Long rediscovered joy in the forest after grieving the loss of her husband for a long time (Photo: Suhaimi Yusuf/The Edge)

Old trees stand at attention like guardians, their canopy casting a shadow over the forest. Wood, pine and damp earth create an elusive bouquet of scents perfumers would struggle to bottle. In this sanctuary of fresh air and filtered sunlight, the silence broken only by the wind or birdsong, Long Litt Woon studies the mossy ground.

A decade ago, the idea that she would someday prowl through a forest hunting for fungi would have had her in stitches.

“Mushrooming was not something I would have been drawn to, no. It’s too quiet, too slow. I was a consultant and ran my own company. I was very efficient, always go, go, go. But then (my husband) Eiolf died suddenly and everything changed,” says Long.

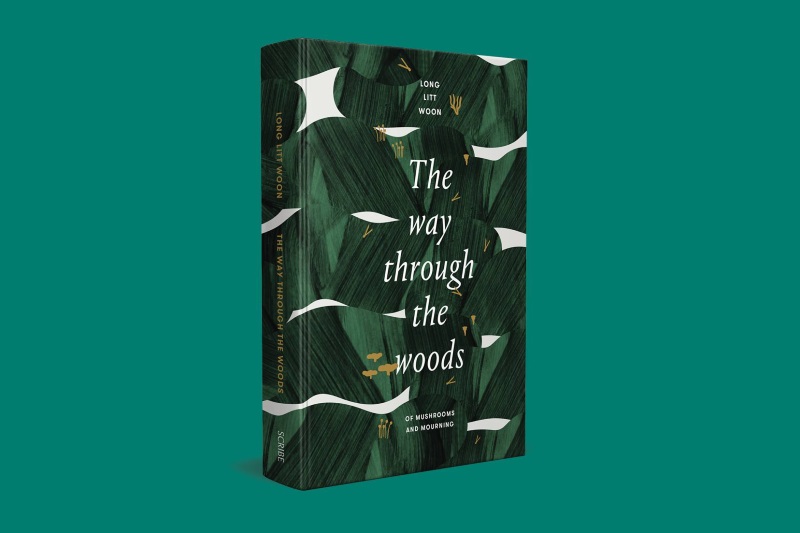

The Taiping-born anthropologist now calls Oslo home, but is in Kuala Lumpur on a quick book tour shortly after The Way Through the Woods: Of Mushrooms and Mourning was released in English. Despite the morose premise, an inevitable consequence of inserting the act of grieving into the title, the debut memoir is a delightful read, brimming with hope, astute observations, a quirky cast of characters and all things mushroom, including recipes.

the_way_through_the_woods.jpg

“He just went to work and didn’t come home,” says Long. “I needed more time to grieve than people were allowing me. Society’s attitude to death is sanitised and brisk, not so much in Malaysia with the Chinese ceremonies and traditions, but certainly so in Norway. The whole process is stripped to the bare minimum, geared towards the funeral, and then it’s over. You’re meant to just pick up and carry on but I was devastated … I had a complete loss of identity. Losing Eiolf meant losing my life witness, the person who can verify the things I had gone through. We grew up together, were very much a part of each other. Although we were extremely independent and had our own friends and interests, it all happened side by side. So, yes, it was a big shock, and I was desperately alone and sad. I joined a bereavement group and people were doing things like yoga, meditation or travelling to help themselves.”

Seeking an outlet for her grief, she came across an introductory course on mushrooming. “I was only mildly interested. It’s not like I was wild about mushrooms,” Long shrugs, but her bright expression bespeaks the truth she would find on this incredible, if unorthodox, adventure.

forest_-_long_litt_woon.jpg

The practical course took students out into the forests to forage for and identify mushrooms, and it was in the shadowy quiet of nature that she rediscovered joy. Oslo is ringed by forests, so the last stop of any public transport service to the city’s outskirts would deliver you to the edge of one, says Long. It might as well be a new world entirely as the bustle fades into a tableau of old, lush greenery.

Part of the charm of mushrooming was the nature of the activity. While some people tackled it as a group, she preferred foraging alone in silence and leaving whenever she was tired. The pure concentration on the task at hand, too, reduced the world to a scope no bigger than a gilled fungi.

“All your senses are pulled into identifying this single mushroom,” says Long. “I wrote a whole chapter on smells because the aroma of a mushroom is as distinct as a fingerprint. You can’t tell from farmed or store-bought varieties, but wild mushrooms have discernible aromas and concentrating on this was like being woken up from a deep coma. I had become almost numb after Eiolf died, as if I were walking around in a fog and people were speaking to me from a great distance. But finding and correctly identifying my first edible mushroom … It was like being given an intravenous shot of multivitamins. As I wrote in the book, ‘All at once a slender, golden beam of light pierced my soul.’ It was a very concrete and immediate reaction, and I knew I would stay on this path. It was the only thing that brightened my life, gave me this unexpected feeling of euphoria. I thought I had lost joy forever.”

mushrooms-_long_litt_woon.jpg

As her knowledge of this curious new world advanced — she is now certified by the Norwegian Mycological Society as a mushroom expert — she toyed with the idea of documenting her experience. Rather than a nature guide that could be used as a reference, the notion of a quirky memoir of sorts appealed. She wanted to work Eiolf into the narrative, as he was the impetus that led to this, but struggled to find the link between the two in a literary project. So, she simply started writing.

“I ended up writing not about death but about the loss of him,” says Long. “Death is a form of loss but there are many other types, which I think people can relate to. You can lose a job, your health or your country if you are a refugee. Any time you lose something central to your identity, it forces you to redefine yourself — who are you without it? You have to find your bearings again. This book has been described as a love story, but my husband dies on page one. As I was writing, I realised that this would be about two interconnected journeys: That of an outer journey, my discovery of the kingdom of fungi, but also an inner journey into the landscape of grief.”

The Way Through the Woods took about four years to complete and was published in Norwegian in 2017. Translations and distribution to over a dozen countries followed, enchanting readers with trivia (edible and poisonous varieties), fun facts (a 19th-century Norwegian mycologist was so fixated by the field that he changed his last name to Sopp, or “mushroom”), anecdotes (the unnatural depth of her interest only dawned upon her when she declined to attend a friend’s wedding in favour of a mushroom fair) and a motley crew of obsessive foragers who fiercely guard secret locations of mushroom colonies, completely oblivious to life beyond fungi. The New York Times declared the book “moving and unexpectedly funny”.

talking_about_the_way_through_the_woods.jpg

“I’m an anthropologist, so it seemed unavoidable that as I was learning about mushrooms, I was also observing the people around me,” laughs Long. “I noticed the culture of mushrooming, the heroes, the villains, the dos and the don’ts. And then, what do you know, I became one of them. I have this moment in the book when I realised I had started off on the outside looking in and then suddenly asked myself, ‘Have I become part of this?’ Meanwhile, the journey of grief starts in blackness and didn’t happen linearly: It was always one step forward, two steps back. I wanted to reflect both processes as they happened, so the two journeys unfold simultaneously.”

Writing The Way Through the Woods was not intended to be therapeutic but it had that effect. “More than anything else, it helped me organise my thoughts,” she says. “When I first lost Eiolf, I thought about him 24/7. Now, some time can go by without me thinking about him. There’s no guilt in that. He’s still with me, just in a different way. I think of him fondly and I’m very grateful for the time we had together. And I think if you have gratitude that the glass is half full, you are not at the same time whining that it is half empty. I don’t know how he would have reacted to the mushrooming and the book, but I think he would have said it was typical of me to do something like this.”

Talk naturally turns to the occupants of her mania and, of course, she has a favourite. “The variety I love best is the true morel. It’s incredibly difficult to find. After discovering social media, I once posted some true morels I had found and the top gourmet restaurant in Norway immediately contacted me to see if I would sell them. I thought, you cannot pay me what I want, I’m keeping them!” she laughs. “You can find them in gourmet stores. They are expensive but are so potent that you don’t need much, just one will do. My next favourite is maybe the agaricus genus, from the same category as the button mushroom, but the wild ones taste 10 times better.”

forest_finds.jpg

Tips and recipes pepper the pages but she shares a basic rule of thumb in person. “The easiest way to prepare mushrooms, even store-bought ones, is to put slices in a pan on medium heat and leave them there without any fat or oil to let the moisture evaporate,” says Long. “It intensifies the natural flavour. Only then do you add the fat. If you put them in with the fat, you’re basically going to boil the mushroom. I like cooking and thanks to mushrooming, all these new ingredients and methods have suddenly opened up to me.”

She travels the world now to talk about her field of expertise and book, but in the quieter moments at home, you might chance upon her in a Norwegian forest, gazing intently at the ground. “It feels like there’s a bubble, and it’s just me and the mushrooms,” she says. “Nothing else matters. Time stands still. It’s just this … This being in the moment. It changed my life.”

'The Way Through the Woods: Of Mushrooms and Mourning' is available at Kinokuniya for RM69.90. Buy here.

This article first appeared on March 2, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.