Supported by Astro and the Creador Foundation, the fund — of which Chong is one of 11 beneficiaries this year — is inspired by the late theatre director’s pioneering work in celebrating original Malaysian creativity (All photos: Anthony Alexander Chong)

It was while setting up the interview with deaf activist Dr Anthony Alexander Chong that it occurred how much we take for granted, and how mortifyingly unaware we are about the daily minutiae that can be difficult for people who are hearing-impaired. Chong is exceptionally gracious about it all, but the effect of that initial exchange is permanently seared in our collective consciousness: While we may acknowledge that the world can be a difficult place for the differently-abled, we really have no idea what some of their day-to-day challenges are.

In fact, Chong’s own activism work would not have been further highlighted if not for the Krishen Jit Fund, which is aimed at providing deserving arts practitioners with monetary aid to pursue projects in the arts. Supported by Astro and the Creador Foundation, the fund — of which Chong is one of 11 beneficiaries this year — is inspired by the late theatre director’s pioneering work in celebrating original Malaysian creativity in as varied and alternative ways as possible.

Chong will be using the funds he has received to run a Malaysian Sign Language, or Bahasa Isyarat Malaysia workshop for deaf participants to develop BIM literature in as many forms as possible, such as storytelling, poetry, translated poem, visual vernacular, drama or folktales. The idea is to shape a new culture for the community as well as contribute to building a body of BIM literature. The final work will be recorded for an online performance.

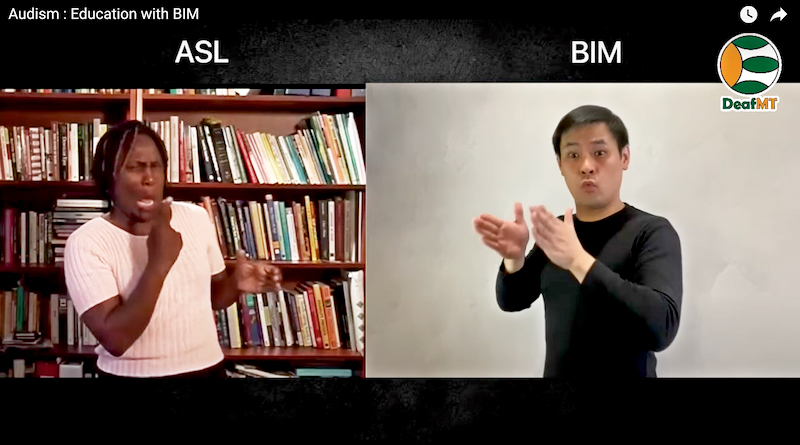

His grant trains the spotlight on the lingua franca used by the deaf community in Malaysia. Kod Tangan Bahasa Malaysia (KTBM) is a communicative method recognised by the government and the Ministry of Education for use in aiding teachers to teach Bahasa Malaysia to deaf students in formal educational settings. It is not itself a language but a signed form of oral Malay adapted from American Sign Language (ASL), with the addition of grammatical signs representing affixation of nouns and verbs. BIM, on the other hand, is the official sign language recognised by the Malaysian government and used to communicate with the deaf community, including on official broadcasts.

fb_img_1574405101599.jpg

“BIM is a language and has its own grammar and structure,” Chong explains. “Like ASL, BSL (British Sign Language) and other sign languages, it does not represent Malay or English or any other spoken languages. Many people have misunderstood that our language is ‘sign language’. It is not. The term ’sign language’ is general, like ‘language’. KTBM is a communication system for the deaf to communicate Bahasa Malaysia using their hands instead of using their mouth to speak. So, when we use KTBM, we are expected to sign every Malay word, include its affixes, to fulfil Malay grammar.”

Although officially recognised today, BIM was actually created by deaf students in dorms who were prohibited from signing anything to each other — they developed their own sords (sign words) to communicate. In the 1970s, American professor Frances Parsons came up with the Total Communications model to better prepare differently-abled children for further education. In 1976, she met with the then education minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who subsequently introduced legislation that obliged schools in Malaysia to adopt Parsons’ method.

“Even though many deaf students started studying under the KTBM system at school, they could not do it well, therefore they shifted to BIM, which is often used by the deaf community. After that, they forgot about KTBM and continued communicating in BIM with their peers. BIM is important for us to communicate our needs, feelings and opinions on a daily basis,” Chong adds.

This is something he understands personally. Born deaf, he attended public school and started learning KTBM when he started primary school. “I was lucky that I learnt some Malay before learning KTBM,” he recalls. “Many of my friends struggled to understand KTBM and Malay. It seemed like we were expected to acquire Malay through KTBM, which was difficult as many of us were not familiar with KTBM sords and Malay words, plus it affected our learning process.”

Chong joined BIM courses after completing his secondary school education, and when it was discontinued, taught it to others for 10 years. Playing an active part in the deaf community, he became increasingly aware of the unique linguistic discrimination that they faced. “Many deaf people think that their language is sign language, KTBM or ASL, when the fact is that they are actually communicating in BIM all the time. The majority of the deaf community have zero knowledge or understanding of BIM, and if they don’t understand what it is, then how would they be able to fight for their linguistic rights?”

screenshot_2021-12-01_at_8.23.57_am.jpg

The objective of his workshops is not just to create a more widespread understanding and appreciation of BIM, but also to push for its application in creative aspects of linguistics like poetry and theatre. He also notes that BIM literature isn’t as popular among the Malaysian deaf community as ASL and BSL literature. There are many reasons for this, ranging from a lack of education in BIM, lack of confidence among those who do know it and lack of recognition on an educational level.

“In Malaysia, BIM is not fully recognised as a language, even though it is acknowledged as a language for the deaf to communicate on a daily basis through the Persons with Disabilities Act. Therefore, BIM is not a subject for deaf people in school. With no formal education, we cannot have a chance to learn subjects like poetry. Because of this, many of us are unable to differentiate between storytelling, poetry and visual vernacular,” he says.

Even before the workshops are completed and the final product becomes available for viewing, Chong knows what he wants to do next. “We need to secure funds to build a BIM corpus with linguistic description, which will then enable us to conduct BIM courses for the deaf community as well as introduce it as a subject in the primary and secondary syllabus.”

Being able to communicate is one of the most basic of human needs, and it is disappointing that in this day and age, years after we put a man on the moon, the hearing-impaired in our country do not have a unifying language that correctly expresses what it is to be Malaysian. It is high time that they do.

This article first appeared on Dec 6, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.