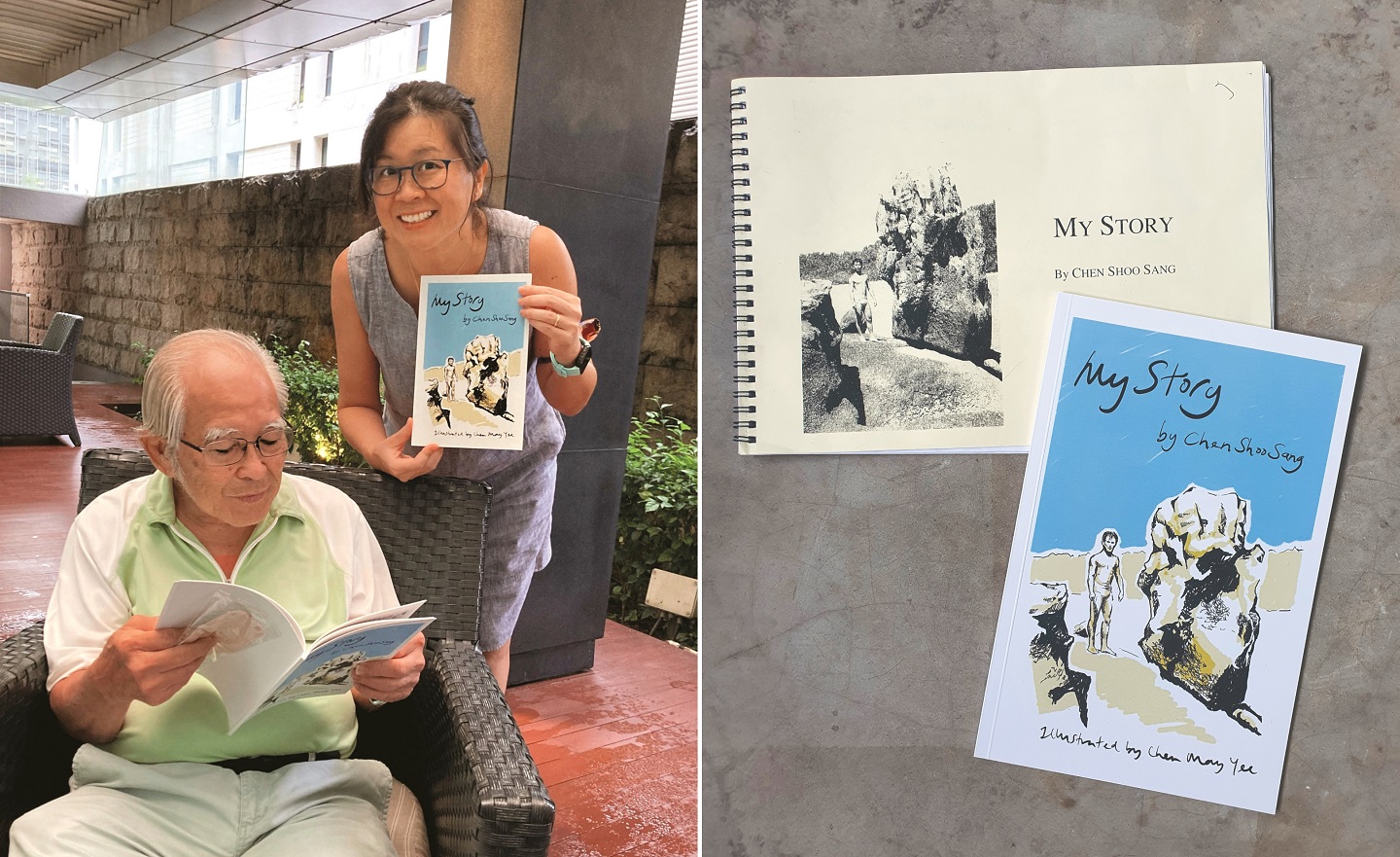

My Story author Chen Shoo Sang and illustrator May Yee, who says ‘there are no superfluous words’ in her father’s writing (All photos: Chen May Yee)

What a man of few words would never have voiced verbally came out in a sparkling stream of prose when he sat down to write. Surprised by his outpouring, the family of Chen Shoo Sang lost no time collating his thoughts in a book.

Thus, Chen’s My Story — written for “my own amusement and for posterity [and which] only family members may read” — was printed and distributed at his 70th birthday banquet in 2010.

After the buzz, the book was put aside and a decade rolled by.

When the pandemic crept in two years ago, Chen May Yee brought it out again and added illustrations to the personal account of her father’s life. There is a backstory to how the book began, she recounts, why the graphics came in and what My Story means to her family.

The elder Chen had said it many times: “I want to write about my past, my family, what happened to my father and why he came to Malaya from China.” But he never got around to it.

In 2010, May Yee remembers, the family suggested that as he would be turning 70 in September, it might be a good time to start on his book. They knew he was going to throw a banquet, but had no inkling what he would come up with for the memoir.

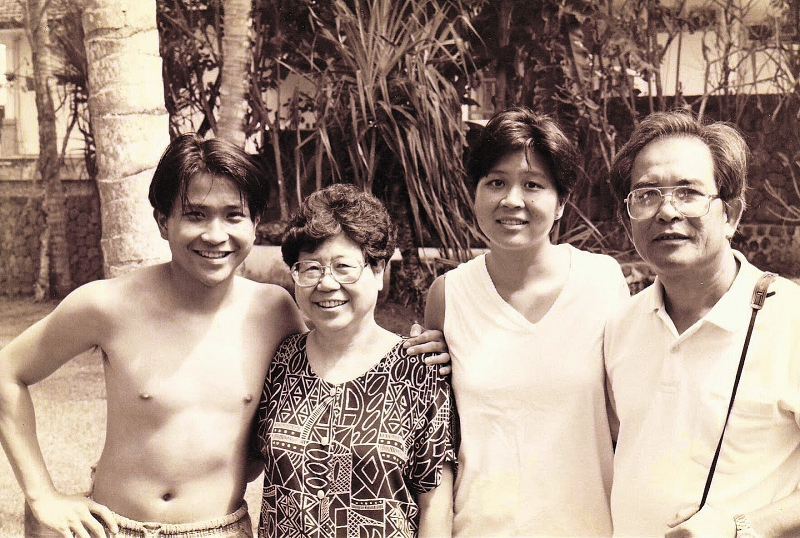

Weeks before the celebration, Chen started emailing them his story. “He would type it out and email us the word document every week, chapter by chapter. I was living in the US then, but my brother [Tien Yue] and our mother [the late Datin Paduka Chen Mun Kuen, director of Royal Selangor] were here.”

3-chen-family_2019_11.jpg

Amazement turned to delight as the chapters stacked up. “My father is a very quiet guy, he doesn’t say much. He’s quite reserved. We were really amazed because we hadn’t seen this kind of [sharing] from him before,” says May Yee.

What they saw was a concise writer with a strong voice, an eye for detail and a surprising sense of humour.

May Yee, who has 20 years of journalism experience in Malaysia, the US and Singapore, found it “a joy to edit someone with a really strong voice who is concise and funny too. There are no superfluous words; he has a point to make and something to say. I’m not saying this because he’s my father. It is just good writing. Obviously, he remembered a great many anecdotes”.

Chen happily handed out My Story, printed in landscape format, A4 size, at his birthday dinner. He insisted on calling it that, “the right decision because we may not all be famous or rich but everybody has a story to tell”, adds May Yee, who flew back with a daughter to surprise him at the celebration.

“People came up and he signed every copy of the book for them. His signature is quite a flourish, so that was fun. His siblings — my father is the seventh of 13 children — were just sitting there and absorbed reading it. The writing is really sparkling.”

Then the years passed and Covid struck. Stuck at home and climbing the wall, she rediscovered watercolours she had done as a teenager and started painting again.

By chance, she came upon Jillian Tamaki’s comic titled Junban in The New Yorker, adapted from unpublished papers written by her grandfather, who died in 1993. George Takakazu Tamaki grew up on a small farm by the Fraser River in Sunbury, British Columbia, where his fisher family seemed set to live forever. Then Japan bombed Pearl Harbour, altering the course of his life.

The comic was the trigger that got May Yee thinking: Wouldn’t it be a great project for her teenaged daughters — who like art and were doing a lot of illustrations online then — to do and get to know their grandfather better? She could also see a wider context for the project.

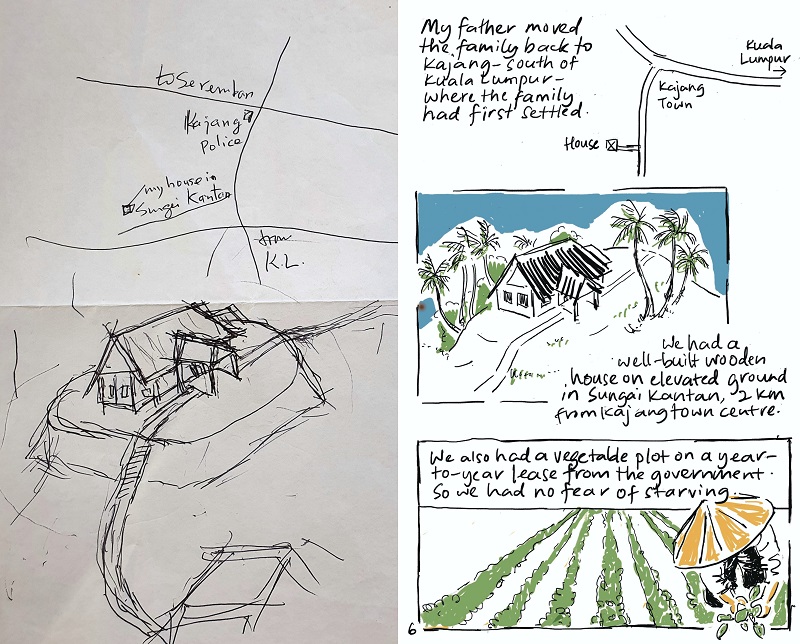

my_story_by_chen_shoo_sang_and_chen_may_yee_1.jpg

“In this country, history is being rewritten all the time for political expediency. I think we have stories we need to tell, especially the Merdeka generation who have seen so much and were there for those big events in the nation’s past. They can tell us what life was like then and write their personal histories so we know. Otherwise, it’s all going to be lost, especially as that generation is now in their 80s and 90s.

“At an age when people’s memories are fading, it is more important than ever to put down what they remember — for them and also for posterity.”

Often, people think of their parents and grandparents as just that, with no idea of what they were like before they became so, or what they are like outside of the family. Family members should be recognised as people in their own right, with their own histories and achievements, she thinks.

May Yee envisioned the fun her girls would have reading grandpa’s memoir and turning it into a graphic book using Procreate, a digital illustration app they had become adept at using during the lockdowns.

She found some pictures of Kota Bharu in the 1940s — Chen’s birthplace — picked one and approached the younger of the two, saying, “Hey, you can start the first page with this.” Instead of enthusiasm, the teen said: “Why don’t you draw it?”

So she did, early in 2021, with the girls teaching her how to use the software. An intuitive artist who likes her brush and paint, she took a long time to figure out how to draw the illustrations and combine them with dad’s text, which she wrote out by hand. Working from home — May Yee is Asia-Pacific director at Wunderman Thompson Intelligence — she could only do one page at a time during the weekends.

It was basically a fun family effort that gave everyone something to work on and connect with each other during the pandemic, she remembers. Her older daughter, who is going to art college, gave suggestions on what was missing (such as a plate of food for one drawing), details that added a lot to the artwork. Her brother posed for pictures she needed of Chen’s father, as did his daughter for a student at a school their grandfather taught in. Tien Yue’s wife Shen Yi took the shots and sent them to May Yee, who worked off them. A neighbour’s 13-year-old was the schoolboy sitting at a table that she drew.

my_story_by_chen_shoo_sang_and_chen_may_yee_2.jpg

“I followed the original text but cut it down to make it work with pictures. There’s very minor editing. Every time there was a page, we shared it with my father. He would be so happy, and then the next one would come. When I printed the whole thing, he said, ‘Wait, what is this? But I wrote another book.’”

When she finished last May, family members and friends she had shared the project with on Facebook began asking when the book would be out and could they get a copy.

Chen did not think people would be interested in his story when asked whether it was okay to publish it. Not that his children are rushing to do so.

“I am still finessing the book. The point is not when we are going to publish it. The point is to talk to your family members and find out what their lives were like and you will be richer for it. I want to focus more on finding out these stories and having the family involved in the conversation. I’ll be quite happy to hear people’s advice on how to start a conversation with their parents.”

One could begin with really simple questions you don’t ask on a daily basis, she suggests. What did you want to be as a child? What games did you play? What was school like at that time? Tell us about your childhood.

“It’s nice for the older folks to be asked because, often, when you get older, you become invisible. Often, too, we leave these questions until too late and the story is gone.”

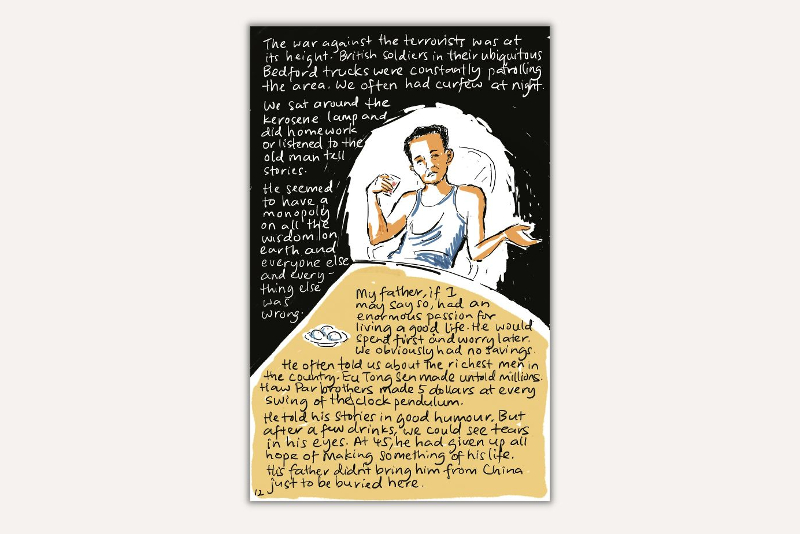

What May Yee finds special about Chen’s book are the chapters on his own father, a mystery to her generation because he died at 51. “What we remember is his mother, a very strong woman who tried to keep the family together after her husband’s death. Clearly, his father loomed larger than life even though he didn’t live to a ripe old age.”

They knew Grandpa was a Chinese schoolteacher and, at some point, the principal of some small Chinese schools around the country. They also knew the family moved around a lot because of his work and lived in Kajang, Puchong, Sungei Buloh, Kuala Selangor and Kuala Kubu Baru. What surprised them was that he was a kind of pillar of society.

2-chen_holiday_mid-90s.jpg

“After World War II, my grandfather went back to his school in Kajang and basically rebuilt it on his own. He was the sole teacher, except for my grandmother, who taught alongside him. The children had lost three years of education because of the war, and parents would stand by the window and look in so they could listen as well. My father has this detail in the book: ‘When the school added a second class, my mother became the other teacher. I doubt she was ever paid’.”

Another thing that jumps out is how Chen pays tribute to various people in his life, from teachers who helped him make the transition from Chinese to English school to the education chief of the Federal Capital of KL. With exam results in hand — “Form 5 was already a great thing. Now I needed a job to survive.” — he went to see Davidson, who had been the headmaster of Kajang High School, hoping for a position as a school clerk because his father was a police clerk before becoming a teacher. The burly Scot made a phone call that got him into Form Six instead.

May Yee is struck by how fate intervenes at various points in one’s life. “All these people who, through what might have been small acts for them, really changed the trajectory of a young person’s life. Things could have gone in different directions for my father and we wouldn’t be here today. He and my mother wouldn’t have got married — they never really talked about how they met and got together — and he would have done something else. If he hadn’t written it down, we wouldn’t have known any of this.”

Mum, who passed away in 2019, was the extrovert who talked to everyone and penned May Yee letters every other day when she was abroad. Her father wrote only once, after she graduated from journalism school in 1994 and sought their advice on whether to stay on in the US or return to Kuala Lumpur and take up a job with AFP (which she eventually did). He faxed her a handwritten note, of which she can only remember one line: “The road to the top of the mountain is long and winding.”

She says: “What? Stay or go home? That was how little he said. He is always quietly supportive and very proud of what we did. He is very much the old-fashioned Chinese father who is quietly present. Clearly, he noticed things, because he has lots of stories.”

After Form Six, Chen joined the civil service and became a tax collector for the Inland Revenue Department. Then he joined Turquand, Youngs & Co, which became Ernst & Young (now called EY). Following that, he went into various businesses before setting up his own small property development company.

After May Yee completed her illustrations for My Story, her daughter reread it and commented: Kung Kung is really a good writer. “I said, ‘You know, he is.’ It’s quite delightful, if I do say so myself.”

The phrase “if I may say so” crops up in Chen’s book. Like father like daughter?

This article first appeared on June 13, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.