failed to get even a nudge from anywhere. No, not surprised; they were awful. But I kept writing and reading and reading even more and reading still more. Writing, not so much. I also tried to stop manipulating characters and story to show off my brilliance. Then I did Sharon’s writing classes — that was the trigger. Later, I attended the Prague programme and the sessions shaped me enormously as a writer. I hardly write schoolbooks now or any other writing. The focus is on fiction.

How did you pick these 14 stories from the many you have?

It was easy. Some of my earlier stories were utter rubbish. I stuck to the ones that had been published and were decent. Then I worked on my newer stories (and reworked and reworked them) and wrote a couple of newer ones.

Why short stories? How about a novel?

I can only write short stories. I’ve tried novels but my lack of attention, focus, discipline and zero mathematical ability to keep track of movement, character, setting, plot and so on make it rather difficult. My attention flags easily.

Any favourite story or author that has impacted you?

I’m learning from the greats! P D James, Dorothy Sayers, Ruth Rendell. Elizabeth George’s earlier Lynley novels. Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache series. I love them all. I read and reread them, for the sheer pleasure of it all firstly. After that, I read for the craft, to study how their creative imagination fills your head and heart. They are intellectually satisfying and emotionally, there is all this heart, this understanding of the human condition. I read Preeta Samarasan for her mastery over the written word, her razor-sharp insights; Tash Aw, who is simply a wonderful writer; and Tan Twan Eng, whose lyrical prose just sweeps over you. It’s always about the language and how language speaks of our lives, revealing layers, facets. I also stop reading a book if it ceases to be interesting.

Are there themes you constantly explore or touchy topics you have been able to broach through fiction?

Patriarchy, child abuse, racial discrimination. Treatment of working-class immigrants as sub-human, except that it subverts to how the immigrants’ own families view them back home. The list goes on but what I like to think is that above all, the stories are deeply humane, that they haunt with their searing honesty. People are complicated and these stories explore the complications without authorial judgement.

How has your craft changed since your first short story was published?

Dey Raju was my first story to be published after I began writing somewhat seriously. It was light, fun with undertones that spoke of communal assumptions and practices. It poked fun at the narrator’s comfortable assumptions. Since then, I’ve grown (I like to think so). My writing is fairly honest, unsentimental, and I strive for an authentic voice. The stories explore patriarchy, abuse, disabilities, ageing, racism, discrimination. and ‘affirmative’ action. In Call it by its Name and When We Are Young, to mention two, the characters confront not just other people’s or society’s shortcomings but one’s own racism, discrimination, bigotry and prejudices. I think it’s necessary to acknowledge victims can also be perpetrators and perpetrators are also victims, of history and social realities.

Charan and Will You Let Him Drink the Wind talk of physical and mental disabilities and both are searingly honest, brutal even. In many of the stories, there is an element of the narrators or main characters facing up to or acknowledging their own roles in their perceived victimhood, for want of a better word. These stories are all lived experiences, even if they may not be all my experiences. They strive to be unsentimental. I can’t and won’t do sentimental.

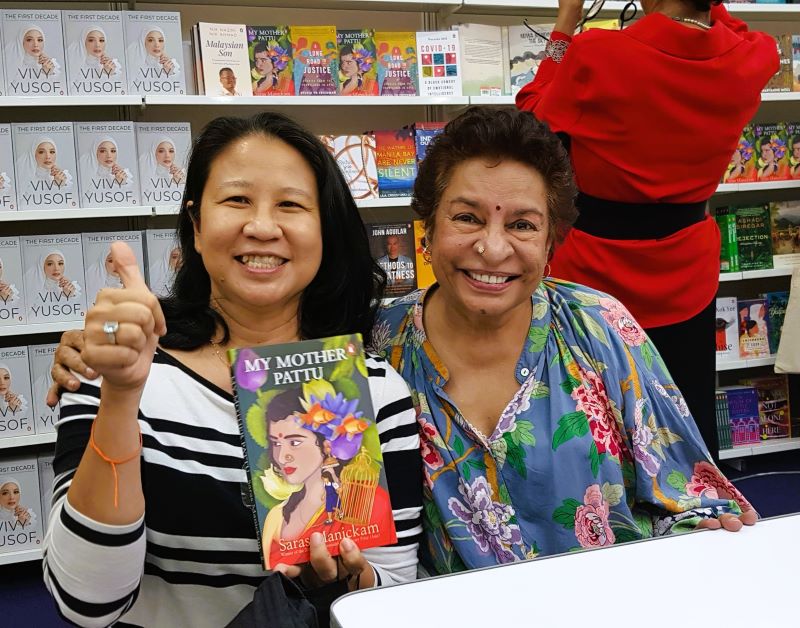

shih-li.jpg

You advocate writing classes. How do they help the new writer or someone struggling to improve?

Creative writing classes are essential for everyone, not just writers. The exercises help release blocks from the mind, the heart, strip away layers of comfortable notions, help the writer face herself. They release the imagination from self-censorship; they make you step up because writing, good writing, demands nothing less than honesty and a willingness to be unafraid. You give yourself permission to be your authentic self, scary as it may seem. Then you learn to actually discover that authenticity. There’s an enormous energy, a dynamism in a good creative writing class where you learn, absorb from your peers and mentors; where you learn to be fearless in confronting your own work so you can make it better. You learn to step out of yourself.

What are you reading now?

I can’t write a line of detective fiction but I adore crime writers, especially British writers who explore character in depth as much as the crime itself. I love Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache series set in Canada — she teaches me so much. I’m reading Brotherless Night by V V Ganeshananthan, about the civil war in Sri Lanka. It’s utterly compelling.

Any plans for a second collection?

My middle name is Sloth, remember? I’m writing. That’s what I do. The stories will, as they always have, take shape slowly until they tell me they are done.

Any ‘lessons’ that may help those who aspire to write?

I’ve received enough rejections (still receive them regularly) to paper an entire wall. Rejections utterly crush you — for a while. You cry, rail against editors who cannot see your brilliance, tell yourself you should have stuck to teaching because at least you’ll have a pension. Then you get up, sit back at the computer and get straight back to work. Because: You are a writer.

One thing I’ve learnt is to avoid interfering in the story.

The moment I interfere in the flow or how the characters ought to be, say or act, the story stops working. The only thing to do is trust your characters to tell the story themselves. You strip yourself of your own self-censorship, prejudices and opinions, and let the story take you where it will. I keep forgetting this, which accounts for the gazillion drafts.

Six regional winners of the 2023 Commonwealth Short Story Prize are vying for the overall prize, to be announced on June 27. They are Hana Gammon (South Africa, Africa), Agnes Chew (Singapore, Asia), Rue Baldry (UK, Canada and Europe), Kwame McPherson (Jamaica, Caribbean) and Himali McInnes (New Zealand, Pacific). Malaysian author Shih-Li Kow’s Relative Distance was among the 28 shortlisted entries for the prize, awarded to the best unpublished short fiction from any of the Commonwealth’s 56 member states. Submissions for 2024 will open on Sept 1. See here for details.

This article first appeared on June 26, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia