From left: Son Omar Ariff, Tan Sri Kamarul Ariffin Mohamed Yassin and his granddaughter Merissa Alyea (All photos: Low Yen Yeing)

How does a man who “cannot live without trees” ensure that he sees nothing else except green wherever he looks? Well, a deep-seated desire to be surrounded by nature made young Kamarul Ariffin Mohamed Yassin purchase a piece of land in Janda Baik, Pahang, 63 years ago. He had grown up in a small village in Mentakab and worked in Kerdau within the state, and “wanted to have the same environment” after leaving both.

Now living in Kuala Lumpur and turning 89 this Aug 12, Tan Sri Kamarul is grateful there is ample land around his Bukit Tunku home. “From my sitting room, I can see trees.”

Visitors to his four-acre Sentosa Janda Baik will get to see the full picture behind those simple words, understand his affinity with the land, and marvel at what the good earth has brought the former lawyer who served in both the private and public sectors, and his brood, thanks to decades of work put in by his wife Frances. The “architect” behind every landscaped area on the plot, she dug the earth, planted seeds and shoots and watched them grow.

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_72_lyy.jpg

The family’s weekend home for years in Kampung Sum Sum, under an hour’s drive from KL, is now open to those looking for a green getaway. Besides offering accommodation, it serves as a creative arts and events space amidst leafy canopies, flowering plants, fruit trees, ponds and the inviting Sungai Sum Sum.

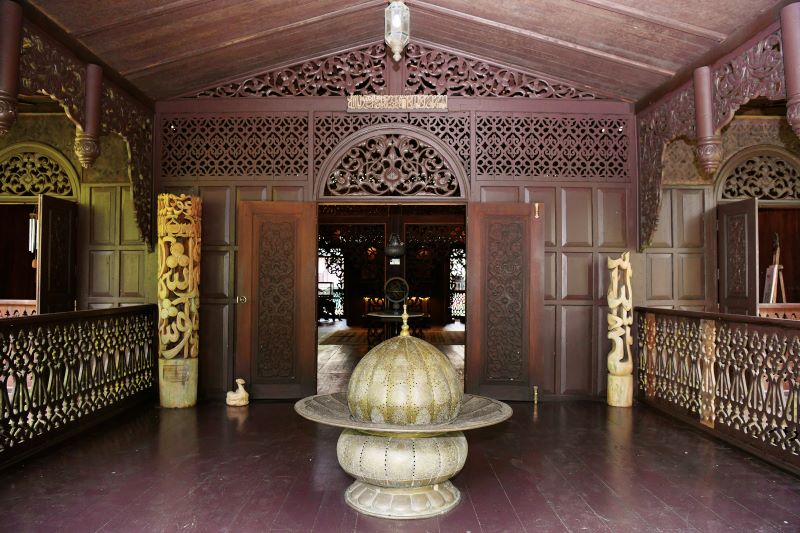

Added attractions at Sentosa Janda Baik would be the three galleries housing countless artefacts, many ancient and priceless, that Kamarul and Frances have accumulated over the decades. The Islamic Gallery is filled with ornate carvings that transport visitors to different times and climes, revealing history, geography and story with every cut.

Grandfather’s Gallery, originally the home of the founder’s forebear in Kerdau, was dismantled and rebuilt here in 2005 to preserve the family history. It houses gardening tools, cooking utensils, furniture, tackle and food boxes used by fishermen, and various gadgets Frances salvaged from the house, probably built between 1895 and 1905. The last anyone stayed there was 1972 and it lay derelict for 33 years.

The White Gallery, originally an abandoned house from Kelantan, was also dismantled and rebuilt here in the 1990s. It now showcases Orang Asli sculptures and those of mother and child in different forms and poses. Kamarul’s son Omar Ariff, who recurated some of his parents’ art collection, says this will be used as a rotational gallery for works by up-and-coming artists.

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_24_lyy.jpg

Call it providence: The seven structures within the property, including the elegantly furnished three-room residence that can accommodate up to 12 guests, might not have materialised if not for an act of “defiance” by its founder.

The plot Kamarul got was originally paddy land and its title stipulated that owners had to plant that crop. For three years, he abided by the condition, digging into his experience of working in his family’s paddy fields from the age of seven.

“Then I looked to my left and right and saw none of my neighbours bothered to do that. At one of my meetings with Razak (Kamarul was former prime minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein’s legal adviser), I asked, ‘Why don’t I plant some fruit trees and build a small house?’”

The first thing Kamarul built was a hut beside the stream so that he could dangle his feet. “One morning, we came and found it had been washed away.”

Razak would later offer him a minister’s post, which he turned down. “I said, ‘Let me continue to be your backroom boy’.”

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_106_lyy.jpg

It was not the first time Kamarul had said no to an offer another man would probably have grabbed. He writes poetry, in Bahasa Malaysia, and Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka asked if it could publish his poems. “But dad being dad, he [declined],” Omar says. As a former chairman of DBP, he did not want people to say it approached him because of that connection.

There was no such encumbrance when it comes to art, which he is keen to share. In the 1980s, the then Sarawak chief minister Tun Abdul Taib Mahmud took Kamarul’s collection of cats to show in the state. That played a part in the eventual birth of the Kuching Cat Museum, in 1993.

Cat sculptures were something he would bring home from his travels for Omar when he was a kid. “They were the easiest to put in one’s pocket. That’s how I ended up with all the cats here,” he explains, with a sweeping gaze at the White Gallery.

Kamarul read law in the UK and joined Shearn, Delamore & Co upon his return, before setting up his own practice, Ariffin & Ooi, in 1965. He was asked to head Bank Bumiputra in 1976 and resigned six years later after seeing it become the biggest bank in Southeast Asia.

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_112_lyy.jpg

Did collecting art come naturally to him?

“Well, I suppose the environment was such,” he says in that slow, sonorous voice that makes you listen. “While studying in England in those days, if I were to stay behind during the winter, I would have had to put coins in the heater. The best place to go was the gallery because it was warm and free.”

He frequented museums, art colleges and institutes and was “carried away” by the works of many famous artists. But, hearing him talk about his student days, one doubts there was money to spare for art.

Kamarul chose legal studies for two reasons: His father was arrested and jailed in 1941 by the British, together with fellow independence fighters Pak Sako (Ishak Haji Muhammad) and Ibrahim Yaakob. After the war in 1945, he was caught, this time by the communists. “That made me want to take up law.”

Barely a year after he left for England, his father died and he had no choice but to work for four years until he passed. “I worked and saved up to [get to] the finish line.” He had jobs at the public library and a restaurant, both in London.

How he landed the latter is a story in itself. In June 1959, desperate for work, Kamarul posted a notice in The Times that read: “Pull rickshaw, drive ox-cart? Young Malay must earn fees for professional final: do anything lawful.”

“I had 300 responses to that,” he recalls, still amazed after all these years. He chose the eatery, simply because it offered board and lodging.

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_108_lyy.jpg

After he was done with books, however, there was not enough for the fare home. So he hitchhiked from Europe across to Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Thailand, and then Malaysia. Unplanned opportunities to visit galleries during those 3½ months, perhaps?

While early exposure nurtured his interest in art, it was Kamarul’s friendship with artists that sealed his love for collecting.

When Omar was born, artist Khalil Ibrahim, a dear friend, gave Kamarul a black-and-white painting of a mother and child. “Since then, I have collected more than 500 sculptures of mother and child, made of all sorts of materials. I’ve been to all the top galleries in the world,” adds the former chairman of the National Art Gallery, who saw it move from place to place before settling into its present building at Jalan Tun Razak.

Coming back to Sentosa Janda Baik, Omar says it has “a bit of nature, a bit of culture and a bit of architecture” for those who come a-calling. There are hornbills, dragonflies and woodpeckers to spot during the day, and the orchestra of frogs, cicadas and other insects come night. Guided gallery tours can be arranged; similarly, groups can book ahead to have lunch or dinner with views of its natural abundance.

This second of three siblings remembers spending school breaks at Janda Baik as a small boy, when the family was not abroad, and cycling and playing with the village kids. “I made friends in the kampung and still know them. We’re considered locals because we’ve been here a long time.”

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_67_lyy.jpg

He also remembers following his dad to antique shops and scouting around wherever they visited, when he would rather go back to the pool and swim. With hindsight, if he had not tagged along, “I don’t think I would have the exposure, the passion for art”. He also appreciates having watched how his parents showed their friends around their holiday home, pointing out happy finds and rare pieces.

“Even though he was a lawyer, my father has always had that artistic soul in him. I don’t think I’ve seen him happier than when he was with artists.”

Mum, on the other hand, grew everything on the land and she would ask often ask what happened to this or that plant. Pointing to a mature clump he helped her grow in 1986, he proclaims that he knows where all the trees are, especially the fruit bearers, from Japanese mangosteen to rambutan, asam jawa, kedondong, ciku and belimbing.

When Covid-19 kept Kamarul and Frances away from Sentosa for two years, Omar worried about moving things around at the property. “I mean, it was not easy because theirs is a labour of love. This whole project you’re seeing here, it’s not about money.

‘’You need to have that foresight, that real vision for it to end up like this. It doesn’t just happen. Like I said, we never had an architect, we’ve never had engineers. This is a family thing and we do a lot of the maintenance work ourselves.”

Still, the property needs to be maintained and it costs a lot to upkeep, with the sprawling gardens, staffing, repairs and new features. Hence, the family’s decision to open it to the public. It is still early days: Besides engaging with those who come to stay or for visits, he will see how things shape up and whether running a homestay is enough to sustain the place.

A photographer-cum-author who has come out with several coffee table books on nature, Omar knows well the beauty of places where it thrives. Human input can add to their attraction.

Pointing to the café near the entrance where guests are served breakfast, he says he sat down to size up what he wanted to add, from walls to new bathrooms to ramps to make the place disabled-friendly. “I’m waiting for the delivery of a special wheelchair to take people up all the stairs so it is open to everybody.”

20230320_pla_sentosa_janda_baik_94_lyy.jpg

Omar’s daughter Merissa Alyea put on hold plans to complete her final year in journalism in the UK after the family started welcoming guests last November because she “developed an interest in Sentosa”. She is on board, handling social media and events.

“She’s got her grandpa’s blood. You know, she started off cleaning the toilets and now runs a lot of the stuff here. I always consider myself a bridge between my father and daughter,” he says, pleased and proud.

Merissa is prepared to dig her hands in the dirt at Sentosa, where things need time to mature. At home on the property — she and her cousins would all cram into the biggest room for merry company during family stays — she is the continuity it needs to bring plans to fruition.

Having strangers on their private weekend home will take some getting used to, but the pair like the idea of people taking away something from the place, be it awareness of an artist or his work, a good night’s sleep, a sense of peace or that feeling of connection with the land.

“The main goal is to have everyone learn something new when they come,” says Omar, who relates to the natural cycle of life on the land. As plants grow, leaves fall and are removed. New shoots spring up and they continue to evolve.

“After a while, it looks after itself. You cut the grass and do a bit of trimming here and there. It’s like a life process.”

Ultimately, he hopes to continue his parents’ legacy and to tell the family’s story through the galleries because “what dad has built deserves to be shared, the aspects of architecture, culture and nature.

“I don’t deny the place needs to be maintained, so we need to [earn] a certain amount for it too.”

With the years of tireless effort this family has invested in Sentosa Janda Baik, anyone who walks through its gate would wish for it to thrive, on and on.

This article first appeared on Apr 24, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.