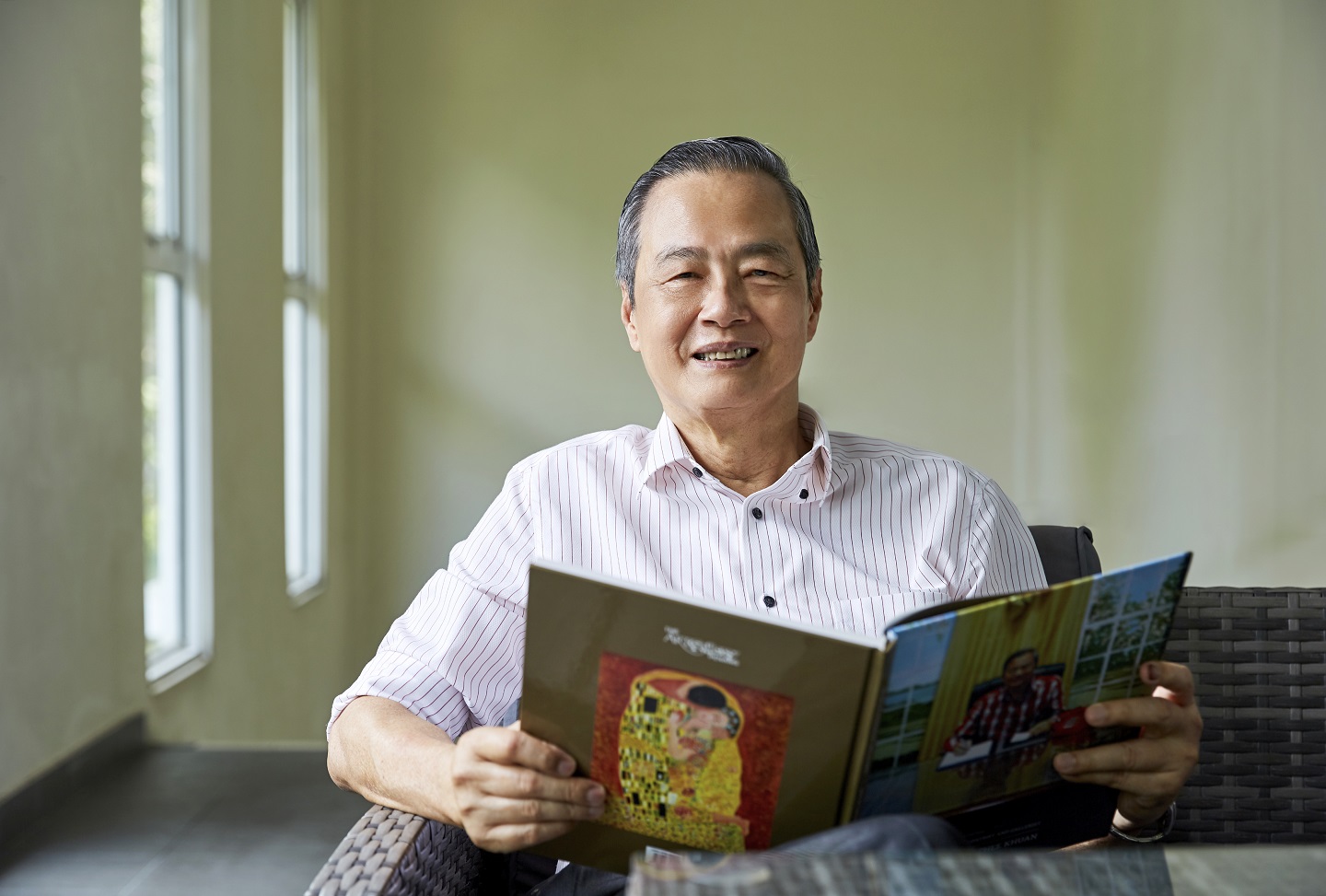

Tan has been an avid collector since 1981 when he moved to Penang (Photo: SooPhye)

Datuk Dr Tan Chee Khuan makes no bones about things that are intimate or personal. He is confessional, the way one imagines a patient would be with his psychiatrist, lowering his volume a notch when he speaks, then grinning as his words hit home.

“I’m a Superman — I can do multiple things at the same time. Okay, I suffer from cyclothymic personality — somebody who is full of energy and active all the time. If it gets worse, you become manic. I am a bit manic. When I love something, I buy a lot of it.

“People think all psychiatrists are mad. We’re only half mad ... I’ve retired from everything except psychiatry. I’ve also retired from women. I’m not interested in women. How can I be when I have no testosterone hormones because of the injections for my prostate cancer? Also, I can’t perform. It’s okay — I’ve had enough pleasure in my life.”

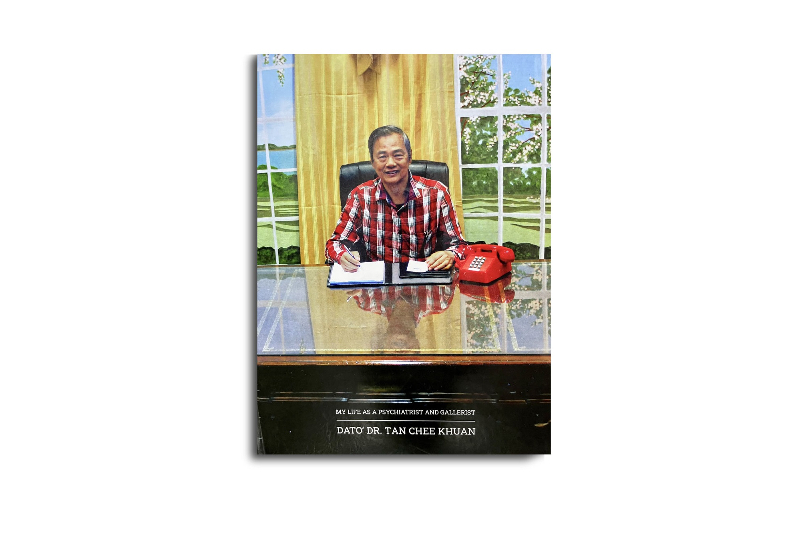

Muar-born Tan was a multi-hyphenate long before it became common for people to employ their skills in several main occupations. The psychiatrist of more than four decades is also an artist, art collector, gallerist, writer and philanthropist. Now he can add autobiographer to his name, with the self-published My Life as a Psychiatrist and Gallerist set for release on March 5.

There is no stopping him once he sets his mind on something. He started writing the book in September 2020, after his cancer diagnosis. The disease recurred in March 2021 and he had further treatment. He is now in remission.

“I planned the whole thing and typed out the articles with a Pitman typewriter. Most of the pictures are reproduced from articles I had written for different magazines. I just ‘vandalised’ them, cut them out and put them in the book. The original photos are all gone.”

“Imagine he did this when he was supposed to be recovering from robotic radical prostatectomy,” says his daughter, Ee Lene, who took over The Art Gallery, which Tan set up in Penang in 1989 with his late wife Siau Bian, after he retired from art dealing six years ago. Obviously, the duo is comfortable bantering with each other.

Her parent has his reasons for writing an autobiography. “I thought I might have something interesting to say, like how I managed to qualify for medicine the backdoor way because of a scholarship,” that enabled him to jump the waiting list for medicine at the University of Malaya (UM) in 1968.

_s1a8546a.jpg

The Sultan Ismail Johor scholarship was among those awarded to non-Malays all over the country to “pacify” the Malaysian Chinese Association after it attempted to start a university — Merdeka University — was rejected by the cabinet, writes Tan, who will be 75 this year.

Atypical of a grandparent who wants to leave something for posterity, he says My Life is “to syiok sendiri, to give myself a thrill, a sense of achievement. People must remember me for what I am lah: I am very impulsive”.

But, seriously, the book was to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his wife’s passing — Siau Bian died in November 2001 — and his 40th year in Penang. It was meant to come out two years ago but was held back due to personal reasons.

There is plenty to tell, starting with scraping through into medicine as the last of 108 students. “My STPM result was the worst among my classmates. If not for the scholarship, I would have become a science teacher and my life would have been totally different today.”

Did writing come easily for him? In reply, Tan snaps two fingers. He sees his biggest achievement as combining art and psychiatry, a rare mix, and thinks he is probably one of the oldest psychiatrists still practising — at Lam Wah Ee Hospital, Penang. When LWE was founded in 1983, he was invited to be one of its eight pioneer consultants.

“I intend to continue working until I drop dead or become incapacitated. I am living two lives in one lifetime — as a psychiatrist and an artist, writer and publisher.”

Why psychiatry? He explains how while training to be an orthopaedic surgeon in Melaka after his housemanship, he noticed that patients were treated in a very impersonal manner. “They were just statistics. But those with cancer needed counselling. Those who had lost limbs needed someone to talk to. Relatives had lots of questions. But doctors didn’t have time to entertain questions because they were so busy.”

He decided he could not just work with patients without talking to them and the only “sensible career” was to become a psychiatrist. He asked to be seconded to UM to study psychiatry. Once that was done, he ran his own clinic in Penang before joining LWE, where he set up a private psychiatric unit — “the first and only such unit in Malaysia”.

Tan scoffs at the notion that psychiatrists only see patients with mental problems. “We deal with marital and sexual issues and everything that can cause people stress.” Art is his buffer against falling prey to that. “After the patient leaves, it’s over. I don’t take the problem home. I go back and look at my beautiful paintings and I feel happy.”

316288785_585774250215281_5170356550903947479_n.jpg

What he has amassed would lift the heart of any collector, especially treasured paintings by the “pioneers of Malaysian art” that he bought cheaply in the 1980s, before their creators gained fame. A Christie’s Singapore invitation to give a talk on that topic was “recognition of my status as an expert on the pioneers”. He was an adviser to the Masterpiece Fine Art Auction House in Malaysia and Singapore until it shuttered during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Tan wrote volumes about local artists he became friends with and published books on their work. Passionate and prolific, he has brought out about 70 books and catalogues on medicine, psychiatry and mostly art.

The Art Gallery, which held about 15 exhibitions a year in its prime, was his main source of income, he confides. “It’s definitely more lucrative than psychiatry. That’s important because I am a compulsive buyer of paintings. I identified the pioneer artists and invested in their work from the 1980s. Later, I put them up for auction or sold them for a good profit.”

This collector also loves opals, fossils and crystals. “I don’t buy [just] one. I buy 50, 100 [pieces]. The house is full of these and I get joy from everything.”

He declares that he is rich in assets, not money. But now, “I am not allowed to buy a single painting”.

“If he buys any more, I won’t run the gallery,” Ee Lene interjects. “I take so long to pitch and make a sale. Then he comes back with 20 paintings.”

“Threats, threats, all the time,” her dad adds, as an aside.

Ee Lene notices that cyclothymia also makes him spend unnecessarily.

“If money is no issue, why not?” he quips.

“He doesn’t check his accounts,” she retorts.

“I buy paintings, then worry whether I have money for them later. When in need, God will provide. Somehow or other, my wife would sell something and it was enough to cover, always,” Tan recalls.

“I used to go to auctions. When people saw me, they were scared. They knew if I wanted a painting, I would bid all the way up. If I want it, I want it.”

lavender-field.jpg

He remembers seeing the late Pak Zain (Zain Azahari Zainal Abidin) sitting at the front at one auction. “He looked back at me and I looked at him. I waved to him and he smiled. Then I put my paddle down. So, he was happy. I couldn’t fight him. That was a painting by Abdullah Ariff. We used to have one of the biggest collections of his work.”

Tan has been an avid collector since 1981 when he moved to Penang. His first purchase was two Salvador Dali sculptures, Cisne Elephant (Swan Elephant) and Gala. They were about RM2,300 each but he only had cash for one. So he offered to sell one piece to a lawyer friend, at cost. Luckily, she did not buy it and he managed to borrow money for the second Dali. Now the sculptures are worth a small fortune and Tan is glad Ee Lene and her brother Chien Li can have one each.

Sizing up his collection, he says it is not possible to sell all that he owns in his lifetime. Probably not in Ee Lene’s too. As such, he has been donating works to state institutions and non-profit organisations.

As of December 2020, Tan had given 432 paintings valued at an estimated RM1.7 million to the permanent collection of the Penang State Art Gallery, of which he is deputy chairman. Among them are masterpieces by Chuah Thean Teng, Yong Mun Sen, Hossein Enas, Khaw Sia and Abdullah Ariff. He has also donated pieces to the Universiti Sains Malaysia gallery.

An artist himself — Smart Phone Addiction even during the kiss (with apologies to Gustav Klimt) is on the back cover of My Life — Tan has sold about half of the 100 paintings he has done. The Art Gallery (theartgallerypg.com) will exhibit 40 of his works from March 5 to 19. Proceeds from sales of the book and art pieces will go to the Penang Home for the Infirm and Aged.

What is remarkable about his taking up the brush is the fact that he is colourblind; the combination of red and green gives him distorted colours. “He can see blue perfectly, that’s why he loves opals and things closest to that colour,” explains Ee Lene, who told him which parts were green in Klimt’s The Kiss.

Tan says the condition does not hold him back because he was born with it; his mother was a recessive carrier. “People ask, how do I appreciate beautiful women, how do I paint? I don’t see the difference.”

What he has always seen clearly, and admired from young, is mum’s pastel painting of a still life with coconuts, which she displayed at home. “I believe my love for art was inherited from or influenced by her.”

His mother died early last year at the age of 97 and, who knows, there could be a link between longevity and genes. “I thought, well, I will live until 97 lah.”

my-life-as-a-psychiatrist-and-gallerist1.jpg

He multitasks in art too. As oil dries very slowly, he does several pieces at the same time. Ee Lene puts that down to impatience — “He wants everything to be finished fast” — but Tan likens what he does to “an assembly of paintings. That’s why the colours get mixed up”.

Working through the night — be it painting, researching or writing — is the norm for him. He has bought thousands of books on art and artists and now boasts a fantastic library. But he is slowly giving away books too. “I need to declutter. Ee Lene says my house is like a pigsty.”

“I say I don’t know what to do with your things,” she pips in.

Does Tan want to say anything in particular through his art? “No, it has no social message, except for beauty. I enjoy street art and prefer murals to graffiti, which is just defacing walls.

“I think contemporary art is here to stay, but it wasn’t invented recently. The first such artist [in Malaysia] was Lee Joo For. You see his paintings; they are all fantastic.”

Ee Lene admits that running The Art Gallery has its ups and downs, such as the lukewarm response to certain exhibitions. “We’re lucky dad chose a simple name that pops up when visitors to Penang do a search.”

She started working with him nine years ago, after studying counselling psychology and serving a stint at LWE. “After mum died, I went back to study and he closed the gallery in 2001. In 2014, some artists asked him to revive it. In between those years, people could call and come in to view works.”

Death is a subject that has been on Tan’s mind from long ago. “I’m not scared of death; everyone must die sooner or later. Fearing it does not make your life better. So why not enjoy yourself? Have a good holiday and then die lah.”

That is one of the reasons holidays have long been a tradition for the entire family. A visit to Japan — Tan loves sakura blooms — and Vietnam are on their calendar this year, the latter because his two grandchildren have not been.

A marathon runner before, he keeps fit by going around Penang’s Youth Park and Botanical Garden. When he turned 60, he and his children made it up to Mount Kinabalu. And he marked that achievement with a painting, which the National Visual Art Gallery bought for its permanent collection.

“Cancer has not stopped me. The only thing is that I have to go for injections every three months. Zero testosterone means no hormone to feed the cancer.”

It also means zero interest in women. But many other things keep this multitasker busy and happy, like sitting back in his office after a patient leaves and letting his eyes wander to the beautiful artworks that adorn its walls.

This article first appeared on Feb 6, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.