Vayssières consulted historians, archivists and librarians in her pursuit to bring overlooked women back to the forefront (Photo: Patrick Goh/The Edge)

Throughout history, many talented and powerful women who made an impact in their time have been overshadowed and forgotten. They should be known and their stories heard, says French artist Zoé Vayssières, who showcases their names through sculptures and performance that also prompt questions about what we choose to remember and why.

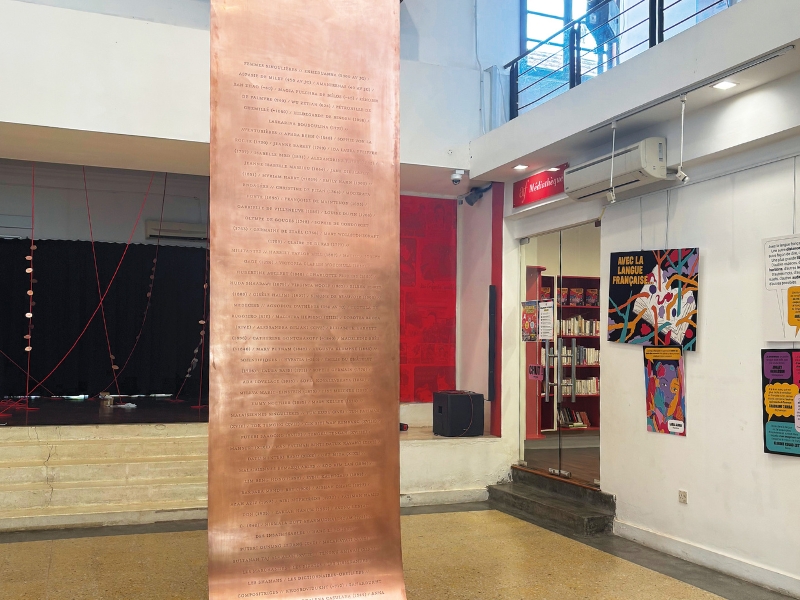

Currently on show at Alliance Française de Kuala Lumpur (AFKL), Les Éclipsées — French for “the eclipsed” — wraps up Vayssières’ two-week artistic residency in Malaysia. It reveals the names of 100 women spanning 43 centuries, among them 30 from the country, engraved on a copper plate. Another piece of work has names strung to red ropes, signifying the strong lines that connect women.

Les Éclipsées, an ongoing series Vayssières started eight years ago, is so called because, like the shadow cast on Earth when the Moon gets in the way of the Sun’s light, eclipsed women have had their contributions or achievements obscured or omitted from records altogether. Driven by her obsession with memory and time, Vayssières brings the overlooked stories of poets, authors, composers, scientists, doctors, artists, photographers, activists and local women to life through her art.

At performances in public spaces, performers are asked to trace, in chalk, names of unknown women dug out from archives. Kneeling on the streets to do so is akin to unearthing the sediment of memory, she says. But the impermanent medium is a reminder of how unrecognised achievements and contributions can easily be wiped out.

Inscribing names on copper installations is meaningful because the convective material used in telephone lines denotes the idea of communication, she adds. Also, shine a strong light on copper and words on it will “disappear”. But when the light changes, they reappear, like what happens during an eclipse.

zoe_perfomance.jpg

Before any residency, Vayssières will approach archivists, historians and librarians to ask, “Who are the important women in your history?” From the traces, imprints and memories she gathers, she then opens new lists that have grown little by little.

For input on Malaysian women from the 15th to 20th centuries on her list, she is grateful to Melaka-based historian Serge Jardin, Daniel Perret of the French School of the Far East, author Heidi Shamsuddin and Salina Zawawi from the Sarawak State Library, among others.

“I am inspired by women. When I do my lists, very often one woman leads to another, who then leads to [the next]. These lines already exist. I think we are just one long thread, and we need to think about the women of before and transmit their stories to those of tomorrow.”

She hopes that talking about the remarkable things those from yesteryear did will inspire people to “open their minds a bit” and realise there are all sorts of ways to achieve what one wants. “The way women think is really different and super interesting.”

The women she has met from digging through archives and the spectrum of what they represent is astounding, not least the many firsts they charted. After an uprising drove Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad and priestess of the Sumerian capital in Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) out of her homeland, she wrote Sumerian Temple Hymns, the oldest text by a known author.

Madeleine Brès (1842-1921), the first French female doctor, faced one obstacle after another in her pursuit of medicine, from legal barriers to resistance from a faculty dean, needing her omnibus driver husband’s consent to register for a course, and being called “a dubious being, sexless … a monster”.

Laskarina Bouboulina (1771-1825), a naval commander and owner of a shipping company, raised the Greek flag, which she created herself, up the mast of her warship, Agamemnon.

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) who, despite chronic depression, wrote classics such as A Room of One’s Own and The Waves, also left readers this profound quote: “Suppose, for instance, that men were only represented in literature as the lovers of women, and were never the friends of men, soldiers, thinkers, dreamers; how few parts in the plays of Shakespeare could be allotted to them; how literature would suffer!”

zoe_copper_scroll.jpg

Among the singular Malaysian women on Vayssières’ list is Tun Fatimah (16th century), the first Malay woman to rule her people as a sovereign queen, who reputedly was more feared by the Portuguese than her husband, Sultan Mahmud Shah.

Che Siti Wan Kembang, the legendary warrior queen of Kelantan, fought on horseback with a sword. She never married and abdicated after ruling for 57 years from 1610, passing the mantle to her adopted daughter, Puteri Saadong.

Che Mida, the Perak entrepreneur who owned mines in Salak, may be lesser known than Mahsuri, who cursed Langkawi Island for seven generations before her execution after being wrongly accused of adultery, but one can just imagine these ladies holding their own among men in the 19th century.

Women who made significant imprints more recently include Lim Beng Hong (aka B H Oon,1898-1979), the first Malayan woman admitted to the English Bar and first female representative in the Federal Legislative Council; war hero Sybil Kathigasu (1899-1948), who fed information to the underground Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army during WWII; Aishah Ghani (1923-2013), the country’s first female senator; and Zakiah Hanum Abdul Hamid (1937-2019), who served as the first female director-general of the National Archives Department and helped set up various museums.

Besides legendary figures such as Hang Li Po and Puteri Gunung Ledang (both from the 15th century), Vayssières has “nameless”, untraceable pirates who sailed from the Strait of Malacca to the coasts of Borneo; merchants who manned market stalls from Kota Bharu to Kota Kinabalu; shamans who passed their knowledge from one generation to the next, and “pillow dictionaries” — local women from whom colonists learnt the language but did not wed.

“Even if it’s legend, if people wrote those stories, there is some truth in them, I’m sure. I think these are very important women too, specifically in Malaysia, [who] carry the knowledge and important values of the country,” the artist says.

Asked why she chooses to focus on women in her work, she says: “I think I do this because I had, like, a duality at home. My mother was a feminist from the May 1968 protests in France, a revolution [centred around] the status of women: They wanted to have bank accounts, go to work, to school and have more freedom.”

Vayssières’ maternal grandmother, on the other hand, was a woman of her time with no bank account, unable to work and had to have her husband sign papers for her. “So, I had these two women and two different cultures. I love them both and think I’ve taken the middle ground, with one leg in each.”

What she grasps with both arms is knowing that “nothing is impossible. What those forgotten women went through, their crazy stories … I think if all the little girls knew what a woman like paediatrician Brès did in her time, they would say, ‘Well, I can do it too’. It gives you strength, opens your mind and you start thinking everything is possible”.

Les Éclipsées runs until May 9, Mon to Sat (9am to 5pm daily), at AFKL, 15 Lorong Gurney, KL. Free entry upon RSVP.

This article first appeared on Apr 28, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.