Yee: I’m really Malaysian, actually, but deeply Sabahan. (Photo: SooPhye)

Ask Yee I-Lann what her art is about and out tumbles words such as power structure, colonisation, nation, history, politics, equitable power, consensus, feminist versus patriarchal, circular economy and cultural tapestry. Be patient; she will slowly cut them into morsels, making each inviting and palatable.

Should you happen to be at the table, Yee may just get up and make for a mat on the floor, tuck her legs under her skirt, then go back to where she left off. This time, if the conversation flows easier, it is probably because you are chatting with each other on a new level.

If this Sabahan artist starts asking what the table means to you, lay it all out. She is no dictator of how others should view that utilitarian object. “I like it when people bring their meanings next to mine, dancing alongside my ideas.”

She and various collaborators worked together at different sites on Borneo Heart Kuala Lumpur, a series of exhibitions, workshops and talks. Focused on finding the way forward, BHKL — a continuation of her first show in her hometown Kota Kinabalu two years ago — uses the tikar (woven mat) and tamu (weekly market) as a platform for community, storytelling and ritual. Co-produced by RogueArt, it opened in March and runs until July.

Beneath the simple concept of tikar and tamu lies an open invitation to share a mat and talk to each other. “Maybe I’ll end up lying in your lap,” says Yee, recalling the way she did whenever she had a fever long ago and her grandmother would place a wet cloth on her forehead, under a ceiling fan. “Somehow, everything melted away. I would fall asleep and be fine.”

What worked then can work again as people from Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak examine how they can look ahead while holding on to their past, especially in a present where contentious issues simmer.

“What can we do to each other to reduce temperatures, bring down the fever if you like, and share a space? That’s the intent, to slow down and celebrate our deep locality. I’m very into that because we work in Malaysia, at our deep local level, neighbour to neighbour, and as a country. The tikar is our base.

“To know us better, you have to learn from the past, which is always present in current times, and as we make our future. I’m always trying to understand things better, like the confusion of everything. Where do you start to unpack that? I feel you have to really start at the beginning, go back into time through multiple timelines, which is what I’ve been doing in my art practice for three decades.”

_s1a2757a.jpg

Where Yee comes from — she returned to KK in 2017 after 25 years in KL — the market goes by different names for different communities. But people flock there to get what they do not have — the rice seller looking for salt from a vendor, who may be in search of brass.

The same exchange happens when “I need the other, someone who is not me. I need new knowledge. I need to learn how to do things differently. I need the gossip of the wider lands so I’m not just in my kampung”.

Market gossip can change an election, she adds, leading the discussion to the power of cultures. “Many underestimate the power of art and culture, [the latter] our point of difference, our way of marking time and expressing philosophies and thinking.” Her interest in how people do that leads her to the mat.

It is not the same as tolerance or putting up with each other. “I need you who are not from me. I need the difference. And I love that. To me, this is a big lesson from our Sabah market — look for someone who’s not you and in that relationship, you will both grow somehow.”

Culture, to Yee, is curiosity. It is about trying to understand why something is the way it is. It is also about pursuing different kinds of knowledge, and understanding the world and our place in it, our caretaker role. Culture is about acknowledging a child’s curiosity and nurturing that into adulthood, away from rote learning, so he can find expression through art, which is powerful and important.

Such thoughts interest and stimulate this artist and keep her from boredom. “I might be tired but I’m never bored.”

Philosophical? No doubt, but such thoughts fire Yee, who studied photography and cinematography and used to work as a production designer. Refusing to do law was the only fight she had ever had with her civil servant father. Mum was a teacher who helped found five schools in Sabah. They met as Colombo Plan students in New Zealand, her home country.

“Between them, we were a very community family. I grew up embedded in KK life, where we knew everyone and everyone knew us.” Half jesting, Yee thinks she has “entered the realm of notoriety”, as a result of artworks that plump archival resources and examine politics, power struggle and, particularly, claiming space and how people get to where they are.

Sabahans care very deeply for their own people and cultures. She likes that they celebrate their differences and are not as fearful of them as, say, folks in KL, where “everything is homogenised and flattened out. You have to be the same, think the same”.

Pride in who they are underscores their desire to be themselves and not succumb to the homogenisation of West Malaysian culture. Unfortunately, historians omit multiple stories, especially those of Bornean Malaysians. “You’re given an official history, one written a certain way and sanctioned a certain way.

lili_siat_didy_ilann-dusun_karaoke_mat.jpg

“We’re not very good at addressing our histories. But our history is fascinating because we’re in the fluid corridor region of the world. On the map, we’re literally geographically and physically at the centre of the Southeast. Do you know that the first figurative art paintings in the world were found in caves in Borneo and Sulawesi? But where is that in our pride of nation?

“Sabahans and Sarawakians are very, very good at being Malaysian. We know what we are. The problem is the Malayans who don’t know that they’re Malayan and claim to be Malaysian. Peninsular Malaysia is 39% of the [country’s] land area; Sabah and Sarawak make up 61%.”

This significant fact is not reflected in the local history syllabus, which talks about Sabah, Sarawak and the formation of the country in one chapter. “We don’t learn Malaysian history, we learn Malayan history,” she laments.

Yee likes reading history and politics, especially the meaning of the latter. “Politics is how you organise your house, right? I’m interested in that and how we got to where we are, and trying to understand power structures.”

Vocal but not aggressive, she hopes, Yee is very clear about who she is. “I’m Sabahan, Bornean, Malaysian and Southeast Asian. I identify with all of that. I’m really Malaysian, actually, but deeply Sabahan.

“My grandmother is Kadazan and she is the only grandparent I really knew. My sense of place and belonging also comes from her. That has nothing to do with a school education — I know exactly where I’m from. We are five siblings and four are in Sabah. My sister longs to be at home but she’s married to an Australian and that is difficult for her. We all know where home is.”

Unfortunately, many have little knowledge of Sabah, leading to simplistic perceptions. There is much to be done in terms of the telling of a more holistic, fairer, more balanced Malaysia. That, in turn, will give Borneans a bigger presence and they can claim their space. Yee uses her art to that end.

“What I try to do is have a strong voice, an opinionated voice, to share my opinion and bring as many people as I can with me. I have so many collaborators, maybe because I’ve spent so long in KL that I have that privilege of being able to understand the city, its spaces and its tribes, the contemporary tribes.

“I want to use my privilege to bring as many people and voices with me as I can, but not in an aggressive way. I know I might come across that way and I apologise for that. I mean it, you know, in a way of passion. I want to reach out and take up space. I want us to enter the consciousness of the wider us, of Malaysia, because it’s not happening.”

In her personal capacity, she does what she can to “bring our storytelling, our views and ways of looking at the world, our philosophies, some of which are very shareable, and use them like a lesson, in a way to claim our part in the nation for this idea of Malaysia that doesn’t really exist — balanced, equitable, fairer for all its bits and corners.”

Using the tikar works for her on many fronts, as an artist, a Sabahan, and a Southeast Asian who exhibits internationally. “I’m always dealing with the Western art canon on how to claim spaces. So I’m claiming spaces in Sabah, Malaysia, Southeast Asia and globally.”

_s1a2759a.jpg

Every ethnic group in the Southeast Asian archipelago had a mat-making tradition and a name for the mat, she notes. “We have 100 names for the mat. To me, that’s a very clear linguistic indication that we did not have tables. Our tables were maybe a pelamin for the sultan, a wedding dais or a dulang for your betel nut.”

Mats are also intergenerational and multilingual, in that they can be read by neighbouring communities, leading to knowledge shared through largely women. In a way, they become a language. Motifs can be read, like emojis, Yee explains.

Tables came in with others, whether it was the Chinese kapitan, the Indian chettiar or the British authorities. It was always the traders, the powers that came in, who began to colonise someone, not with an army of guns but an army of tables.

“Suddenly, you have the desk that brings in an education system, that brings in censors, photography, ethnographic images that measure the shape of your nose and define you.

“With a gun, I shoot you dead. With a table, I tell you who you are, and then your children will learn the same, your children’s children will learn the same.”

Adults and children can learn more about mats and how they play a part in weaving connections on an equal footing from two books by Yee, which will be launched as part of the BHKL programme.

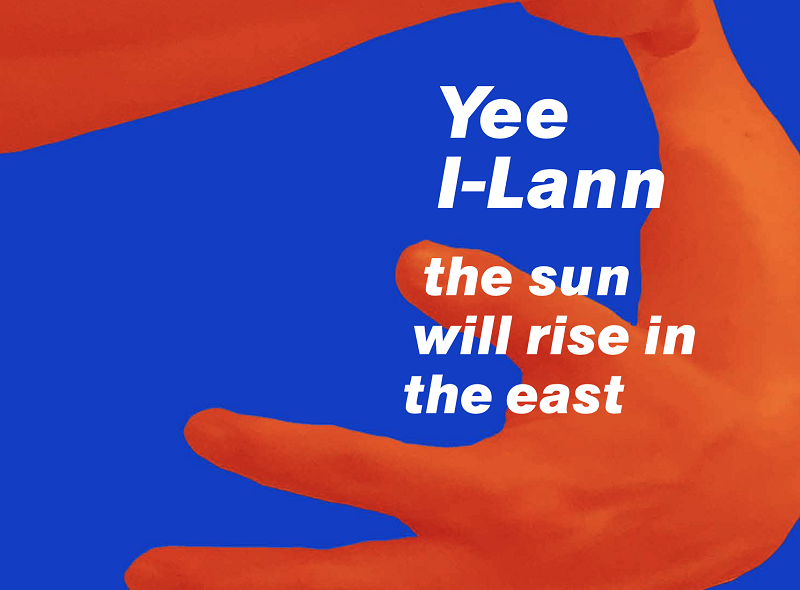

Yee I-Lann: The sun will rise in the east is a 216-page monograph that traces her artistic journey through essays and conversations and photographic documentation of works made from 2011 to 2023. It traverses different geographies and maps, unfolding lines of thinking, and takes the reader on an adventure across languages and philosophies for living.

The book has essays and interviews by Yee, Ray Langenbach, Pauline Fan, Nalini Mohabir, Eriko Kimura, Lucy Davis and Beverly Yong, and conversations with Noraidah Jabarah, Roziah Jalalid, Siat Yanau, Lili Naming, Shahrizan Juin and Julitah Kulinting, as well as 112 pages of colour images.

Yee I-Lann: At the table is the same book, except that it is 80 pages and only has essays and conversations, with black-and-white photos. Both are edited by Beverly Yong, with design by Ming Tung, and published by RogueArt.

They are Yee’s first books and those who follow her work will hope for more. Does this artist known for her digital photocollage and video works intend to paint more?

“I love painting but am not very good at it. I used to have a lot of fun pretend painting,” says the “insecure painter” who hopes to pick up the brush again.

the_sun_will_rise_in_the_east_cover.png

Conversations on the mat

The tikar, or woven mat, represents egalitarian, communal, feminist politics. It is a social architecture that is flat and modular, rather than hierarchical. It is flexible and can afford to be generous. When people join hands to weave mats, they create different stories, visual languages, philosophies, economies, geographies and art histories.

The spirit of community and horizontal knowledge-sharing drive Borneo Heart in Kuala Lumpur (BHKL), which turns on two concepts: the tikar as a collective platform for community, storytelling and ritual; and the tamu (weekly market) as a meeting place for the exchange of goods, stories and ideas.

Through a series of exhibitions that started in January, BHKL looks at how people can create new spaces, aesthetic languages and ideas through conversation and collaboration when they join mats and make use of them for their communities.

Yee I-Lann initiated Borneo Heart in Kota Kinabalu, her first exhibition in her homeland, two years ago to celebrate the community, cultures and knowledge of the indigenous peoples of Sabah, to whom she is indebted. In the same vein, the KL iteration depends on the hospitality and collaboration of art.

Two ongoing BHKL shows have been extended until July 16: Lift the tikar! at Ilham Gallery and Balai Bikin at Rumah Lukis. The first features videos, woven sculpture and tikar works by Yee that draw out ways in which mats, in form and concept, can be a medium for thinking about art, power, language and how we shape society.

Balai Bikin tells three stories about making. It looks at materials, concepts and the collaborative process behind four tikar works or series and how Borneo Heart has unfolded via a network of weavers, filmmakers, dancers, creative producers and friends since its inaugural exhibition. It also follows the progress of Balai Bikin, a project by the weavers of the Pulau Omadal community and Yee to create a community and building a hall in their village, and the challenges they faced.

On July 2, there will be a collaborators’ walkthrough and the launch of Yee’s two books at Ilham Gallery (Levels 3 and 5, Ilham Tower, 8 Lorong Binjai, KL). To register, email [email protected].

Yee I-Lann: The sun will rise in the East' (RM280) and 'Yee I-Lann: At the table' (RM30) will be available from July 4. For pre-orders, call (016) 308 5037 or [email protected].

For details on 'Balai Bikin' at Rumah Lukis (11 Jalan AU5D/4, KL), contact DM @rumah.lukis on Instagram.

This article first appeared on May 29, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.