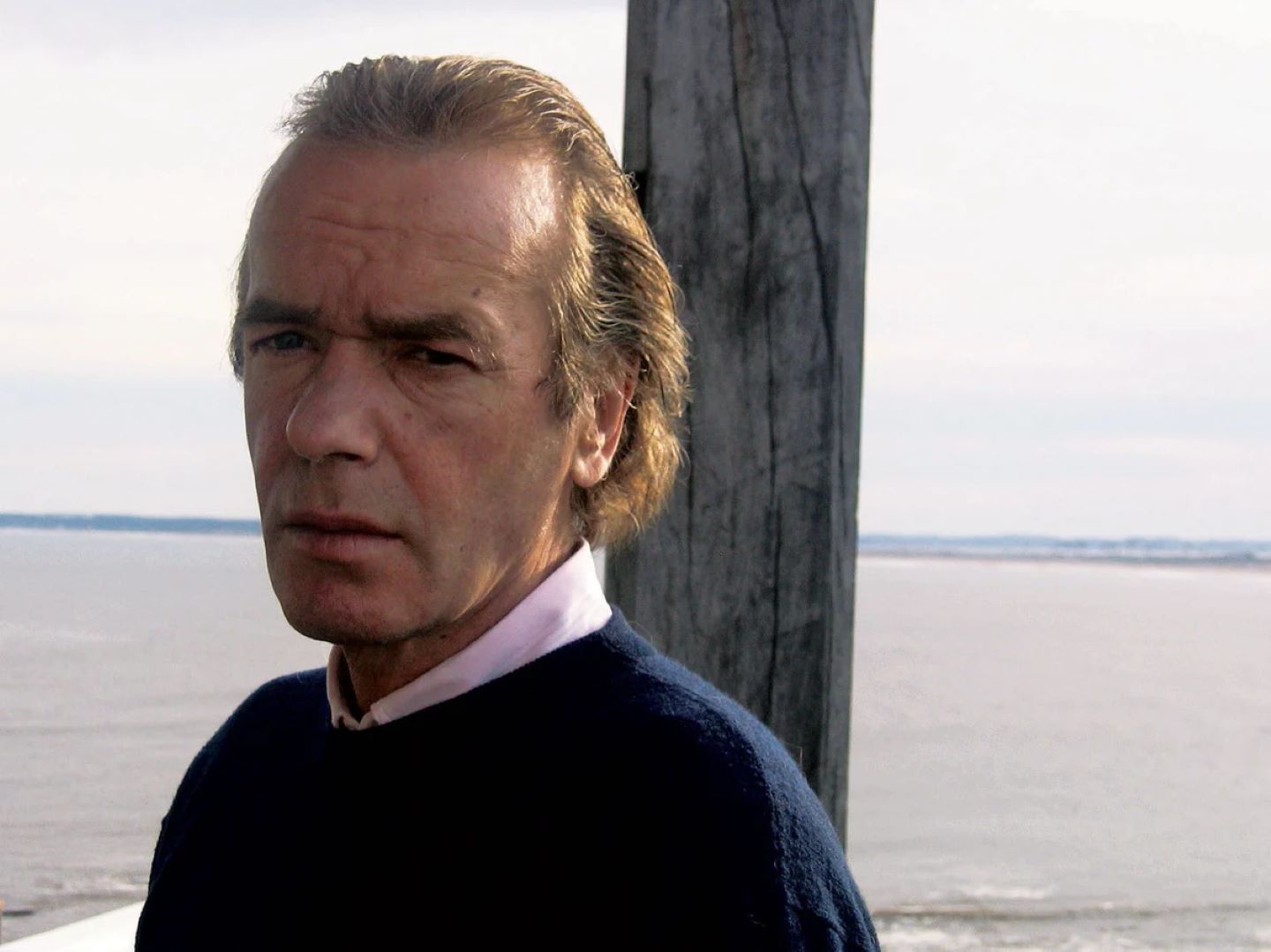

Amis was an English novelist, essayist, memoirist, and screenwriter (Photo: Reuters)

Even the most animated imaginations have their limitations. Perhaps it is a matter of climate.

For all of Martin Amis’ forays into history, and the darker recesses of the “human condition”, the farthest venture into “hot country” for him was settling, quietly, in Lake Worth Beach, Florida, where he died on May 19, 2023, from esophageal cancer, aged 73.

Kuala Lumpur would have been an inspired setting for an Amis novel, an unexpected contrast to the background of his other novels set amid rain, sleet and snow. Or perhaps the stark contrast of tropical shadow and light might have been too obvious for a writer with a particularly caustic sense of the comic, and a ceaseless allure for the opaque.

Kuala Lumpur, the now never-to-be setting for an Amis novel, served nevertheless as a cautionary tale of how not to write about his writing obsession — monsters.

Bigger Monsters. Little Monsters.

Speaking of exploring the nature of “monsters”, the “study of evil”, Amis once said: “I think you have to distinguish between the big monsters and the little monsters: those with a big stage to act on and those with a little one. They breed each other. When you look into the big historical monsters, you expect — when you open the biography of Stalin or Hitler, or Mao — the first sentence to go, ‘He was raised by crocodiles in a cesspool in Kuala Lumpur,’ as if this would explain what then followed.”

Perhaps the one singular aspect that distinguished Amis from his fellow “celebrity” generation of writers was that he lived out the caricature made of him (and which, for quite some time, he lived up to) relatively early, retreating, especially in more recent times, into deeper contemplations of language, style, form — the “stuff” of writing.

Following his death, Amis has been described as “era-defining”, with little proper interrogation of what that era might actually have been.

The tabloids anticipated a heightened news cycle that has since gone mad: Screen celebrities and the royalty still offered very much, but not quite enough.

The British media, in particular, shifted its gaze to a rising generation of novelists — loud, contrarian ones — not so much to invest tabloid-ism with a touch of the intelligent but to remind tabloid-ers that the “intelligent” could pretty much behave as badly as any of us.

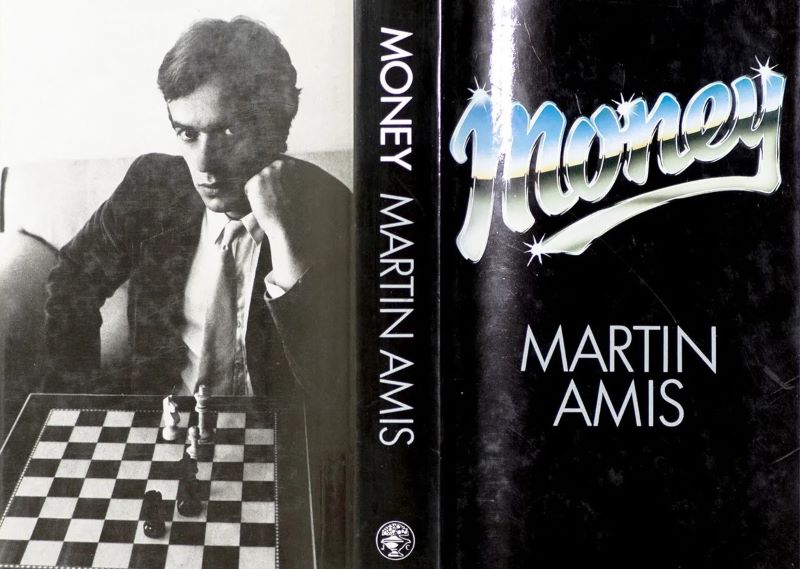

The magical chaos of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children; the sharp, acerbic political invective of Christopher Hitchens (even Mother Teresa was not spared); the decadence of Ian McEwan — all captured and anticipated the near-nihilism of a new political world, dominated by rising corporatism, and captured most vividly in Martin Amis’ Money. No one, it would seem, could have lived through the 1980s without having read Money or, at least, have lived enough.

money_book.jpg

Thatcherism defined this generation, but in stark contrast to the writers across the Atlantic emerging from the twin ideology of Reagan-ism — Richard Ford, Don DeLillo; remote, morose, even grumpy — Thatcherism spawned flair, outlandishness in her generation of contrarians.

Dinner parties, chasing after women, a love-loathe attraction to Margaret Thatcher, who was once described by French president Francois Mitterand as having “the eyes of Caligula, and the lips of Marilyn Monroe” — a remark often picked up by Amis in his reflections on Thatcher.

All of this literary tabloid-ism peaked with long expositions of rival love lives, friendships fractured (in the case of Amis, when he dropped his long-time agent Pat Kavanagh, the wife of his friend, the novelist Julian Barnes, for Andrew Wylie, widely referred to in the literary world as “The Jackal”), culminating in a long, scurrilous exposition of Amis’ expensive adventures in a dental chair. “All for a Liberace Smile?”, said The Observer when referring to the affair in a review of Amis’ invocative and bawdy memoir, Experience.

“I enjoyed the interaction,” he reflected several years on.

Perhaps the falling of fatwa on the head of his friend Salman Rushdie brought about a sense of anticipation, even prescience. Interviewing Rushdie, following his emergence from hiding, Amis was to write, in wry terms, “Salman had disappeared into the world of block caps. He had vanished into the front page.”

Intuition, or prescience, or simply the need for self-preservation as a novelist, to not morph into the parody and caricature that both his closest friends Rushdie and Hitchens were to become — the former and his obsession with celebrity culture; the latter adopting silly political positions and ending with a juvenile war against God.

Prescience; or perhaps just a sense that the Little Monster needed to become the Bigger Monster.

Future Amis novels and writings would attempt to venture into the world and psyches of Stalin (in Koba the Dread), the Holocaust and Mohammad Atta (in a New Yorker story imagining the last few days of one of the hijackers of the second aircraft that crashed into the Twin Towers on 9/11).

The most lingering monster, though, might well have been the spectre of his own father — the renowned novelist, author of the classic novel Lucky Jim and sometimes poet, Kingsley Amis. The father-and-son relationship was close, if sometimes fractious, especially as the older Amis adopted reactionary political positions and made — in that classic British phrase — “the piss take” an art form. The younger Amis would escape into the world of literary fathers —Vladimir Nabokov and Saul Bellow (whom Amis fondly called “the tortoise”).

kingsley.jpg

In later life, the likeness between father and son would manifest physically — the slight shuffle, the modest paunch, the gradual melt in the fact. Once asked what the greatest influence of Kingsley was on Martin Amis, the reply was terse and unambivalent: “Dedication.”

“My father was also a poet, which I am not,” he would often recall in interviews, perhaps the most lasting statement of the later Martin Amis, searching for the Bigger Monster — the poetic line.

To a question on how to write the perfect line, he says:

“The process is saying the sentence, sub-vocalising it until there is nothing with it … This means not repeating the same sentences, its suffixes and prefixes — if you have a ‘confound’, you can’t have a ‘conform’; if you have ‘invitation’, you can’t have ‘execution’. You can’t repeat the ‘-ing’ or a ‘-ness’— all that has to be one per sentence. And I think the prose will give a sort of pleasure without your being able to tell why. That is what I hope.”

This article first appeared on May 29, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.