Foong holding an intricate cut-out of this year’s zodiac animal (All photos: Low Yen Yeing/ The Edge)

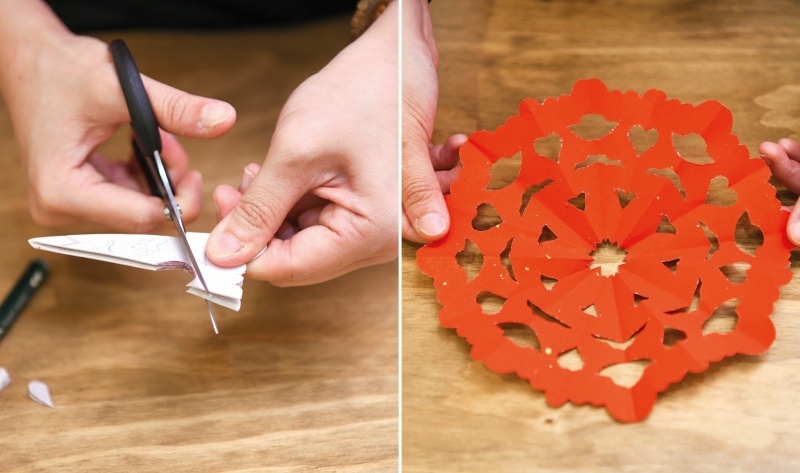

The material is ordinary — square, scarlet, the kind most people would crumple without a second thought. In the hands of Foong Yeng Yeng, however, a flat sheet is coaxed into dimension: arched bodies of leaping carp, sinuous stripes of a tiger and explosions of peonies spring to life with startling animacy. In a motion that feels almost ceremonial, she snips and pares the paper away, letting thin slivers fall to her feet where they gather like snowdrifts. Although her craft begins with something meant to disintegrate and disappear, what emerges from her palm is a majestic being that lasts forever.

Born in Kuala Lumpur, Foong was 13 when she discovered the art of paper-cutting, or jianzhi in Mandarin. While children her age were busy slipping sticky fingers into trays of nian gao, sipping from packet drinks and setting the sky ablaze in vermilion with firecrackers during the festive season, the curious teenager lingered instead over ornate cut-outs pressed against window panes or tucked above doorways that usher luck into the home.

Deciphering basic patterns such as the ingot or mandarin orange came easily, but it was only after she met a seasoned practitioner during her part-time job — selling stationery and calligraphy brushes at a book fair — that her skills in the more sophisticated forms truly sharpened. Before, shaping a spray of plum blossoms, a symbol of resilience, or a lucky magpie was little more than a five-step exercise, assembled as simply as a child might contrive it. Frame each incision with proportion, spacing and depth, however, and the careful arrangement makes the flowers bloom and the birds sing.

The scissors, as Foong admits, were not always her chief implement. She graduated from the Malaysian Institute of Art with a diploma in fine art in 2018, working primarily with acrylic and creating pieces that respond to themes of culture and heritage. Her paintings often unfold through a multiplicity of viewpoints, treating built landscapes not as fixed structures but as vessels of memory and meaning. In works such as A Hundred Blessings, A Hundred Views, timeworn windows, trishaw wheels etched with use and architectural fragments drawn from Nanyang houses dissolve into rhythmic, swirling compositions. Delicate Chinese knot motifs drift across the canvas, binding ideas of harmony and unity. Seen from a child’s eye level, the windows seem to open outward, hinting at varied lives and different hopes of those who lived within.

jianzhi.jpg

“The painting reflects how Malaysia’s cultural richness lies in its plurality,” says Foong. “Every window becomes a blessing, offering its own way of seeing. The gridded patterns come from Nanyang homes in Penang, where my family is from. Yet every time I return, I notice how much has changed, especially the windows. Distinctive in their ornamentation and tied to different eras, many have been left to decay. Our heritage risks disappearing, much like jianzhi, which may lose its warmth and human touch as it is slowly replaced by technology, like laser cutting.”

An opportunity eventually presented itself, allowing these concerns to be explored fully. Selected by the National Art Gallery for a cultural exchange programme in Shanghai, Foong took part in a residency that placed her in museums, workshops and artist networks, expanding exposure and dialogue beyond the studio. During her stay, she unexpectedly renewed her engagement with jianzhi through encounters with master artisans still actively upholding the tradition. China, after all, remains the historical home of the medium, which has continued to evolve since its emergence in the Han dynasty, following the invention of paper by Cai Lun in 105 CE. Long used in totemic contexts to ward off tomb raiders or invoke prosperity, the creative discipline was inscribed on Unesco’s list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

Beyond customs and ceremonies, jianzhi gradually entered the domestic sphere, becoming a familiar presence in households through its close relationship with language. Although regional styles and cutting methods vary widely, the motifs that recur most often are bound by systems of meaning rooted in homophony. The bat (biānfú), for instance, which phonetically echoes the word for blessing (fú), conveys collective hopes for prosperity and well-being.

Floral motifs likewise carry layered associations: the chrysanthemum, long linked to longevity, is referenced in the Han dynasty text Fengsu TongYi, which attributes villagers’ exceptional life expectancy to water flowing over wild chrysanthemums growing on nearby mountainsides. Peonies, too, possess a rich mythological lore. According to legend, when the female emperor Wu Zetian ordered all flowers to bloom out of season, only the peonies refused. They were burnt for their defiance, only to re-emerge the following spring. With jianzhi, such imagery becomes a conduit of cultural memory, transmitting linguistic and historical knowledge across generations.

20260116_peo_foong_yeng_yeng_5_lyy.jpg

Foong’s interpretations are visibly more contemporary, but such modernisation does not diminish its technical grounding or inherited resonance.

“For the Year of the Horse, instead of mighty stallions we’re so accustomed to seeing, I produced a series of cute ponies. Even though some of my work is more current, it still carries flourishing signs such as abundance and good fortune,” she says. The artist notes that distinctions between traditional and modern jianzhi are often legible in formal details, such as the layering of the mane, articulation of the hooves and degree of elaboration in surface patterning. Tinkering with a medium as pliant as paper has allowed her profession to move beyond customary formats, with commissions to embellish perfume bottles and cosmetic cases for brands such as Dior and Hermès.

Asked about the most challenging request she has received, Foong recalls an amusing memory with a smile.

“A potential client once asked to create a serpent motif for the Year of the Snake that would stretch from the gate all the way into the living room. That would have been quite impossible because the paper might tear due to the wind or rain. And that wouldn’t be very ong, I think, so I turned it down.”

Today, jianzhi briefly inhabits our homes, arriving with the Lunar New Year’s rites of reunion and renewal, but its function has never been merely decorative. Transformed yet familiar, it survives by finding its way into new hands.

This article first appeared on Feb 2, 2026 in The Edge Malaysia.