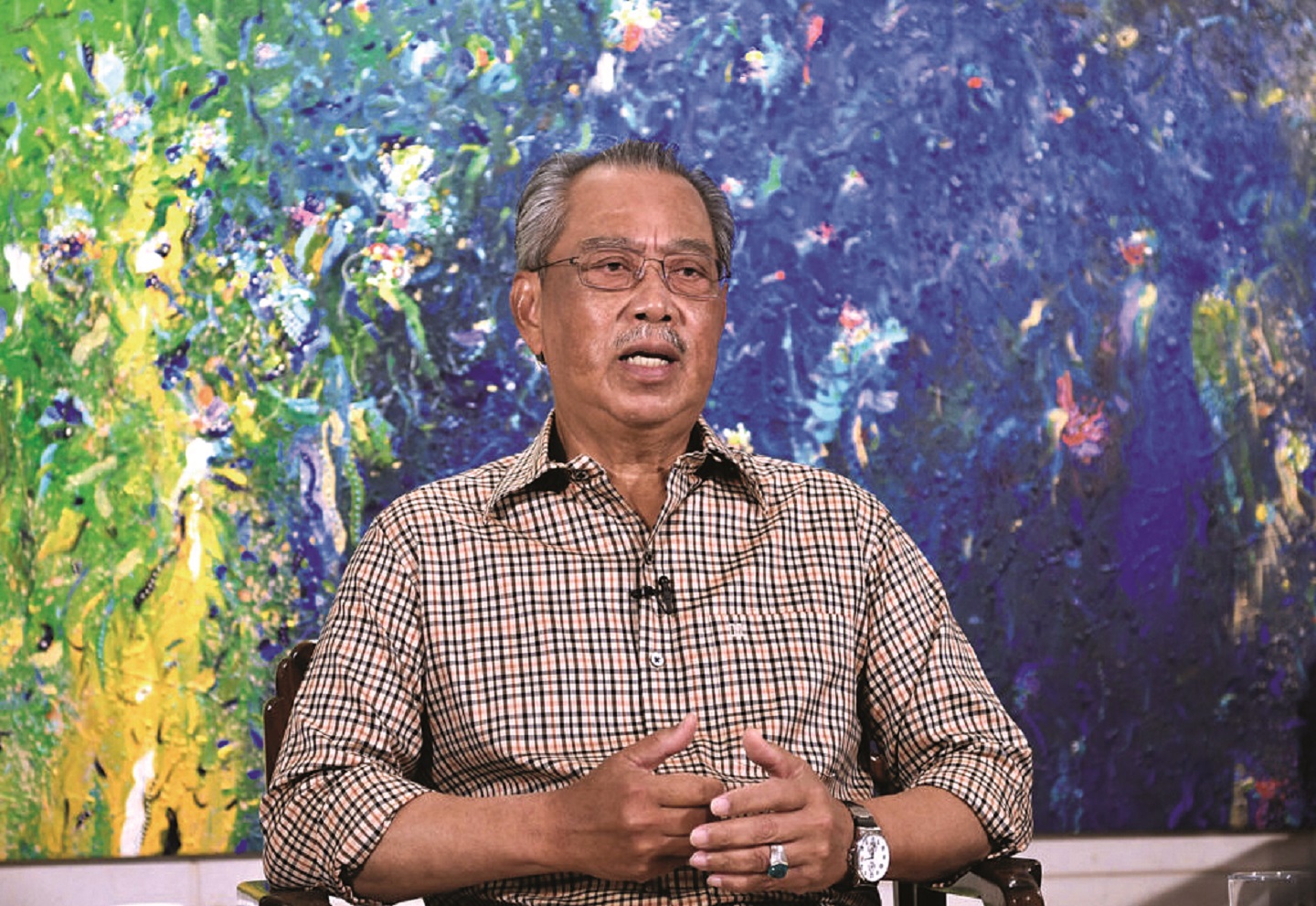

Tan Sri Muhyiddin, with Ismail Latiff’s painting behind him

When the US’ President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping addressed the 75th UN General Assembly remotely in September, they had at least one thing in common — both had large artworks in the background.

President Xi had a stately painting of the Great Wall of China at dawn. The fiery mountainous landscape contrasted with Trump’s softer and more elegant set-up in the oval-shaped Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House. The familiar portrait of George Washington hung in the centre, while parts of the famed panoramic Zuber & Cie wallpaper Scenes of North America — chosen by Jacqueline Kennedy — were also visible.

The pieces caught the attention of Malaysian art collector Pakhruddin Sulaiman, leading him to muse on social media: What would our own prime minister use as a backdrop for his address, if he were to do it remotely?

The question was answered two weeks later, when Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin underwent self-quarantine for the second time after one of his cabinet ministers tested positive for Covid-19. As he gave a perutusan khas, one could see a colourful abstract painting by Ismail Latiff, likely from his personal collection.

Art and politics have had a long relationship, to say the least. Political art has become increasingly prominent in our media-saturated world today, used as much for visual expression as a tool for politicking. Still, there has been far less light shed on our politicians’ taste for art.

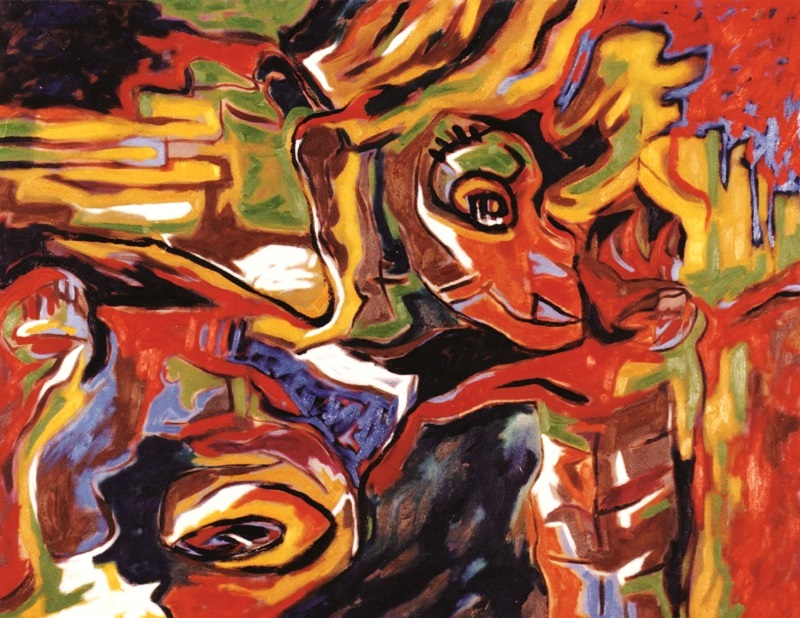

semangat_alam_1.jpg

Ismail, for one, is well-regarded as one of Malaysia’s veteran artists, a modernist painter who is close in age to our prime minister. Bingley Sim, another prominent local collector, says of the choice: “It is certainly pleasant and easy on the eye. At the least, it adds an atmosphere of vibrancy and warmth to an otherwise boring and dreary wall.”

Writer-curator Jamal Afiq Jamaludin offers a more pointed observation. “The aforementioned is a senior but not ‘super senior’ artist. That would mean that, one, the work is not particularly exorbitant or luxurious. Second, it is an abstract, non-figurative work that can still be deemed Islamic enough for a Muslim to display at home. Third, it’s interesting that a political figure of such stature went with an artwork that had no overtly Malaysiana or nationalistic context.”

His third point underscores the insights one can glean from the choice of artwork. Artist Ahmad Fuad Osman certainly thinks so. “Your house and interior, with all its furniture and objects, speak louder than you’d think, especially when you’re a public figure and, above all, the prime minister. For me, his choice to give his speech in front of the artwork neutralised his position and, in some ways, he avoided more personal scrutiny with such a backdrop.”

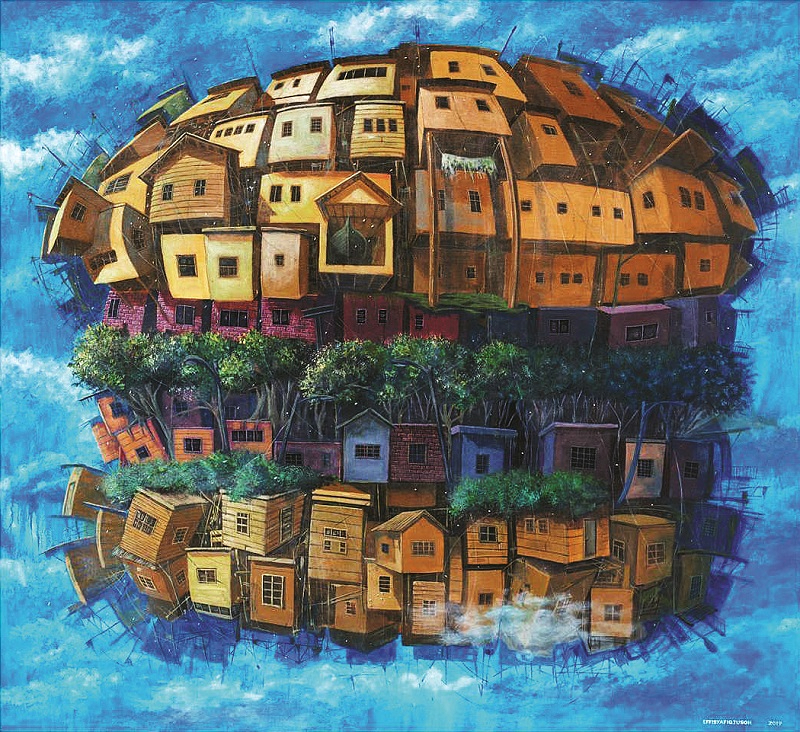

What about other Malaysian politicians? Pakhruddin also pointed out Finance Minister Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Aziz’s ownership of Muhammad Effi Shafiq Jusoh’s 2019 work, High-Performance Foods (Delicious), which was priced at RM5,800. It was seen on TV1 during a news segment. The young contemporary artist specialises in sculptures and paintings featuring a theme of houses with a decidedly urban slant.

54800043_419784525491865_3878386194484035584_o_1.jpg

Minister of Foreign Affairs Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Hussein would naturally opt for art with more nationalistic themes. For Merdeka Day, in a video recording session in Wisma Putra, he stood in front of an art piece featuring the Malaysian flag. But perhaps more intriguing is a glimpse of what looks like a painting of a traditional Malay warrior hanging in his office.

Curiosity aside, gallerist Sophia Shung believes that no matter whether the artworks are staged or otherwise, any sort of proselytising for art and culture is a good thing. “Particularly when these leaders show their preference for Malaysian art. It shouts loud and clear, ‘Who else to count on if Malaysians do not support Malaysian art?’”

In the bigger picture of things, Shung says the visibility also invites a relook at the attitude that art is not important in times of crisis, albeit more subconsciously so. “Politics divide, but art binds,” she adds.

Pakhruddin takes a more cautiously optimistic view. “I don’t believe art can change the world. Its role is more secondary in nature. But what it can do, and does, is provide awareness about our condition and situation.”

“And it can portray the image of a forward-thinking nation moving towards a more cultured, intellectual and first-world mind frame,” Jamal says.

Fuad, who is known for a body of work that often intersects with the realm of politics, nevertheless recognises the significant role art can play in political settings. “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth — that is the law of propaganda often attributed to the Nazi, Joseph Goebbels. Art has been used as a tool and even weapon throughout history, be it posters, paintings or even monuments. Of course, it depends on the type of work chosen, but art has the power to shape people’s minds and their views.”

This article first appeared on Nov 2, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.