One of the most famous NFT collections today is the Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), whose investors include talk show host Jimmy Fallon, musician Future, music producer DJ Khaled, rapper Eminem and most recently, actress and entrepreneur Gwyneth Paltrow (Photo: Bored Ape Yacht Club)

The melding of the art universe and that of non-fungible tokens is something that took off in 2020, and things have grown exponentially since. While it is not the same as buying a painting and hanging it on your wall, an NFT does have this in common with traditional art: it is exclusively owned by the person who acquires it, only that its format is a unique piece of digital data. While any asset, in theory, could become an NFT, so far, it has been associated with art, and at a distant second, music and videos.

The nomenclature is fascinating, to say the least. Artists do not make NFTs, they “mint” them on a blockchain which is done by combining a base (usually Ethereum), a digital file and “smart contracts” (codes that interact with the blockchain). Artists minting their artworks refer to the act of “tokenising” — uploading the artwork to a marketplace and issuing a digital token to guarantee its authenticity. Buyers and collectors watch digital art marketplaces such as OpenSea, Nifty and SuperRare like hawks for new “drops” (or launches) and will immediately place bids, trading in multiple currencies.

What is most interesting about NFTs is the community you suddenly become a part of and the connections made with buyers, creators and influencers from all over the world. In fact, the purchase of select NFTs sometimes comes with invites to exclusive discussions on sharing platform Discord.

NFTs are not tangible pieces of art and this certainly raises some concerns, but if Sotheby’s is into these, there must be something to it all. The centuries-old art auction house earned US$100 million from NFT sales last year. It held its first NFT sale, produced by the digital artist Pak, from April 12 and 14, which brought in US$16.8 million from 3,000 buyers. Since then, Sotheby’s has sold an NFT of the original World Wide Web source code for US$5.3 million, a rare CryptoPunk worth US$11.8 million and a collection of 101 Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs for US$24.4 million, among others. So successful was its foray into this blockchain-based digital asset explosion that it launched its own curated NFT platform called Sotheby’s Metaverse last October.

Malaysia has its own NFT players too; but unfortunately there is glaringly little data on the scene. Here’s where they stand.

Art makers

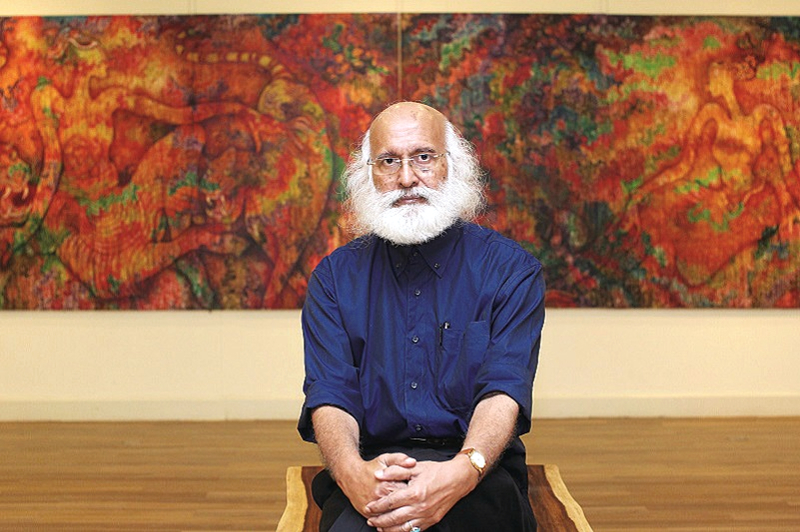

Although not the first Malaysian artist to mint some of his art as NFTs, veteran artist Syed Thajudeen Shaik Abu Talib is definitely the oldest at 78. His brightly toned Kebaya series was the first to be uploaded on local NFT marketplace Pentas, as he wanted to have some sort of ownership over his works. It also means that he is able to establish a relationship with his buyers, who can now include much younger art aficionados who can better afford NFTs.

20180312_peo_syed_thajudeen_1518_izw_edited.jpg

Operating out of his home-based studio in Petaling Jaya, Thajudeen — known for his mural paintings of epic proportions set in period landscapes — worked with his son Syed Fazal to select the pieces that would go online. An engineer, Fazal was in the process of digitally documenting his father’s entire oeuvre when the possibility of making a bit more money through NFTs came up. Almost immediately after the works went online, they were snapped up — internet-savvy art lovers could not resist the chance to pick up a Syed Thajudeen for 0.08ETH (about RM802). It ordinarily would have gone for RM12,000, the normal price of a 1ft by 1ft piece from his Kebaya series.

“I don’t really understand NFTs but I like the idea of being in contact with the people who buy my art,” the Penang-raised Thajudeen says, relaying his point in a combination of Malay, Tamil and English. “I also like the direct dealings, which is good for younger artists. They don’t need to pay galleries a big commission, they can directly access the buyers. My style is art on canvas but their style is digital art, so this platform is good for them.”

The appeal of NFTs to artists is their transparency. Not only do transactions cut out dealers but since anybody can buy an NFT, the prices of artworks sold — generally, a thing of mystery in high-end commercial galleries — are a matter of public record. Every time an NFT is resold, its creator also makes a profit — an in-built royalty system missing from the physical art world, where artists often feel as if they have been shafted when their creations are resold on the secondary market. Thajudeen, whose works date back to the 1970s, heartily agrees with this.

“With NFTs, when the art sells again, the artist still gets something. Last time, the artists didn’t get anything,” he says, frowning. “With NFTs, I know that the creators are the master, which should be the way. Some galleries take 60% from the artist, and this is too much. The artists have no say, and with all these modern technologies, the power comes back to the artist. Money also comes back to the artist, which is important — this is how we make a living. We go through so much to produce what we do — we go to art school, we study hard, we put our heart and soul into what we do. Surely we deserve some recognition? With NFTs, I really think artists will have this, which those from my generation missed out on.”

kebaya_lady_4_7.jpg

Thajudeen’s foray into NFTs is minimal compared with the more established efforts by the likes of Munirah Hamzah, Katun (aka Abdul Hafiz Abdul Rahman) and Red Hong Yi, whose recent exhibition Memebank was featured in Options. Admittedly, Thajudeen’s works do not quite lend themselves to the more digitised nature of what sells in NFT marketplaces these days, but they have sold out, and quickly — meaning that traditional consumers of art have the potential to be led into the new world when their shepherd is an artist they trust.

A stage for Malaysian NFTs

Together with four other like-minded tech enthusiasts, Irsyad Saidin co-founded Pentas to advocate and educate the public on blockchain technology, with a focus on bridging and highlighting culture and heritage through digital art. Its NFT marketplace, pentas.io, is an extension of this aim, operating as an enabler for local creators and artists to display their art. Based in Doha, Qatar, until the pandemic hit, Irsyad moved back to Malaysia in 2020, and with the work-from-home arrangement during the lockdowns, met his future collaborators on Clubhouse to establish Pentas. Meaning stage in Bahasa Malaysia, it is the first locally-based NFT art marketplace.

“In early 2021, we noticed NFTs start to really grow and we saw the potential. NFTs are all about art now, but if you know the technology, you can see how it can be applied to pretty much anything, like ticketing systems for example. Our plan is to set up our company, launch a marketplace for art and see how things go,” says Irsyad, who has experience in cryptocurrencies. “I am glad to say that our team of five has all the necessary skills in various business-related aspects.”

Their timing couldn’t have been better as the hunger for a local NFT marketplace was at fever pitch — within just 30 days of the Pentas marketplace going live, more than RM1 million worth of NFTs were transacted. It has been an upward journey since, Irsyad says. “We didn’t expect to grow this fast — the plan was to just make sure there wouldn’t be zero transactions,” he admits. “We registered 3.3million page views over the last 28 days, with a high percentage from Malaysia and the US, and each person spends about eight minutes on our site.”

img_6486.jpg

It is not to say Irsyad and his team have not come up against any challenges, though. Intellectual property remains a key issue going forward because in most countries, a creative work must be the original creation of an author and it must be reduced to material form to be eligible for copyright protection.

However, the actual artwork that the NFT creator mints may be protected by copyright. Hence, the basic rule is that NFT creators can only mint artwork that they own the copyright to, to avoid any infringement.

Irsyad and his team have put in place several measures to protect the rights of both buyers and artists, including report functions and stringent verification processes for parties at both ends of the equation. “We are very strict about KYC standards, and we apply it thoroughly,” he says, referring to Know Your Customer, protocols designed to protect financial institutions against fraud, corruption, money laundering and terrorist financing.

Another major challenge is Pentas’ use of Binance, which has come under fire from the Securities Commission Malaysia for illegally running a digital asset exchange in this country. That created what Irsyad calls a perception issue, not a legal one.

“What people don’t get is that Binance is an exchange and we are only using its blockchain network. There is a misconception that if you buy anything on Pentas, you will get into trouble with the SC, which isn’t true. We opted to use Binance well before the SC’s announcement came out, and for good reason — it’s the third ranked cryptocurrency in the world behind Bitcoin and Ethereum, and its market cap is huge.” At present, buyers use Kucoin to acquire BNB — Binance’s cryptocurrency — for trading purposes.

nfts.jpg

On the content side, things are a little clearer for Pentas. Although it was initially hard to get artists to sign up for the platform, a few cleverly positioned incentives made the decision easier and eventually led to a snowball effect — both art makers and buyers quickly came on board. “In 2021, we traded BNB1,800, which worked out to RM4 million,” Irsyad says proudly. “Right from our first month, we have been a profitable, sustainable business.”

The NFT marketplace is just part of the ecosystem he and his team are building, which he hopes will soon be able to serve communities across Southeast Asia. Pentas’ immediate plans are to include more Thai and Indonesian artists.

“The plan is to go into music, ticketing systems and multiple other things,” Irsyad says eagerly. “But the future … I think Pentas can almost be like Instagram, in that you can upload your pictures onto the platform, and if there’s a possibility to be traded, why not? What if there is a better version of Instagram or TikTok, powered by blockchain, with the content owned by you? It’s not an e-commerce site like OpenSea, for example, but more of a content sharing site — we want people to stay longer on Pentas, and I think that will result in many more revenue streams in the future. I feel this is already happening in a way, because the time that people spend on Pentas indicates that we simply aren’t like other marketplaces. We have so much more potential.”

Gallery perspective

In the same way quartz watches disrupted the Swiss watch industry in the 1970s, or how smartwatches needled its side when they came out more recently, traditional art galleries are not about to disappear because of NFTs. But gallerists do need to be aware of what is going on and how to work around the technology in a way that best serves the needs of the artists they represent.

Scarlette Lee, founder and director of contemporary art space Core Design Gallery, agrees. “I believe NFTs will prompt galleries or even stakeholders within the fine art community to start looking at ways to make the traditional ecosystem more robust. Art galleries with physical spaces like ours still have a very important role to play in the art ecosystem, and there is also much room for improvement such as a strongly curated exhibition, strategic documentation system and professional art management, and definitely stronger digital branding programmes to achieve a more international standard — while NFTs is an interesting way forward for galleries to create more awareness of the current system.”

scarlette_lee.jpg

An art gallery’s role of supporting new artists or nurturing talent is what is missing on the NFT scene, which means a melding of the two would be a positive development, should it happen one day. “The role and effort of galleries in developing current or new talents, refining the skills of craftsmanship right up to the support system to showcase a curated body of works contextually should not be undermined. Instead, galleries should embrace the change, especially after the pandemic, which has directly or indirectly forced us to open up into the digital sphere,” Lee says. For example, during last year’s lockdown, the gallery put up an online live stream of an immersive installation by Ain Rahman, which resulted in physical visits once it was safe to do so.

“The idea of merging the current art gallery system with NFTs is extremely interesting. It’s a matter of figuring out the mechanics and resources to pump into this initiative moving forward,” she adds. “As from the current generation of collectors’ point of view, it is an exciting idea for many of them. However, physical art as an asset class is still very accessible. So, it may take some time for them to be receptive to the idea of keeping their art in some cloud server and occasionally, taking it out to admire on their computer or phone. The newer generation of collectors will most likely be more accepting of the new form of collecting, which is digital art, as they have grown up in this digital era where the possibilities are infinite.”

Although Core Design Gallery isn’t playing the NFT game yet, Lee is paying close attention to its growth, acknowledging how it is becoming a defining trend for a younger group of Malaysian artists of various inclinations. “There has been a paradigm shift between the previous generation and subsequent ones. Millennials have grown up in the digital era, so they understand, mingle and engage in everything digitally. Currently, they are possibly the largest online consumer. That is why NFTs fit this market’s needs very well.

core_design_gallery_2.jpg

“I think NFTs are a great way forward to create awareness of the possibilities of different kinds of art — even a Twitter post can be sold through the digital platform,” Lee says. “Malaysia has many creative talents, especially the younger generation in various fields of art, be it fine art, graphic design, events, photography, architecture, interior design and so on. NFTs offer the possibility of a platform for these talents to be discovered. As for those who can sell very well in the NFT space … What is most important is whether it is sustainable for those selling well currently and how to move forward.”

We ask Lee to provide us with a prediction from her vantage point as a gallery owner, and she is cautiously optimistic — a healthy middle ground, we must say. “NFTs are definitely here to stay and will continue to expand as more people want access to them and be part of the scene. I just cannot say how long the hype will last. Similar to an online platform, as it grows bigger and bigger and more accessible, it can keep surprising us.”

This article first appeared on Feb 7, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.