Kamil and daughter Sarah Merican (Photo: SooPhye)

The signs of a great city are usually observed in its architecture. Situated in the far north on the banks of the Nervión River, the Basque city of Bilbao, Spain — recognised today as a vibrant cultural hub — used to boast a starkly different landscape than it does now. Once dominated by shipbuilding, steel and iron ore manufacturers, it was a key commercial port in the 19th and 20th centuries following the industrial revolution. But by the 1980s, this had all changed. A sudden and uncontrolled influx of cheap foreign labour and violent campaigns by the Basque separatist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna cast a dark cloud over the city as, like many others around the world, it braced for the rapidly approaching 2000s. Bilbao struggled to shed its industrial past, plunging locals into economic decline and poverty. Staggering unemployment rates and urban decay marred the locale’s image, and in a last-ditch attempt to change a dim fate, the city shifted focus to the tourism, culture and service industries.

To pull travellers, plans to erect the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao were conceived in the 1990s, described by director Juan Ignacio Vidarte as a “transformational project”. A competition was held to determine the lead figure, and Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry emerged as the victor, beating out proposals from Arata Isozaki & Associates as well as Coop Himmelb(l)au. His dynamic approach highlighted undulating curves sculpted from titanium, stone and glass, inspired by a fascination with marine life.

When the establishment opened in 1997, Gehry said in an interview with journalist Charlie Rose that his study of fish and their movements while sketching out the museum’s blueprint led to his discovering a whole new “architectural vocabulary”.

Today, the museum draws millions to Bilbao each year. The boom in tourism scooped the city out of its post-industrial dark age, surging the local economy with new jobs and increasing tax revenue. The growth this single institution inspires can still be seen today in the development of new artistic and creative establishments and public spaces. The Bilbao Effect — a phenomenon wherein an area experiences exponential economic and social revitalisation through the construction of iconic architecture — continues to be a principal driving force behind the world’s ever-evolving urban panoramas, particularly in developing zones.

musem.png

Kamil Merican, CEO and founding partner of GDP Architects, has seen first-hand how this has occurred in Kuala Lumpur.

“The post-Merdeka years were some of the best times for KL’s growth. Under Tunku Abdul Rahman, we saw a new interpretation of the city with buildings like Muzium Negara and Parliament House,” he recalls.

The 243 sq km of concrete jungle that nearly two million call home has one of the most recognisable skylines in Southeast Asia. Skyscrapers like the Petronas Twin Towers and Merdeka 118 punctuate the scene, towering over winding lanes where contemporary residences and heritage shoplots sit side by side in a mesmerising mesh of old and new. While roaming the streets, you would likely have come across some of GDP’s own contributions to the urban melting pot, such as Pavilion KL, The Intermark, KL Eco City, Tun Razak Exchange and Perdana Canopy.

Now in its 35th year, the practice is focused on navigating an uncharted post-pandemic age where the digital and tangible are interwoven and lifestyles are more fast-paced than ever.

Sarah Merican, a partner at GDP and Kamil’s daughter, illustrates the ongoing task at hand. “When GDP first started, there were a lot of things to be done in KL. We were in a time of nation-building, constructing airports, train stations and much more. When I entered the profession years later, a lot of those things had already been completed and now we are looking at how to move forward considering new technologies and governments.”

Through generations

oldffice.png

Asked about how he fell in love with architecture, Kamil laughs and proceeds to tell a story fit for the silver screen. “As a boy, I was very mischievous. One time, I was hospitalised after getting into an accident,” he chuckles. “My wardmate was an architect. I was looking at all his sketches and thought, ‘Wow, this is interesting!’ and he was kind enough to tell me more.”

Though he never succeeded in seeking out the man from his fateful childhood encounter, that first spark propelled him through years of schooling and hard work, eventually leading him to set up his own company in 1990. “We started when the country was growing. There were so many things being thrown at us from both the government and the public. We took all the opportunities we could, anything under the sky.”

Through the decades helming GDP and his stint as a lecturer with Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, he realised the country was a goldmine for talent and creativity. Harnessing and uplifting these individuals thus became his mission as a leader, igniting his passion for working with young minds which he believed were the key to a progressive nation.

“I like to be involved in projects like RexKL and Sekeping Kong Heng in Ipoh because I felt like a lot of our old towns were dying. When I see young people doing business, I feel very proud. And many of them really have the knack for it! This new blood has different mindsets, and we should allow for more of these fresh ideas to happen,” he beams.

Kamil’s openness to cross-generational collaboration would become a critical point in setting GDP apart from other practices, especially when Sarah came on board years later. After completing her studies at RMIT University in Australia, she tutored for two years Down Under while co-heading a design studio and practising at Fender Katsalidis Architects in Melbourne. Eventually, she returned home to join GDP.

“Coming back to Malaysia, and working for a parent no less, I felt there were a lot of expectations. But how I treated it was that I first needed to understand what it felt like to work here,” she says.

This drive pushed her to take on the lead position for the design of Zepp KL, which currently stands as one of the top music and events venues in the city.

However, it was in R+ — the research and strategies unit — that Sarah found her niche. “They were already doing some level of research on their own but what I noticed was that the work was not being properly applied to our everyday practice,” she notes.

Under her guidance, the young female-led studio evolved into an essential cog in GDP’s well-oiled machine, generating reports to help architects better tune their blueprints to fit clients’ needs.

meg.png

The most recent example of this is Penang’s The Meg, a high-rise residence and the first project on Andaman Island (the prime reclaimed area of Seri Tanjung Pinang). R+’s quintessential part in this operation started with a casual discussion between Kamil and a friend. “He suggested we do an experiment — get Sarah to conduct a study on what our millennial demographic wanted from the project. And she produced a report, and as architects, we used that brief for the things the community needed, whether it’s bigger sports facilities, more meeting points or a coffee shop on the ground floor where it’s convenient to hail Grab cars from. These were all little points to better align with the people we are designing for.”

When The Meg launched on the market, it received a glowing reception, selling at rarely-seen 100%. Kamil largely attributes this success to Sarah and R+. As younger generations become primary consumers, adjusting designs to suit their needs can be difficult without the input of representatives from those target groups.

“Sometimes, we architects just look at residential projects like, ‘Oh, it’s a two- or three-bedroom layout’ and go straight into it without considering what I call ‘trimmings’ — elements that suit the people we are designing for,” the founder notes.

As time passes and civilisation evolves, architects become interpreters of a time period, translating sociopolitical events into structures that go on to define an era. Sarah speaks on behalf of those who take this as a chance to study mankind and its evolution. “The public and cinema tend to view architects as people who will help them build a beautiful dream home, as just artists with good taste. But we actually juggle many affairs, from politics to land issues and social demands. Everyone deals with these things to varying degrees in their own lives, but for us, it’s an opportunity to look at how communities are shaped.”

For the people

newpus_2.png

“No matter where you look and whether you like it or not, politicians have a part to play in architecture,” Kamil says. “The great ones always have dreams, which might not be solidified yet and in need of a technocrat to put it together. But in all the great cities, such as Paris or KL, all the great moves are enacted by politicians. It’s like shouting — almost as if to say, ‘I was here! Look here!’”

This does not mean that all grand buildings are simply to serve a single leader’s personal agenda (or ego) — they can often be for the good of the people. The dozens of skyscrapers across KL are beacons of hope. However, current development has reached a stage where striking a balance between human wants and needs can have vastly different outcomes. There is a divisiveness that splits society and their views on how cities should be planned, subsequently affecting perceptions on architecture and who actually benefits from it. This is especially prevalent in affluent areas where swanky, intimidating design dictates the sort of crowds that inhabit certain areas, and in the heart of the city, hostile architecture further obstructs the lives of the homeless and underprivileged.

Sarah notes how a version of this occurs at GDP Campus and general Bukit Damansara.

“When people come here, there is a subconscious ‘othering’ that happens because you’re in an expensive area and people think you need to be well-off to be here,” she says, though this is far from how the practice operates. “Design is universal. It should be made accessible to all. At its best, it is democratic and does not discriminate.”

In the company’s eyes, inclusive design inherently touches on all the demands (or, rather, the buzzwords) synonymous with the 21st-century patron, especially sustainability. The hard truth of the matter is that development will always come at the expense of nature, no matter what you do or how hard you try. Replanting secondary forests will never be as good as conserving an existing, primary one and, as Kamil says, we have “X number of sq ft, or even a decreasing amount because of rising ocean levels”.

newpus.png

Instead of approaching the matter with brief notions of being climate-friendly or greenwashing, GDP is focused on creating designs that produce as little waste as possible and can stand the test of time, resulting in projects that are “treated like heirlooms to safekeep and protect”. The firm even predicts that many might revert to methods like cross-ventilation, tackling sustainability through old but tried-and-tested techniques instead of relying on technology to keep pumping out newfangled solutions.

It is tough to hit all the marks though, and among the many reasons Malaysians continue to protest development, the argument that it causes the erasure of historical and cultural landmarks is the most serious.

“For a very long time, people haven’t viewed our heritage as something of value. Only recently have they started the restoration of the Sultan Abdul Samad Building; our railways and much of Chinatown are neglected until new life wants to move into these areas,” laments Kamil.

According to him, dwindling pride in our heritage sites is to blame, and the sense of ownership needed to change this has to be instilled from a young age through meaningful education that prompts one to take ownership and responsibility for the upkeep of their surroundings.

Incorporating motifs and patterns, like those of batik and songket, is arguably the easiest way to honour the nation’s cultures while still creating an innovative future. (“In the office, we’ve even made it a rule to wear batik on Mondays to give the industry a boost,” Kamil shares.)

Still, GDP is open to experimenting with new paths like spatial arrangements that evoke the proportions of traditional houses, channelling the essence of a bygone Malaysia while staying conducive to modern life.

Dreams of a nation

exhi.png

Over the past three decades, GDP has constantly placed community at the core of everything it does. To celebrate its legacy, the firm is holding an exhibition at GDP Campus where visitors will get a glimpse of what went into the past 35 years of building from the ground up. Titled group, design, partnership;, the presentation highlights the projects that mark moments in the company’s portfolio and the country’s history, and most of all, the hundreds of people who made this possible.

Kamil remarks: “People are always curious how a practice of this kind and size could survive the ups and downs over the years while still producing good work. It’s good for them to know we’re made up of Malaysian girls and boys just trying their best to climb to the next level and reach new heights. They’ll see the process, how we invest in technology and the quality of our staff’s lives here.”

To complement the showcase, two talks will also take place. The first will feature a diverse line-up of employees to share the highs and lows of the past three decades and their experiences at GDP, while the second invites the minds behind the campus — Kamil, Ng Seksan, Ng Pek Har and Chee Check Keen — to discuss the various tests they conducted to create something that pushes the envelope. Industry folk, students and alumni are naturally expected to attend, but the organisers hope the public will not be daunted to participate too, as these sessions stand to clarify misconceptions about the profession and strengthen the average person’s appreciation for design.

“Normal people almost never employ architects because they imagine us to be very expensive, even if it’s to design their own home. I think it’s good for the general public to know what it takes to plan and build a project,” Kamil says, a sentiment Sarah echoes by reassuring that the questions posed during these talks will not be overly academic and hard to digest for the average person.

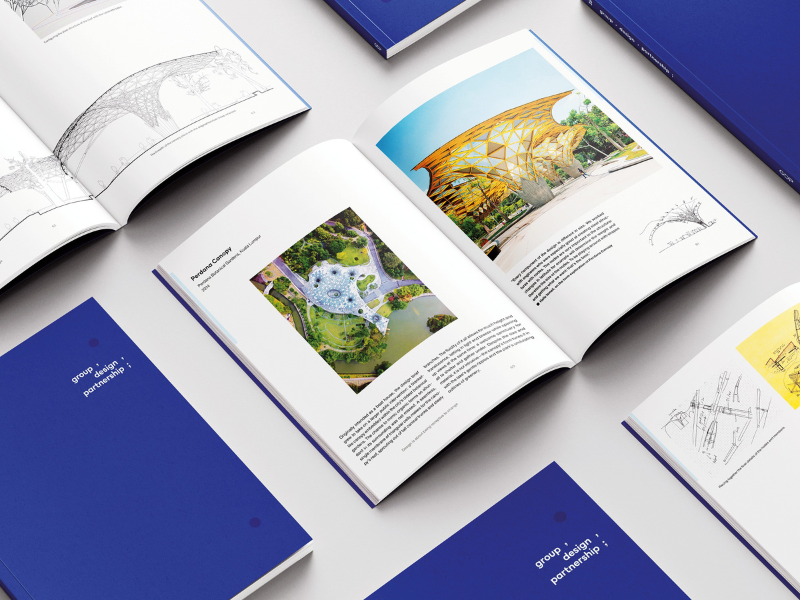

The company is also releasing its first-ever commemorative publication under the same name as the exhibition, comprising in-depth explorations of selected projects and interviews with several personalities who defined GDP over the years, from architects and engineers to secretaries and clients.

books.png

Sarah, who helped write and edit the book, says: “Architecture books usually fall under a few stereotypes — coffee-table, design philosophy and graphics where it’s all pictures and no words. The messaging that comes through with this one is similar to that of the exhibition — everything we do here is a team effort, the product of people coming together to make something happen.”

Kamil agrees, adding that these events are meant to honour the company as a whole, doing away with the idea that landmarks are the product of one sole creator who sits at the top of the pecking order. “With a lot of companies, you only look at the head honcho, the C-suite. Here, we are one people, a group, a partnership. It’s a community that wants to work together in pursuit of a greater Malaysia. Every job in the exhibition, I see the faces of the people who worked on it. I wish other professions and fields, whether it’s in medical or engineering fields or others, would have their own shows too. It’s a celebration of working in Malaysia.”

On a sprawling wall in the hall, a timeline of the country’s evolution is mapped out by key structures designed by GDP and the social, economic and political shifts that occurred during the corresponding years. It looks back on the past three decades of growth, not only within the company but the country as a whole, and how architecture has played a predominant role in the construction of the nation we know and love today.

At a preliminary glance, it may appear like a mere rumination on the past, a hunger for nostalgia. But in the midst of miniature models, diagrams and equipment appears a glimpse of what the future might hold. It is about devotion to purposeful design made by locals for their fellow countrymen, an ode to a striking, kaleidoscopic landscape formed by generations of Malaysian dreams.

'group, design, partnership;' is on show at GDP Campus, Bukit Damansara until Oct 19. For more information, visit gdp35.com.

This article first appeared on Sept 1, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.