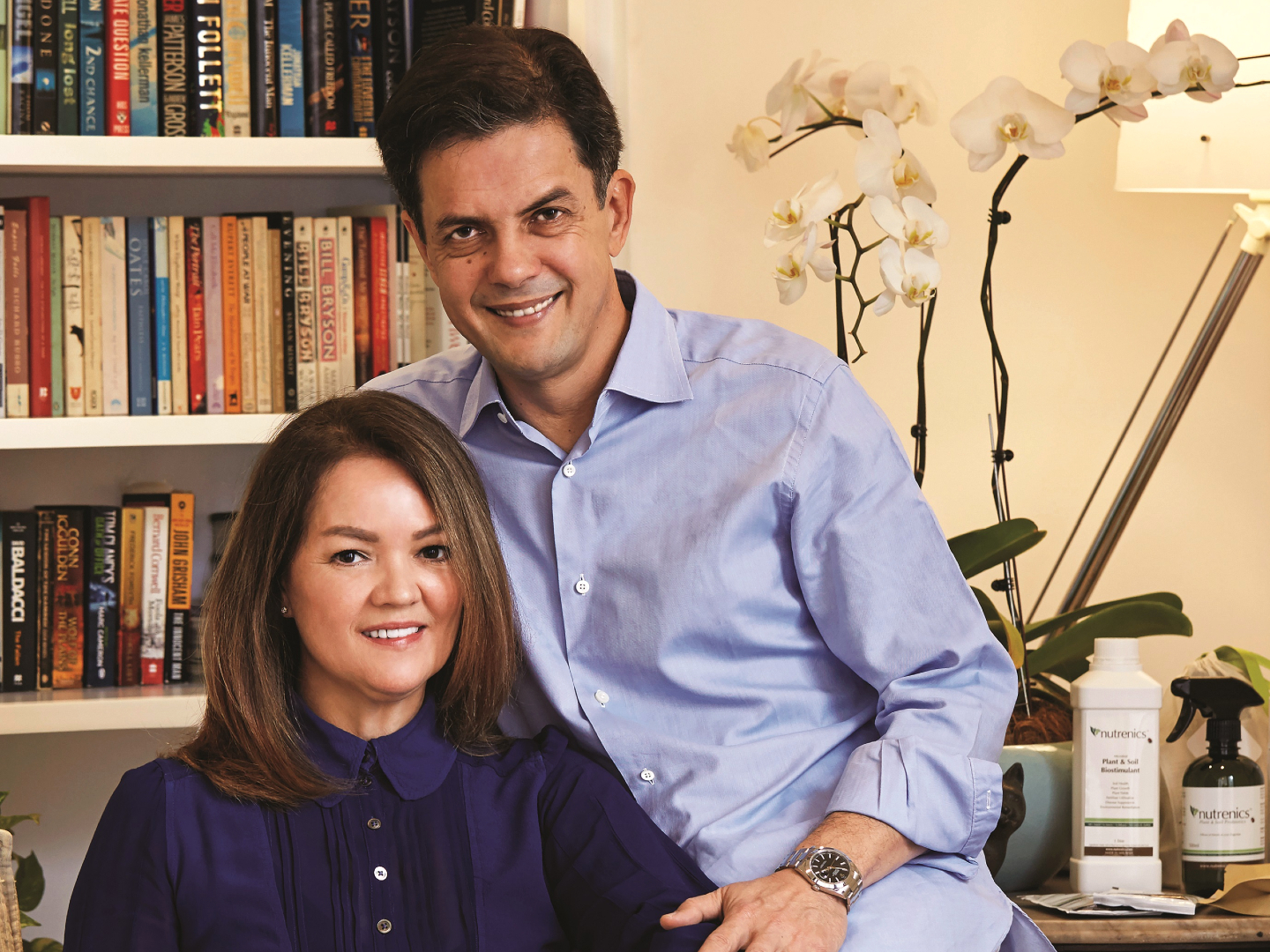

Founders Lorna Dodd and Tunku Johan Mansur (Photo: Soophye)

Fungi or viruses are usually seen in a negative light. “What we don’t realise is that they are very similar to people. Most people are not bad; they can do bad things. Without people, things don’t happen,” says Tunku Johan Mansur.

“It’s the same on a biological level: You have all these bacteria without which plants cannot live. In fact, without bacteria in our gut, we can’t live.”

Microbes, or single-cell bacteria invisible to the naked eye, boost the nutrient content of plants and make them more resistant to disease. But rampant use of pesticides and fungicides in conventional agriculture has killed microbes in soil. The knock-on effect is that soil and water quality suffers and that, in turn, decreases crop yields.

The microorganisms that help plants feed are similar to what we call probiotics in our gut, Johan, a mechanical engineer, explains. When we lack the right probiotics, our body cannot absorb the nutrients in the food we ingest. Processed food, which people are consuming in growing amounts, has been sterilised, boiled, fried and cooked to the extent that the health-giving microbes in them get killed too. “The effects of that are showing in our ecosystem, our immune system and general well-being.”

On another level, the big cost of farming and Malaysia’s huge imports of food — “We pay more for fresh produce here than in the UK” — will cause many problems eventually, he thinks. Food here is also astronomically expensive because distribution and transport costs are high.

For a long time, he and his wife, Lorna Dodd, who has always loved nature, could see there was a problem with food in the country. The question was what they were going to do about it.

_s1a5965a_1.jpg

In 2016, the pair set up Nutrenics to bring a biostimulant to market and help people grow their own food, whether on the balcony, in the garden, as a community or as an enterprise. The idea for the company — which takes its name from a combination of “nutrition” and “ergonomics” — had been germinating since the late 1990s.

Switching to agrarian mode was not easy for Johan. “We’ve become so specialised. I am an engineer — I was taught nothing about food, nothing about biology. It was really hard for me to learn; it took a lot of time.”

The basic idea behind Nutrenics is responsible thinking: When people throw rubbish by the roadside, everybody assumes it is a rubbish pile, and adds to it. “So, are we going to put rubbish everywhere or put food everywhere because what we put out there will grow?” Johan says.

“That’s the wonderful thing about nature”, Lorna adds, “and it is really up to us.”

Johan observes the narrative has always been that if you want healthy food, you grow organic — which is more expensive and produces a smaller yield. This led to the thinking that if you want to feed the world, you have to go chemical.

“It’s not true. You can have healthy food, and more of it, at a cheaper price. Our soil, water, food and health are all inter-related. The simple solution is for more of us to grow our own food. It is our fundamental responsibility to feed ourselves and ask how much control we want to give other people over what we consume.

“If we grow food without all the ‘cides’, we will be healthier and incur less costs, and everything will start to correct itself. That is what we are trying to do. We are not saying we are the only guys doing this. What we’re saying is people have to understand the connections between soil, water, plants, cides, gut health, diseases and hospital bills.”

img_3639-clean.jpg

Being responsible for our own food security will also mean less reliance on imports, Lorna says.

Nutrenics’ plant and soil biostimulant promotes microbial activity to improve soil health and provides nutrients critical for plant growth. The product also boosts fertiliser uptake and suppresses common plant diseases.

A formula for face, hand and skin, available in a spray, is about to be launched. It contains rice bran and the byproduct of beneficial microorganisms. “We have noticed the beneficial effects on animals and humans,” they share.

“Microbes are part of our system. They are the foundation of life. We put them in and let them do what they do. It’s difficult to [promote] this without sounding like some kind of religious zealot, but we have a very sophisticated product and we want people to try it,” says Johan.

When he was in his 20s, he thought, as an engineer, that he could make anything. The years have shown him that what humans can invent fall short of what nature produces.

“Ultimately, we copy a lot from nature. The key word here is the energy efficency that nature has, compared with the technology we have. Our system efficiency is very low compared to that of natural systems. We have a lot to learn [from nature].”

One thing this couple learnt from taking Nutrenics to farmers in Kedah is that traditional methods prevail in agriculture. “We were saying something and everybody else was saying something different. In the end, we thought, why don’t we do it ourselves?”

So they built a farm in Bohor — “in the middle of the Movement Control Order period, it was a nightmare!” — on land that belonged to Johan’s grandfather. Their aim was to show farmers it is possible to grow rice ecologically, without chemicals and presticies. “When plant health is optimised, rice has a balance of carbohydrates, protein and sugar — it’s like a recipe. The plant will do that by itself, unless there is a problem,” Johan notes.

nutrenics_padi.jpg

Basically, what they are saying is: Follow our system and you will get more and better-quality rice, and more income too. “It’s hard to find Malaysian rice with more than 9% protein. Ours has 9.7%,” he adds.

Microbes do the work in their paddy fields, purifying the water in the fields, aerating soil and boosting plant health. There are fish and different creatures on their farm and ducks too — Lorna talks about making salted eggs.

Johan reckons a lot of work is being done around the world now to increase quantity and quality. “Biologists are trying to employ software in agriculture but they don’t know anything about farming. You need to have a bird’s eye view of how to put these things together and that’s what we are trying to do.”

The harvests are in and Johan is trying to find a route to market Nutrenics Padi’s Mulia Fragrant Rice. “Some people think it’s difficult, or we’re crazy.

“We thought if we brought something really good to the market, that is cost-competitive and offers a big benefit, we would quite likely have a support business doing this and we could focus more on expanding cultivation. What we found was nothing like that. There are a number of reasons, systemic reasons ... I don’t want to go into all that.”

Going back to basics, people who have never picked up a trowel often think growing food is hard work. But that is only because, culturally, we do not encourage it, Johan says. Britain is one of the best gardening cities in the world today because of necessity. After the war, there was no food, so everybody grew their own.

In school, children are not taught to appreciate what nature has in store for us. The focus is on technology, not essentials like where our food comes from and how we get it. “We learn things by rote. We have to learn by seeing, smelling and touching.”

Lorna thinks “we have forgotten the smell of good soil. You pick it up, it’s a lovely earthy smell”. She gets a thrill watching something grow — and eating it. “To harvest your own [produce] and eat it there and then or within four hours — it’s incredible. There’s so much joy and satisfaction in that.”

Both offspring of planters, they had different experiences when it came to visiting oil palm, cocoa and rubber estates while growing up. “Of course, when you are a kid, these are the least interesting places you could possibly go to. They all looked the same and were hot, smelly, full of snakes and boring,” Johan says.

“I loved it,” counters Lorna, who remembers kampungs with chickens, lots of vegetation and fruit trees from her childhood days. She also loves horses and works with them.

Johan says his father had wanted to be a soldier but his grandfather, a senior civil servant in charge of agriculture, told him, “We don’t need any more soldiers. We need people to grow food.”

Tunku Mansur Yaacob (1937-1993) did not like the idea very much, but he returned from Cambridge University with a degree in agriculture. He was chairman of Harrisons and Crosfield from 1978 to 1990.

“As a child I used to make fun of him, saying, ‘Agriculture is easy lah. You try engineering, that’s challenging. You guys don’t even have to count.’ The irony is I’m in agriculture now. He’s probably laughing.”

Johan, also a Cambridge graduate, likes design and finding out how things work, and is good in accounting. And engineering, like law and medicine, is something one has to go to university to learn. “I thought that would be good training, so I went into it.”

How he ventured into agriculture is another story.

While looking for new businesses to do in Malaysia in 1998/99, he met, by chance, a guy working on microbes in South Africa. “The field was in its infancy then and he started teaching me about it.”

Lorna says she met Johan when “he was going off all over the world looking for alternative businesses”. They started working on microbes together and that led to Nutrenics.

The pandemic has increased awareness of the need for fresher, better-tasting and healthier food and nudged non-gardeners to set up planters on their balconies or tend greens on any bit of space they have. “People have started growing with enthusiasm and it’s wonderful to see,” says Lorna, who wants to help that happen. The scale does not matter; what does is that people do it, whether they plant basil, rambutan, whole gardens or paddy fields. She is confident “everyone can do it”.

Their plan was always to help people grow more, be it basil, potatoes, durians, mangoes or rice. They have given biostimulants to urban growers such as Kebun Kebun in Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur, because when consumers start to understand more about food, they will do it better.

Johan says: “I keep telling people we don’t have Michelin-star restaurants here not because we can’t get the chefs. It’s because we can’t get the produce. You have to start with that. You have to be able to say, ‘This meat came from here, this lamb came from here, this is organically grown.’

“If we can help people grow better produce, it translates into better food that tastes better. Rice is something we’ve taken on because we spent a million ringgit on our farm to do a lot of things. I’m talking to people now about pepper.”

This article first appeared on Oct 11, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.