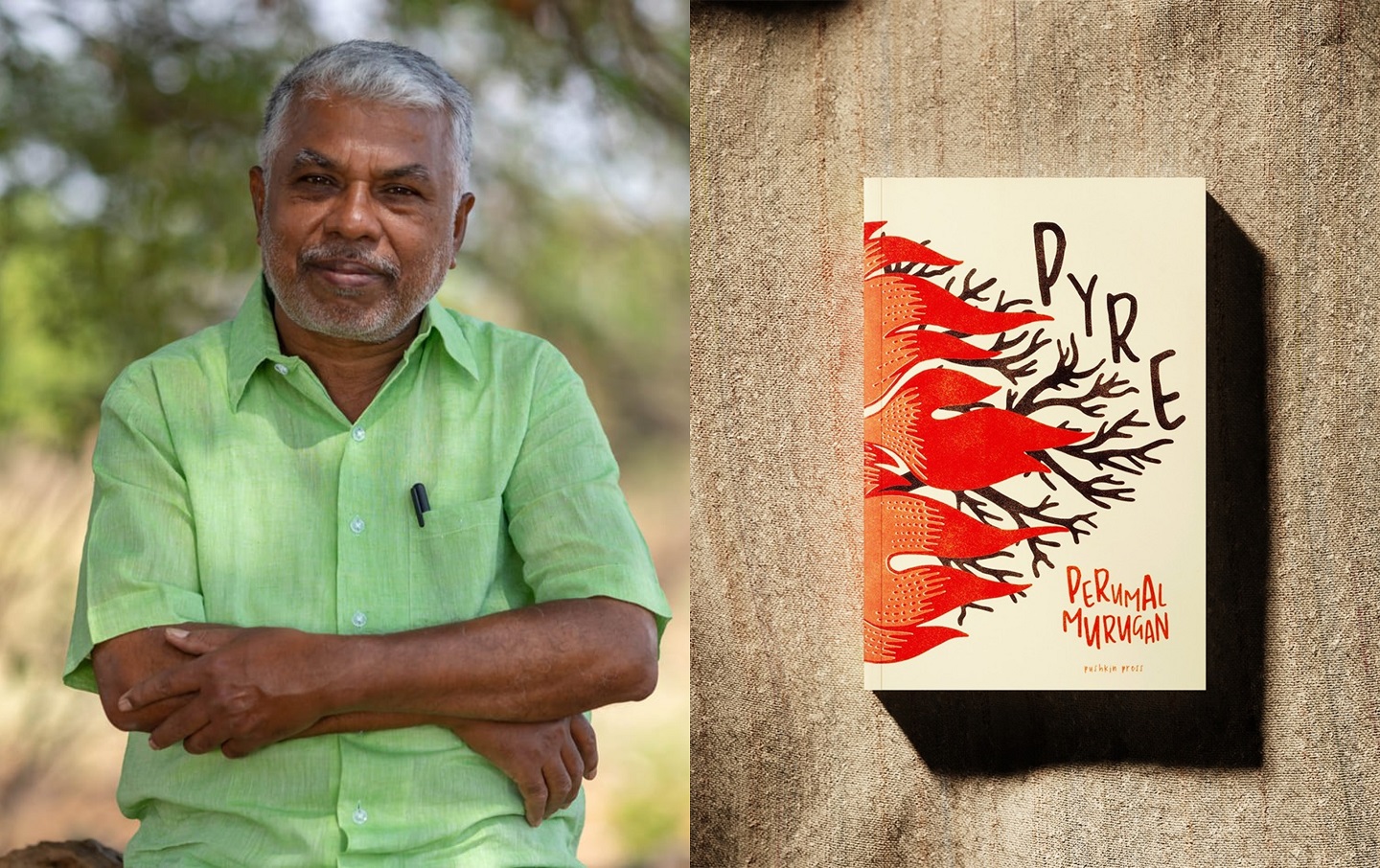

After years of trial and exile, Perumal Murugan confessed, ‘a censor is seated inside me now’ (Photo: Vijayakumar Murugesan; The Booker Prizes)

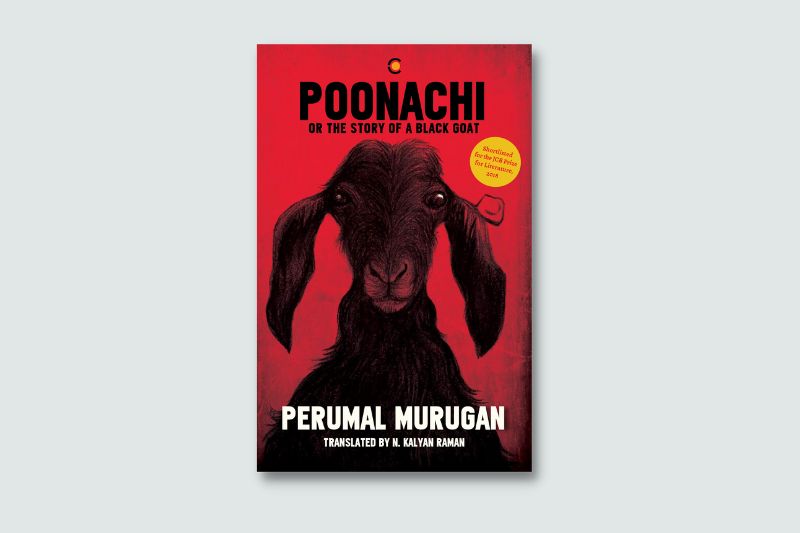

How long can an untold story rest in deep slumber within the dormant seed: I am fearful of writing about humans, even more fearful about writing about Gods. I can write about demons perhaps. I am even used to a bit of the demonic life. I could make it an accompaniment here. Yes, let me write, then, about animals. — Perumal Murugan in Poonachi: Or the Story of a Black Goat

Providence. For all that is required in guile, in mastery of the art that is secrecy and concealment, all finally falls on providence. Nowhere, it would appear, more so than in India — land of determined destinies. Vast: the more remote the region, vicinity, village, the greater the hold of that which remains inescapable — the predestined.

Attributed naturally to, but in reality less the verdict of Gods, it remains the act of constructing a firm and established “social order”; enforcing social codes, imposing social distances, maintaining “purity” and defining, indelibly, that most elemental of relationships — human encounter.

In 2013, R Ilavarasan, a young Dalit man, is found dead, his body lying on a railway track in the northern part of the state of Tamil Nadu. The cause? An inter-caste marriage. Caste violence ensues. The death sentence compressed, as in so many such deaths, in the familiar expressions of “honour” and “shame”.

A court judgment four years later deems Ilavarasan’s death a suicide, though forensic experts claim otherwise. The case inflames public opinion on all sides, but the most lasting epitaph is etched in a dedication to a novel — Pukkuli (Pyre in Tamil).

Once, it was controversy that stalked its author — the redoubtable Perumal Murugan. Following the publication of his novel Madhorubagan (One Part Woman), right wing and orthodox groups, led by members associated with the militarist RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), called for a ban on the book for its “insult”. Threats, a forced exile from his village and a coerced public apology led the author to commit “literary suicide”.

“Author Perumal Murugan has died. He is no god, so he is not going to resurrect himself. Nor does he believe in reincarnation … Please leave him alone. Thanks to everyone.”— was the declaration.

pyre_middle.jpg

A subsequent court case resulted in one of India’s most declarative defences of the writer’s right to expression, delivered by Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, “One of the most cherished rights under our Constitution is to speak one’s mind and write what one thinks … If you do not like a book, throw it away … Let the author be resurrected to what he is best at. Write.”

Perumal Murugan’s response: “I will get up.”

In the years of trial and exile, Perumal Murugan confessed, “a censor is seated inside me now”. His writings were confined principally to poems. “My very existence becomes a threat to anyone I meet,” he would write in a poem, A Strange Beast.

In a curious turn of literary fate following the trial, “resurrection” would shift attention from the now-resolved debacle to the powerfully literary.

Adopting an almost Aesopian incarnation, the novel following resurrection was Poonachi Allathu Oru Vellatin Kathai (Poonachi: Or the Story of a Black Goat). Poonachi might serve as his most intimate book, a commemoration of the idea of land, of animals (in particular, the goat) and his own past. Of goats, he said, “I knew their birthing and growing rhythms as my own.”

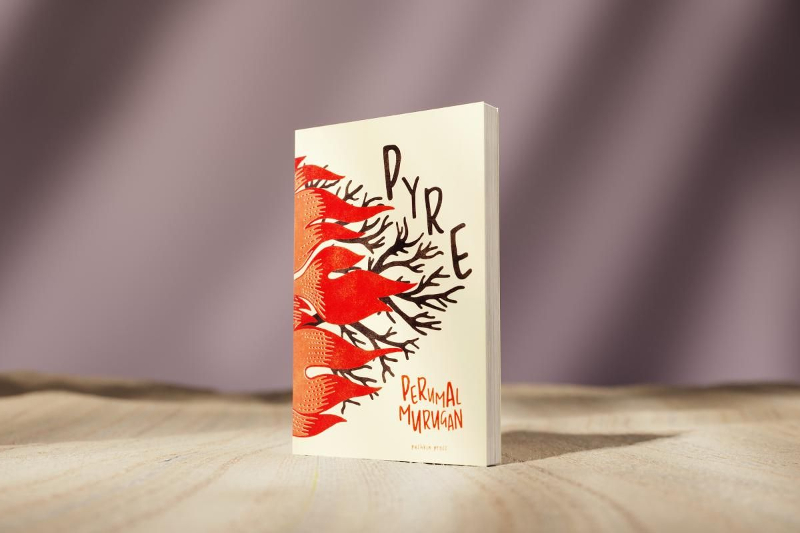

Pyre, now longlisted for the International Booker Prize, settles on enduring themes — caste, submission, rebellion, violence.

Centering on an inter-caste marriage (like Perumal Murugan’s own marriage), it tells of Kumaresan and Saroja, who elope and marry in secret. They escape her village and head to his home, where they hope to conceal her caste and lead a settled life.

poonachi_or_the_story_of_a_black_goat.jpg

The novel commences with their travel, by bus, to Kumaresan’s village. Having already committed this act of social treason, Saroja is surprised upon arriving at the village of the specter of “custom” that still hangs over him. “Step down with your right foot first,” Kumaresan enjoins as they descend from the bus.

Once in the village, Kumaresan’s mother Marayi bemoans the marriage, cursing Saroja and her caste. Villagers gather to insult the new bride and Marayi breaks into a dirge:

“I, his mother, had rejoiced that he would bring me an elephant.

I chirped like a cuckoo that he would bring me a horse.

I danced in joy like a peacock that he would fetch me a cow.

I was thrilled that he would bring me a goat.

But he has unleashed a cat upon us.

Do I catch and leash it or let it wander free?

I could not rejoice at the sight

Of a sturdy wedding tent,

Of invited guests, of the sound of drums,

Of him tying the taali.

That joy, alas, was not mine!”

341323279_1368240814030401_1335303519761938314_n.png

This oppari — an ancient ritual of lamentation, sets the way for the novel’s culmination — the arrangement of a social killing, through fire, animating the novel’s title — Pyre — and the hoary memory of the ritualised burning of brides, sati.

The Booker longlist affirms the growing global stature of India’s non-English language writing. Last year, the award had been given to Tomb of Sand, a meticulously crafted novel in Hindi by Geetanjali Shree. More recently, the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature was awarded to the Hindi writer Vinod Kumar Shukla, a novelist and poet described at once as “strange” and “sublime”.

Perhaps the combination of having written one of the great marvels of the 20th century — Midnight’s Children — then having a fatwa placed on your head, might have afforded Salman Rushdie both the hubris and silliness to declare when compiling an anthology of Indian writing that, “The prose writing created in this period by Indian writers working in English is proving to be a stronger and more important body of work than most of what has been produced in the 18 ‘recognised’ languages of India … and this still burgeoning Indo-Anglian literature represents perhaps the most valuable contribution India has yet made to the world of books”.

This, in a subcontinent that has already produced the likes of Premchand, Sadat Hasan Manto, U R Ananthamurthy, in its “recognised” languages; Perumal Murugan (and his longtime collaborator and publisher, Kannan Sundaram, and his Kalachuvadu Publications). The recent litany of awards may well indicate a long-delayed resurgence in the literature of the community languages of India, and in the crucial realm of literature in translation, in the world.

In Poonachi, a giant bearing a goat kid meets Sami and places the kid in his care with the promise, “This one slid out as the seventh and dropped like a piece of dung. She is truly a miracle, look at her.”

Some years ago, I, by chance, came across Poonachi. Inspired, I have scoured this country since to look for a black goat kid I could bring home for a touch of providence. Not unlike Perumal Murugan — something of a miracle.

This article first appeared on Apr 3, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.